Relaxed Queen Bees Have More Offspring

Queen bees produce different proteins when they are stressed, and this new discovery could change how we monitor hive conditions.

Farmers, scientists, hobbyists—numerous keepers play a vital role in caring for the bees that make our honey and pollinate plants. However, beekeeping is a difficult process, and keepers often face challenges in maintaining the health and safety of their bee colonies. When troubles such as disease or lack of resources arise, they can cause considerable damage to hive populations.

A series of ongoing projects at the University of British Columbia aim to assist beekeepers in tackling these arduous challenges. In these projects, researchers study the health and environmental impact of honeybees, working to develop a variety of methods to improve them both.

In one remarkable study, scientists at UBC investigated a new way to prevent one of the most persistent causes of hive population loss. This new research could lead to vast improvements in sustaining bee colonies for years to come—and it all starts with helping the bee at the very top of the ladder.

All hail the queen bee

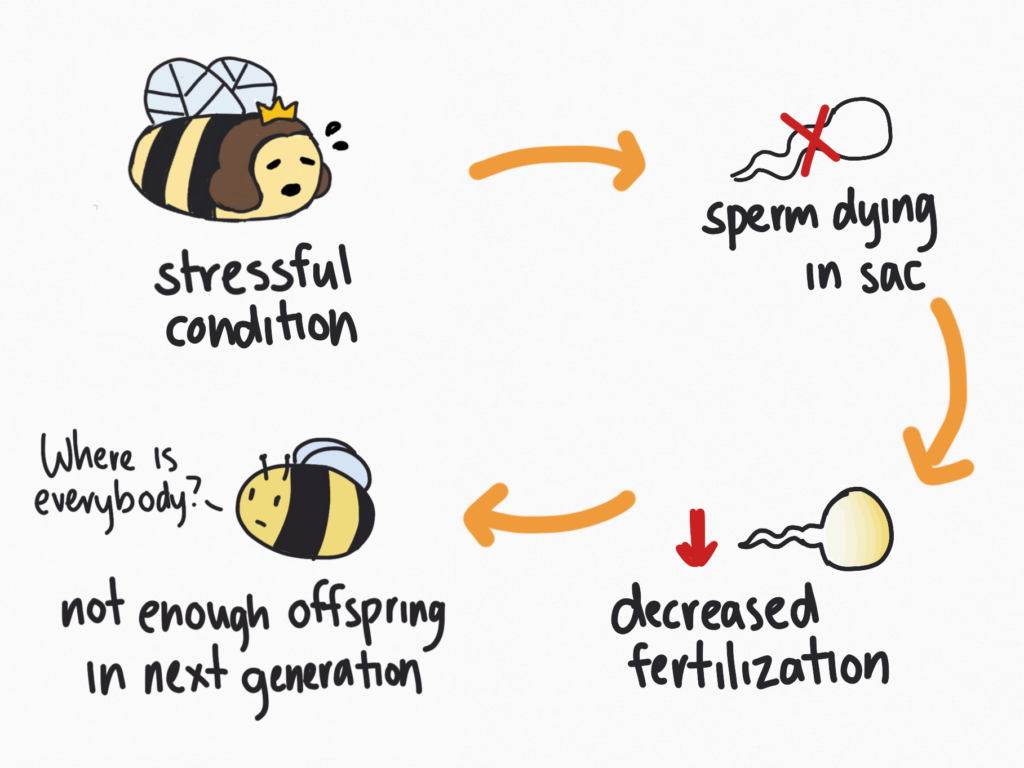

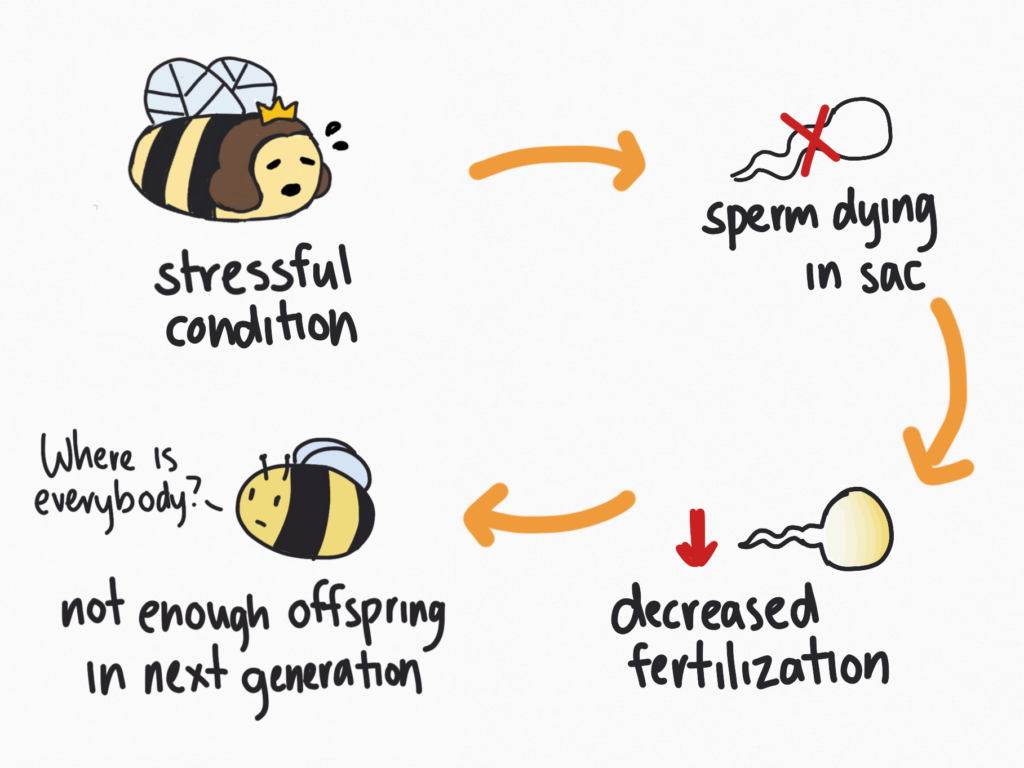

The role of a queen bee is to lay most—if not all—of the eggs for a colony. The queen first mates with male drone bees, storing their sperm in a special sac within her body. These sperm then go on to fertilize the queen’s eggs over her lifetime, after which she continuously lays new offspring—sometimes up to 2,000 new bees every day! In this way, the queen bee ensures the coming of future generations, and the colony’s continuous livelihood resides in her power.

However, despite this paramount position, the queen’s power still remains fallible. Taxing conditions in the surrounding environment, such as undesirable temperatures, can place undue stress on a queen bee. This stress can cause sperm to die in her sac before they have a chance to fertilize.

This phenomenon, known as queen failure, hinders the birth of offspring and causes immense problems for the colony’s survival. In fact, according to numerous beekeepers surveyed in North America, it is one of the most reported causes of dwindling hive populations. Finding a way to prevent queen failure would secure the preservation of countless colonies—vastly aiding both bees and beekeepers alike.

This was the goal of a team of researchers at UBC, who set out to discover more about the processes involving queen failure. Through an intensive study, they made several significant findings that could soon unlock a potential solution.

A test fit for royalty

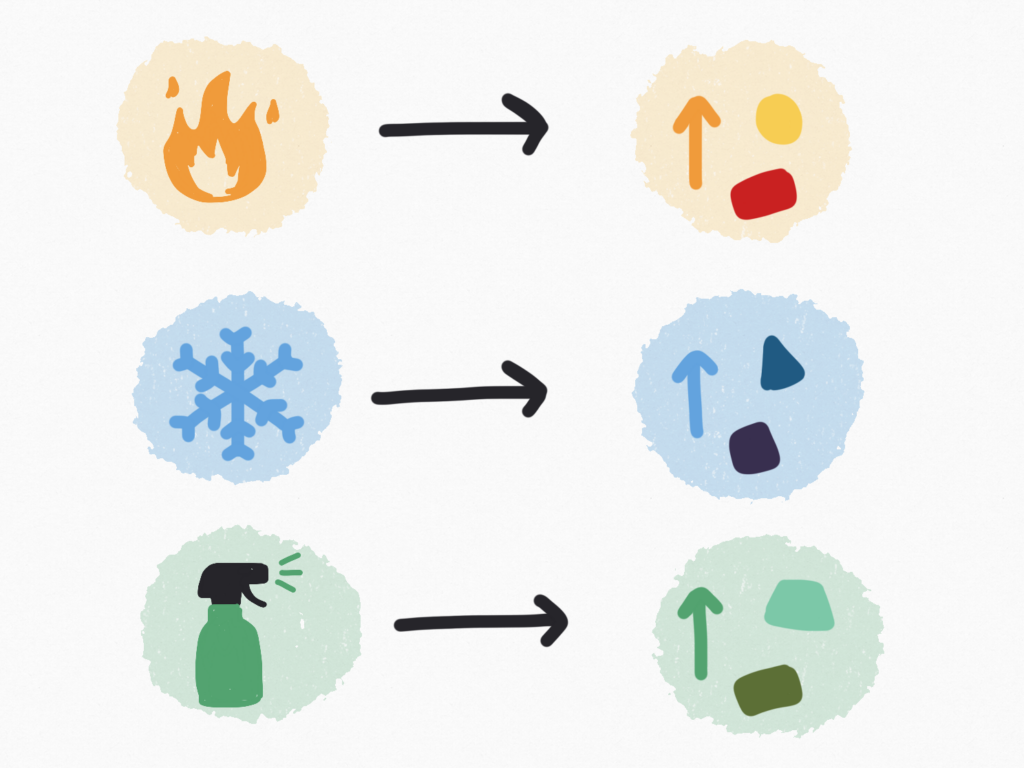

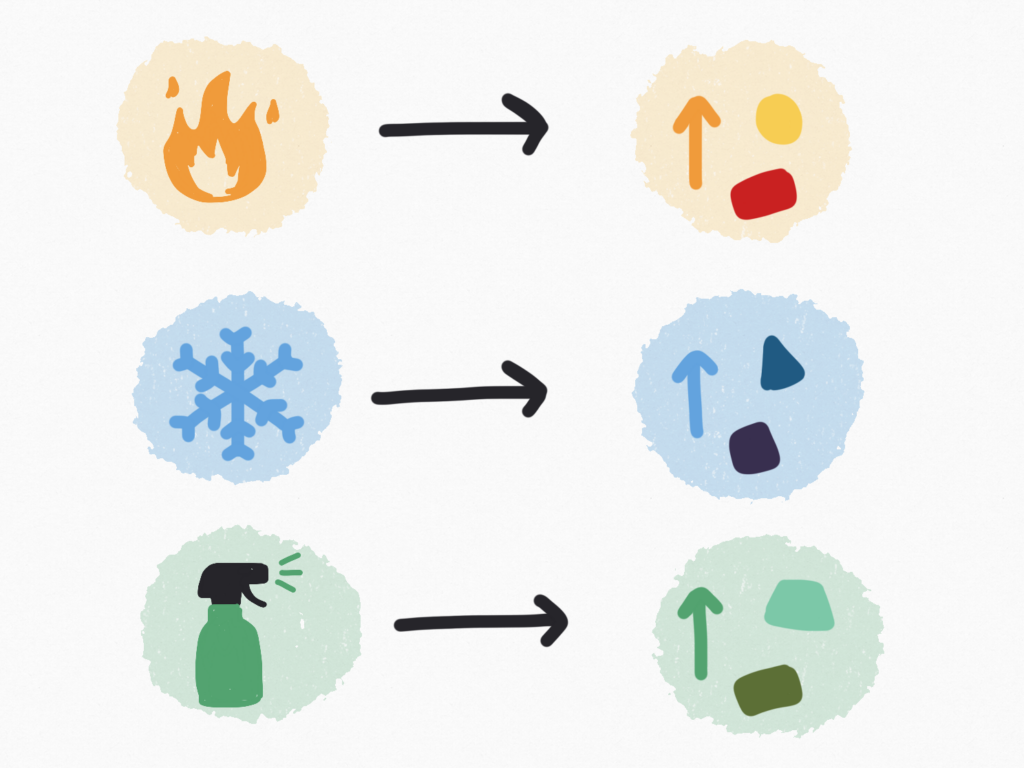

One of the obstacles in preventing queen failure lies in trying to pinpoint its root cause. As previously stated, one contributing factor is undesirable temperatures; this applies to both those which are too high or too low. An additional stressor is exposure to pesticides, which can accumulate in hive products such as beeswax.

However, out of these conditions—heat, cold, pesticide exposure—it is hard to tell exactly which one of the three leads to queen failure in a given situation. This is especially difficult when transporting new bees to keepers, as they often go through many temperature fluctuations in transit.

An ideal solution would be a diagnostic test for failed queen bees, which could accurately determine the exact cause behind each one’s plight. In their study, the researchers at UBC found a way to develop such a test—through harnessing the potential of proteins.

Protein productivity

In animals, proteins help to form organs and tissues, as well as perform essential tasks for the body. In order to keep up these functions, new proteins are created by the body each day. More remarkably, however, the amounts of protein produced can differ based on the surrounding conditions. When a change in environment occurs, the body can create more of a certain type of protein, while creating less of another.

With this knowledge in mind, researchers decided to test how protein production might change in queen bees under stressful circumstances—more specifically, those that bring about queen failure. In order to do so, they first mimicked hot and cold environments by placing one group of queen bees into an incubator at 40°C, and then placing another group into one at 4°C. They also mimicked chemical exposure by anesthetizing yet another group of queen bees with a mix of different pesticides. (All queen bees were unharmed in the process of these experiments.)

Afterwards, researchers used tools to analyze the protein production levels of these three groups. They found that compared to normal queen bees, stressed queens produced significantly higher levels of certain proteins. Moreover, the researchers found out that each different stressor caused different types of proteins to increase. This means that just by looking at protein production, one could determine exactly which situation affected a failed queen.

This discovery paves the way for a diagnostic test to potentially be developed based on protein level. Once a test is released, keepers can be more easily informed of the specific conditions causing queen failure—and can then take measures to improve these conditions and prevent failure from happening again.

Better for bees

Although this experiment points to bright results, there’s still more research to be done before a proper test can be developed. Suggestions for further analysis include determining the threshold level of stress for increased protein production, and whether the findings apply to queen bees outside of North America. Once new research gets underway, however, it hopefully won’t be long before a solution is on the horizon.

As for now, you can do your part for bees by buying organic whenever you can, avoiding the use of pesticides in your gardens, and planting a variety of pollinator-friendly flowers. If you live in an urban area, try volunteering at a local park or community garden—research shows that these can be great spaces for pollinators to thrive. Through these steps, you can help ensure a bright future for bees—and gain a stamp of royal approval.

This study was published in the journal BMC Genomics.

Reference

McAfee, A., Milone, J., Chapman, A., Foster, L. J., Pettis, J. S., & Tarpy, D. R. (2020). Candidate stress biomarkers for queen failure diagnostics. BMC Genomics, 21(571). http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12864-020-06992-2

All illustrations by Angie Lo.

About the Author

Angie Lo is an undergraduate student at the University of Toronto, currently majoring in Physiology and English. When not writing or studying, she can be found drawing cartoons, reading poetry, or cracking her tenth corny science pun of the day.