While anticholinergics help manage many common medical conditions, they affect thinking and memory, possibly leading to Alzheimer’s disease.

By Alex Weigand

The following is a fictional story. Joan is a 75-year-old woman who lives a typical postretirement life. She loves spending time with her grandchildren, although she has to be sure to take medication for her overactive bladder when they go to the movie theater or on a long road trip. She has two cats she adores, even if it means having to take allergy medication to minimize her sneezing when she is around them. She also takes medicine for her heart to manage her high blood pressure. Recently, Joan’s husband has noticed that she has been having trouble with her memory, such as forgetting where she put her keys or glasses, having trouble remembering names, and getting lost on her usual walking route. Joan and her husband are concerned that she may be entering the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, and they worry that there is nothing they can do to reduce this risk.

Because I have numerous family members who are battling against Alzheimer’s disease, this research topic is very near and dear to my heart. One of the most difficult aspects of this condition is that currently there is no available treatment. It is true that there are a number of lifestyle changes that can help reduce the risk of a person developing Alzheimer’s, including healthy eating, exercise, and social engagement. However, taking anticholinergics, a class of medications commonly prescribed or purchased over the counter for conditions such as allergies, overactive bladder, heart problems, and low mood, may have a negative impact on a person’s thinking and memory. But, importantly, reducing the use of these medications may serve as another lifestyle change that can lower a person’s Alzheimer’s risk.

Alzheimer’s disease and your medicine cabinet

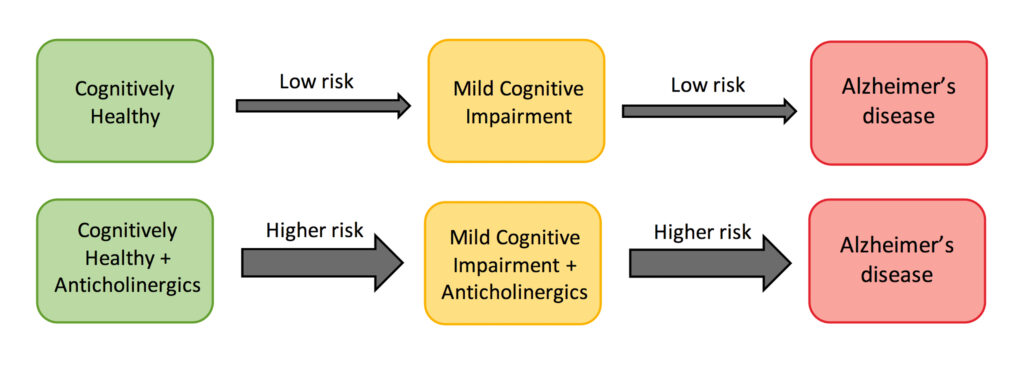

Our study examined a group of older adults with no memory or thinking problems who were either taking no anticholinergic medications or consistently taking at least one. Importantly, these medications reduce the amount of a chemical in the brain that is important for thinking and memory, and therefore they may increase a person’s risk of cognitive decline including Alzheimer’s disease. We found this theory to be true: Individuals in our study who were taking anticholinergic medications had nearly 50 percent additional risk of developing mild cognitive impairment, a precursor to Alzheimer’s.

We also investigated whether individuals who had increased biological risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease because of either a genetic predisposition or spinal fluid markers would be particularly affected by anticholinergic medications. Our results indicated that individuals taking anticholinergic medications who were also genetically predisposed were two and a half times more likely to develop cognitive impairment, and those taking anticholinergic medications who also had spinal fluid Alzheimer’s markers were four times more likely to develop cognitive impairment relative to the low-risk group.

Additionally, individuals taking anticholinergic medications displayed a faster rate of decline in particular cognitive skills, including memory, language, and multitasking. Those who were also genetically predisposed or had spinal fluid Alzheimer’s markers experienced cognitive decline at an even faster rate than the rest. Importantly, this decline occurred even though none of the participants had memory or thinking problems at the start of the study.

Exploring alternate approaches with your doctor

These findings have important implications for older adults taking anticholinergic medications. Adjusting the levels of these medications or finding alternative options may reduce a person’s risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, even if they have no current cognitive problems.

However, it is important to remember that these medications serve other important functions, and they should not be altered or discontinued without a discussion with a doctor. If you or a loved one are taking medications for conditions such as allergies, overactive bladder, blood pressure, depression, or others that you believe may be harmful to your thinking and memory, consider talking with your doctor about potential alternative options or about reducing medication dosages. A full list of anticholinergic medications and recommended alternatives can be found here.

Does Brain Cholesterol Control Alzheimer’s?

Fictional story continued: Joan spoke with her doctor about her memory concerns. Having learned about the potential harmful effects of certain medications, she brought it up with her doctor and asked if she could have her medication regimen reviewed. Her doctor recommended that she reduce the dosage of her allergy medication to see if it would still be effective at a lower level for her cat allergies. He also pointed out that she could take her overactive bladder medication only prior to certain excursions, where it would be difficult to find a bathroom, rather than daily and that she could rely on regular bathroom visits or panty liners on other days. He also suggested that she continue to take her blood pressure medication because of its importance, and he replaced the specific type of medication with one that was less harmful to the brain. After making these adjustments, Joan saw some improvements in her memory. Although she was still experiencing some memory problems, she was happy to have made positive changes that were within her control and that could help reduce her risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

Learn more: Volunteers Are Helping with Alzheimer’s Research by Playing an Online Game

References

Weigand, A. J., Bondi, M. W., Thomas, K. R., Campbell, N. L., Galasko, D. R., Salmon, D. P., Sewell, D., Brewer, J. B., Feldman, H. H., Delano-Wood, L., & Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (2020). Association of anticholinergic medication and AD biomarkers with incidence of MCI among cognitively normal older adults. Neurology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000010643

Aging Brain Program of the IU Center for Aging Research. (n.d.). Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden Scale. American Delirium Society. https://americandeliriumsociety.org/files/ACB_Handout_Version_03-09-10.pdf

The information contained in this article is for informational purposes only and is not intended as health or medical advice. Always consult a physician or other qualified health provider regarding any questions you may have about a medical condition or health objectives.

About the Author

Alex Weigand is a 3rd year PhD student in the San Diego State University/University of California San Diego Joint Doctoral Program in Clinical Psychology and National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellow working with Dr. Mark Bondi. Her current research focuses on improving the characterization of cognitive and biological changes that occur during the preclinical period of Alzheimer’s disease to ultimately reduce Alzheimer’s risk. Outside of the lab, she works to promote positive mental health among graduate students and to improve science communication with the nonscientific community.