Hot Towns, Urban Heat Islands

It’s Hotter in the City

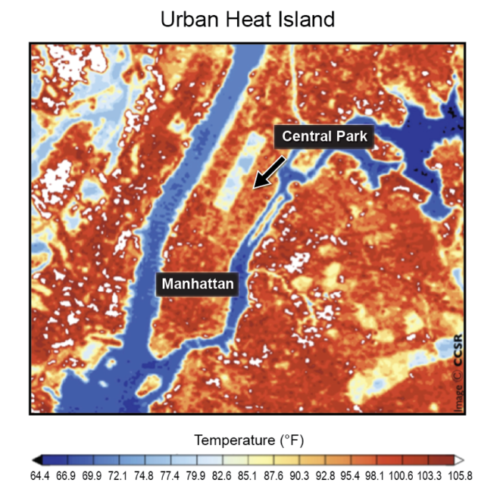

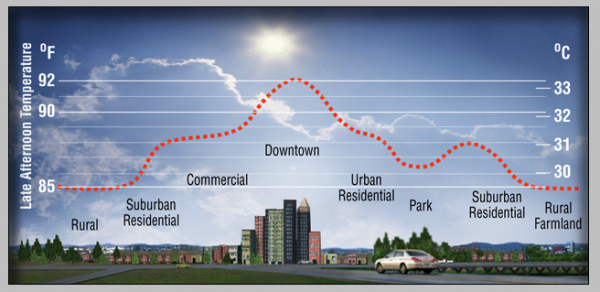

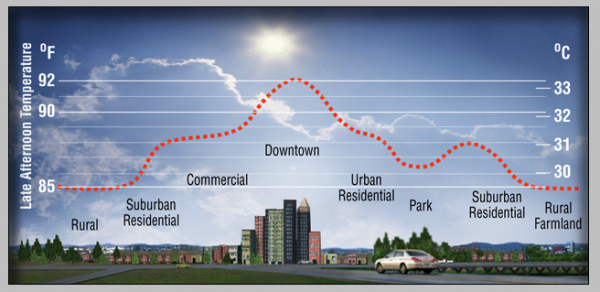

Have you ever noticed on weather reports that cities seem to be hotter than the surrounding areas? That’s a result of the Urban Heat Island (UHI) phenomenon. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, urban areas with 1 million or more residents have a mean annual temperature 1°C to 3°C warmer than their surroundings. At night, the effect is even more pronounced, with city temperatures reaching up to 12°C hotter. With more than half (54 percent) of the world’s population living in urban areas [1] and the trend toward urbanization increasing, UHIs have a significant effect on the way populations experience climate.

How Is the Urban Climate Different?

Urban environments have a high percentage of surface area covered by buildings, streets, and parking lots. These surfaces are generally dark, and water tends to run off quickly. The dark surfaces absorb more infrared (heat) radiation from the sun than lighter rural areas do. As the day goes on, these surfaces radiate the absorbed heat, increasing air temperature well into the night. Also, roofs and paved areas are drier than the soil in rural areas, which limits a cooling effect from water evaporating.

Impacts of Urban Heat Islands

Positive effects of UHIs include a reduced need for heat in winter and a longer plant-growing season. Negative effects include increased energy consumption, higher emissions of air pollutants releasing more greenhouse gases), and impacts on human health [2]. We’ll look at these effects in the following sections.

Energy Consumption and Air Quality

Electrical demand in the United States increases 1.5 percent to 2 percent for every 0.6°C increase in temperature. We know that urban heat islands add 1°C to 3°C to regional temperatures. Thus, a typical urban household uses between 1.5 percent and 6 percent more energy for cooling than a rural household does.

Burning more fossil fuels to generate electricity results in increased emissions of sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, and fine particulate matter. It also contributes to increased ground-level ozone formation and smog.

Health Effects

[tweetthis]Heat was the top cause of weather-related deaths (7,800) in the US, 1999 to 2009.[/tweetthis]

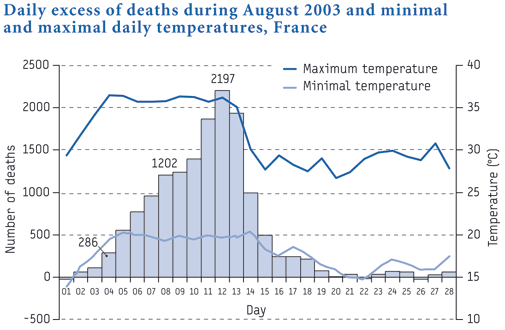

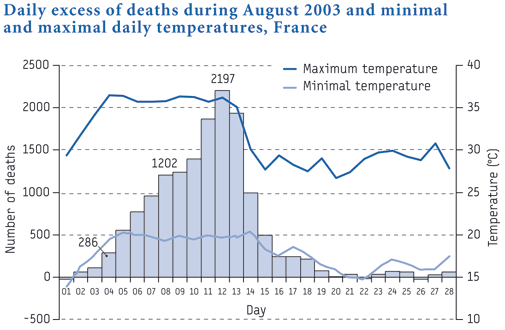

Prolonged high temperatures cause a range of human health problems. They make existing medical conditions worse and can cause rashes, cramps, heat exhaustion, heat stroke, and even death. During extreme heat events, mortality doubles for every 1°C increase in temperature. In hot conditions, an extra 1°C to 3°C degrees due to an UHI can be lethal.

According to the Center for Disease Control (CDC), during extreme heat events—such as the one in Chicago in 1995 that resulted in 650 deaths—infants, the elderly, and homeless or low-income people are most at risk. Heat was the number-one cause of weather-related deaths (approximately 7,800) in the United States from 1999 to 2009 [3].