When Aquatic Invasive Species Take Over

What is an aquatic invasive species? It is non-native species that has been introduced into an area, and it is a big problem.

By Natasha Parkinson @schrodicatsci

The weather is hot, and everyone is trying to cool off any way they can. Everyone with a boat is out on the water, tubing, waterskiing, fishing, or cruising around. Anyone that has been around boats knows about boat safety: wear a life jacket, and don’t operate watercraft under the influence. But one aspect that is less discussed is preventing the spread of aquatic invasive species while you are on the water.

Aquatic invasive species

So what is an aquatic invasive species? Well, it is either a non-native species that has been introduced into an area, or a native species that is expanding its range. What makes them a nuisance is they have little to no natural predators, so they are able to multiply in number relatively unimpeded. And the reason they are of concern is they generally pose a risk to the environment, the economy, human health, or a combination of these factors.

Normally, these species are relatively contained. They would stay within a local system, geography being the primary cause that limits the spread (it’s hard for an aquatic species to leave the water on its own). However, thanks to humans and our activities, these species have more ways to spread. In fact, if we aren’t careful, anything can move around the world in 24 hours nowadays with our rapid trade systems. In North America, most aquatic invasive species are transported in two main ways: transportation of watercraft between bodies of water and intentional release.

RELATED: INVASIVE SPECIES: LUPINE INVASIONS

Local examples of invasive species: Alberta, Canada

In mid-July, I was fortunate to have the opportunity to attend an aquatic invasive species workshop put on by LICA Environmental Stewards, a nonprofit organization in Alberta that oversees the Beaver River watershed and airshed zone, through environmental monitoring and management, as well as community outreach and education. Not only did the workshop present a wealth of information, but it also brought in speakers from both the Alberta government and local environmental groups to inform those in attendance. Through these speakers I learned that currently, in Alberta, several species are being monitored and controlled for, including zebra and quagga mussels, crayfish, goldfish, phragmites, and flowering rush. Each case is unique, and that is why these key examples are best to learn from.

Zebra and quagga mussels

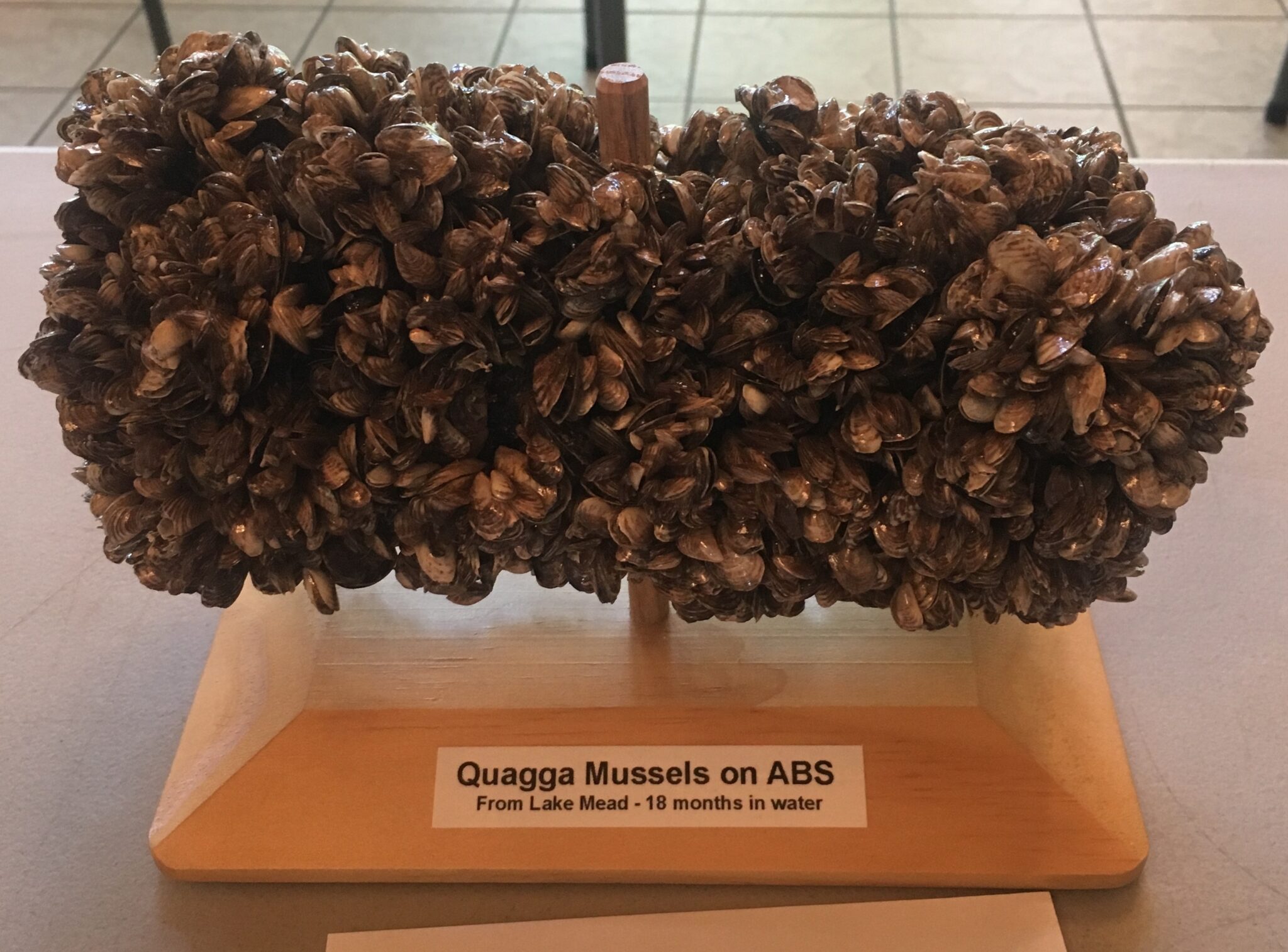

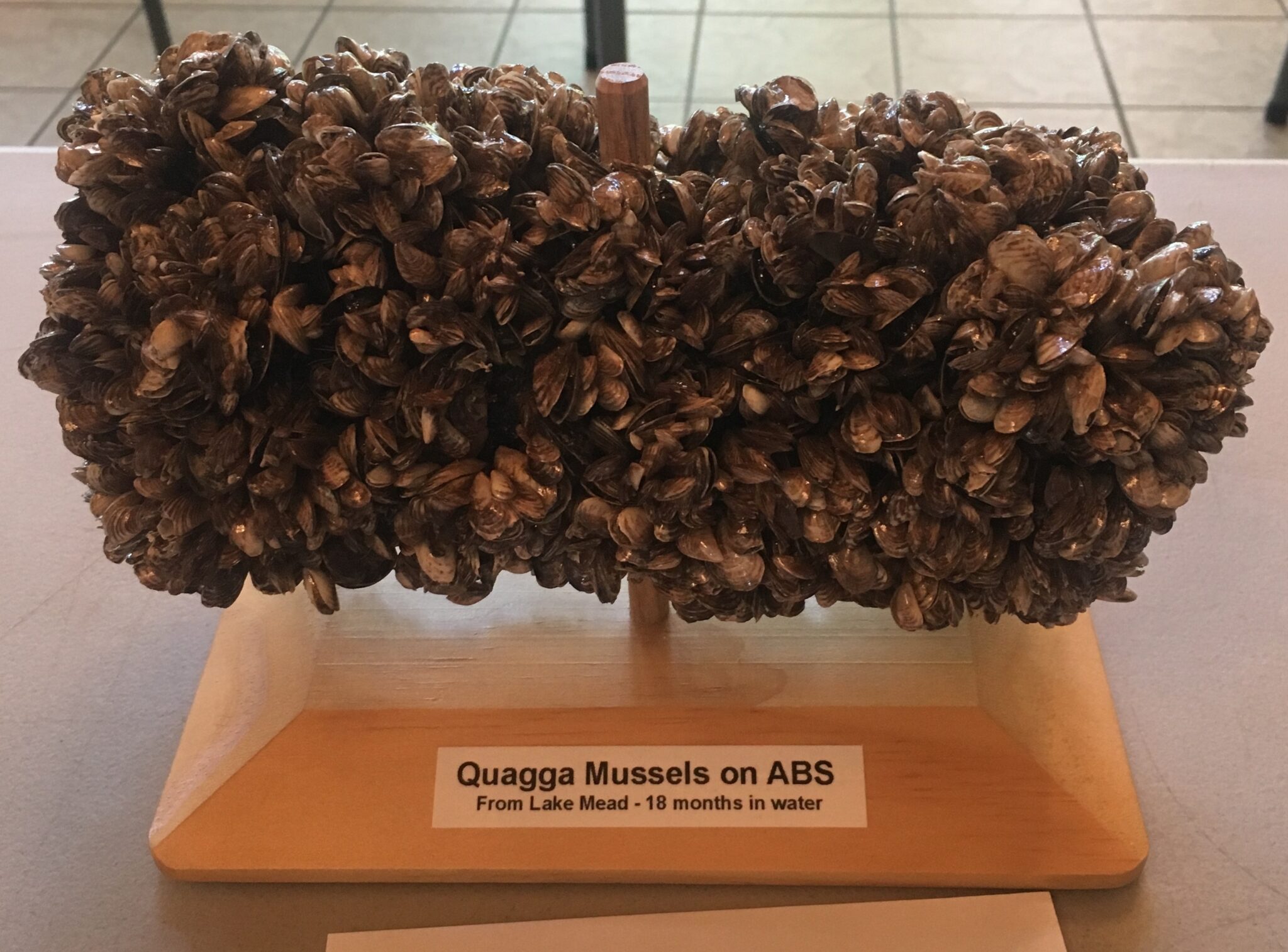

Scientists believe that, zebra and quagga mussels, native to Eurasia, showed up in North America in the 1980s, most likely brought over in the ballast water of transatlantic vessels. And they have quickly become a problem, as one female mussel can produce 1 million eggs each year. The eggs can attach themselves to anything submerged in the water—boats, piping, piers, docks, rocks. Quagga mussels are even able to attach to softer materials such as inflatable boats and belly boats. In boats, they can anchor themselves anywhere water is or has been: hulls, bilge pumps, inside engines. You’re probably thinking: if I take my boat out of the water for a few days, I should be good, right? Wrong, these mussels are capable of living out of water for up to 30 days.

So they are quite easily transported from one body of water to another, and they can cause quite the havoc once they get there. One mussel is capable of filtering 1 liter of water a day. In most cases, filtering is good, but not in this case. Zebra and quagga mussels filter out all the nutrients, oxygen, and other life-providing aspects of the water and spit out waste. This leads to increased occurrences of blue-green algae blooms, which are toxic if ingested by humans and animals (most blue-green algae advisory warnings involve a complete shutdown of the concerning lake—no water access). In addition, the Government of Alberta performed a recent assessment and determined that if Alberta were to become infested with zebra and quagga mussels, there would be an additional $75 million cost every year to maintain in-water infrastructure.

Fortunately, as of the latest checks, Alberta does not have any zebra or quagga mussels, thanks in part to preventative measuring being taken by the Alberta government (more on that later). Unfortunately, that cannot be said for some other noteworthy bodies of waters. Lake Winnipeg is a sad case of how destructive these molluscs can be. The species was confirmed to be present in 2013, and by 2016, the lake was completely infested.

Crayfish

Native to many watersheds, crayfish have been seen in other bodies of water where they had not in the past. They are an example of a native species expanding its range, and it is not doing so alone. Scientists have linked this recent spread of populations to their being transported by humans to their new homes. Whether it is a case of caught species being released after capture in the closest body of water or a case of someone trying to establish a population that they can later harvest, crayfish have been quickly adapting to their new homes. No assessment has been conducted, so the future impacts in these ecosystems are yet to be seen. Commonly found in moving rivers and streams, crayfish are quite easily captured (be sure to check with your local fishing regulations if you wish to go and catch some for dinner).

Goldfish

Goldfish—yes, the pet-store variety that you can buy for under $1—is another aquatic invasive species. Lately, when people find that they can no longer take care of their finned friend (whether their kid no longer looks after it or they are moving away and can’t take it with them), they release it in the closest storm drain or pond. Unfortunately, many of these ponds drain into natural bodies of waters where the goldfish flourish and push out native species. That finned friend that was the size of a large coin now grows to a whopping half kilogram. In addition to their increase in size, they are able to spawn multiple times a year, release 1,000 eggs each time, so long as the water is around 12 degrees Celsius. On the other hand, native fish only spawn once a year and rely on very specific conditions in order for it to occur, so their offspring are quickly outnumbered and unable to compete. One case of goldfish out of control occurred in stormwater collection pond in St. Albert, Alberta (just north of Edmonton). By the time the authorities were able to intervene and trawl the pond, they removed 45,000 individuals out of the pond. Fortunately, the pond was a closed system so the goldfish were unable to spread.

Phragmites

Phragmites is a reed that can reach over 4.5 meters in length. They grow in such dense thickets that animals commonly get stuck and die; it obstructs the flow of water and are known to reduce habitat for fish, birds, and other wildlife. Some varieties of phragmites are native, and the only way to tell the difference is through DNA testing. What makes phragmites spread so quickly and widely is they have two ways of spreading. Like most plants, they have seeds that are easily transported. It has been speculated that the railway, commonly found along railways, is what helps phragmites spread. Once rooted, phragmites have an extensive rhizome system that allows new reeds to pop up from the ground, enabling a single individual plant to cover large areas. Unfortunately, the reed cannot be picked or cut down, as even the smallest fragment can create a new plant.

Flowering Rush

Now illegal for sale in British Columbia and Alberta, this aggressive plant was available for purchase as a pond plant up until 2010. It quickly became a problem as it is capable of outcompeting everything. Capable of floating to new places to spread, the smallest fragment of the plant can spawn a plant reaching up to 4.5 meters underwater and create dense mats of plant mass (solid enough to support the weight of an adult human). However, birds are incapable of nesting in it and fish can’t spawn in it. Back in 2013 when Calgary, Alberta, flooded, a group of the plants that had been located in the Calgary zoo pond was flushed out and downstream. Ever since, flowering rush has taken over the Bow River into Saskatchewan. Once it reaches a large enough size, it is almost impossible to eradicate. To date, authorities and scientists have tried benthic mats to block out the sun (and flowering rush just grows around the mat), mechanical removal with boats (which just broke the plant into smaller pieces, which allowed further spreading), steam (but the water temperature could not be raised high enough to kill the plants), and scuba divers with vacuums (very expensive, time consuming, and only mildly successful). The only success they have had so far is in prevention.

What is being done to prevent the spread

Currently, the best tactic for tackling these species is prevention, as for many species, once they take over an area there is not much that can be done to reverse the invasion. Both the Canadian and Albertan governments have implemented regulations to prevent the spread of aquatic invasive species. These include the Prohibited Species List, which exclude species that cannot be brought into the country (including zebra and quagga mussels); quarantine provisions for fish being brought in for the pet and aquarium industry to prevent the spread of diseases and parasites; allowing Royal Canadian Mounted Police and peace officers to be able to enforce the Aquatic Invasive Species Act; prohibiting the release of subject water (including aquarium water) and non-native species, among other mandates. In addition, scientists and conservation officials are currently monitoring 112 locations throughout Alberta alone to determine whether any new invasive species are introduced and to ensure that existing populations do not spread further.

In order to ensure that species do not unwittingly enter Alberta, and Canada generally, mandatory watercraft inspection points are set up at various points. In Alberta, as well as other locations, it is mandatory to pull into these inspection stops if you have a watercraft of any kind, trailered or inflatable. At some of these locations, conservation officers are assisted in their inspection by very special dogs. It is important to note, these dogs are strictly trained to find invasive species (in the case of boat inspections, they are looking for zebra and quagga mussels)—they are not looking for drugs, alcohol, or firearms. As much as such items can be a concern, they are not a concern for these dogs and their handlers. Last Wednesday, I had the opportunity to meet one of these working dogs, Seuss, along with his handler. Seuss and the other two dogs that work in Alberta, Hilo and Diesel, come from the program Working Dogs for Conservation, based in Montana. Dogs that are a part of this program are rescued from shelters and are trained to fill various positions, from finding rare animals to searching for invasive species and detecting smuggled/poached animals. In the case of Seuss, Hilo, and Diesel, they are trained to search for zebra mussels (in boat inspections, shoreline checks, and water samples) and Thesium plants, and they are currently learning to detect wild boars via their scat. Without these dogs, inspections would take much longer, and there is a chance that some could be missed by the human eye that can be picked up by one of the dogs’ keen sense of smell.

RELATED: Battling Invasive Species with Virtual Ecology

What can you do?

Want to help prevent the spread of aquatic invasive species but don’t know how you can contribute? Well, you are in luck—there are plenty of ways:

Clean, Drain, and Dry Your Boat and Gear, especially when going between different bodies of water. Not only does it prevent stowaway species, it also prevents the spread of diseases and parasites that could negatively affect an ecosystem. Be sure to pull your ballast plug; it is mandatory and prevents the spread of invasive species, diseases, and parasites. As for drying your gear, best practices are to allow it to dry outside in the sun for 24 hours.

Don’t Flush Your Goldfish. Flushing your dead goldfish could potentially introduce bacteria or viruses into the local water system. For dead pet fish, it is recommended that you bury them. Biodegradable burial pods are available, like Fishpods by Pawpods. If you have a pet fish that you don’t want any more and no one will take it, whatever you do, do not release it into the wild, as it can quickly overrun a water system. One more humane method to euthanize your fish is by putting them in a plastic bag with water and placing them in the freezer. As the water cools, the fish slows down and drifts off to the other side, so to speak.

Don’t Let It Loose. Do not release goldfish or other species or live bait into bodies of water different from where they were caught or used.

Don’t Pull or Dig It. If you see any invasive plants, don’t pull it out or dig it up. Many species only need a small piece to create a new plant, and in the process of pulling it out or digging it up, pieces of the plant could be transported to another area and expand there. Also, some species of invasive plants can be harmful to you. Rather than trying to remove it, report it to the proper authorities that can remove it properly and prevent it from spreading further.

Report It. If you spot an invasive species, report it, even if you are in doubt about whether it is an invasive species. I spoke with an individual who reviews some of the reports, and she said that she would rather have a report that turns out to be a native plant that is not a concern than have an invasive species go unreported. There are two different ways to report. In Alberta, there is a 24/7 hotline that you can call: 1-855-336-BOAT (2628). When you call in, be sure to report the date and time; the name of the river, stream, or lake; GPS coordinates (if you have it); description (number of invasive species individuals, species, etc.); and take photos if possible. A second way to report is being brought to Alberta and is currently used throughout North America: the app EDDMapS. You submit a picture of the invasive species through the app, which then takes the location from your phone and develops a report for you. For those not located within Canada, here are some hotlines you can call should you notice a non-native species:

- United States: 800-STOP-ANS (877-786-7267) or report using the EDDMapS app

- United Kingdom: 0370 850 6506

- European Union: report on the mobile app Invasive Alien Species Europe, available on both Apple and Android devices

- Australia: contact the Community Information Unit of the Department of the Environment and Energy at 1800 803 772 for further information

- Other countries: look at their country’s Department of Environment website for further information or contact details to find out where to report (if a program is present in your country)

Aquatic invasive species are a serious issue for our environment, our economy, and our health. It is an issue that is not going to go away without our help and due diligence. Since there are still no tried-and-true method to eradicate many invasive species, prevention is the best policy we have right now. If we all help out, we can prevent the destruction of more ecosystems. For more information, check your local fishing and boating regulations. In Alberta, you can get further information at aep.alberta.ca.

—Natasha is the blogger and visionary behind Schrodinger’s Cat. After graduating from the University of British Columbia with a bachelor of science in earth and environmental science, life science, and physics, she found that she was not done asking all those important questions that she had to know (three majors had only begun to present some of the many major questions to be answered). Schrodinger’s Cat is about exploring the science that is all around us and making science accessible to everyone. No PhD needed. This post has been adapted from the original, which appeared on Schrodinger’s Cat.net.