By Shelby Nilsen (@shellbeegrace)

Climate change is already affecting many habitats and ecosystems. As a result, scientists are working to understand how the rising temperatures we face might affect extant animals—that is, those species that are still surviving—including tardigrades, some of the toughest organisms around, which are well known for their ability to adapt to extreme environments.

In the face of certain environmental cues, tardigrades enter cryptobiosis, a state in which all metabolic processes stop until the organism’s surroundings become favorable again. This remarkable survival tactic allows tardigrades to withstand many types of severe conditions, such as extreme cold, short exposures to extreme heat, high pressure, radiation, and even outer space. It turns out, however, that even these incredibly resilient organisms have an Achilles heel: prolonged exposure to high temperatures.

Survival skills of the fittest… tardigrade

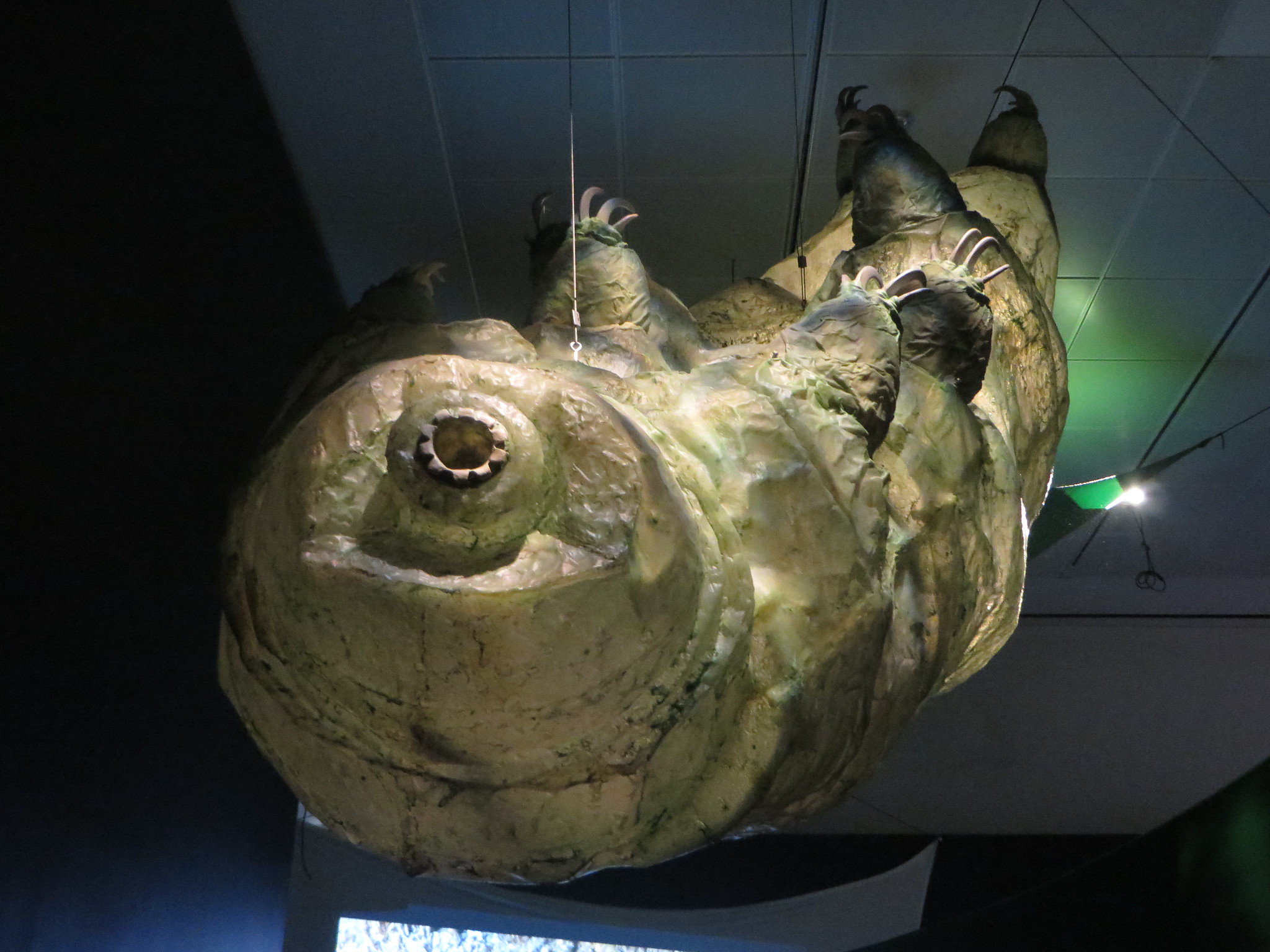

Tardigrades, often called water bears or moss piglets, are microscopic aquatic invertebrates that live in marine, freshwater, and on-land microhabitats around the world. They are short statured and chubby, with four pairs of legs each ending in multiple claws or sucking disks.

All tardigrades need water to feed and reproduce in their active state. Those living on land may temporarily lose access to water when their environment dries out. When this happens, they first retract their legs and head. Then they get rid of all the water in their bodies through a process called desiccation, causing them to shrivel up into tiny balls and enter an inactive state called the tun form. Tardigrades will emerge from this desiccated form, rehydrate, and become active again only when they have access to water.

How hot is too hot?

Researchers from the Department of Biology at the University of Copenhagen wanted to test the tolerance of tardigrades to prolonged periods of extreme temperatures. They took specimens of Ramazzottius varieornatus, a tardigrade species found in transient freshwater habitats, from a roof gutter in Nivå, Denmark. Both active and desiccated forms of these tardigrades were exposed to 24-hour periods of extreme heat. The researchers then recorded the ratio of the organisms that survived at each temperature level. For the purpose of this study, lethal temperature was determined using a 50% mortality rate. This means that the highest survivable temperature was defined as the point where 50% of the tardigrades were deceased and 50% remained alive.

The researchers estimated the proportion of tardigrades that survived 2, 24, and 48 hours after temperature exposure. They identified living tardigrades by watching for movement of the legs or main body. If the tardigrades did not move, they were considered dead. The researchers recognize that inactivity did not necessarily mean the tardigrades were, in fact, deceased, and that the activity data may represent a small underestimation of survival rates.

First, the researchers studied tardigrades in the active state. They tested four different temperatures ranging from 30 to 40 degrees Celsius (86 to 104 degrees Fahrenheit). The highest tolerable temperature at which 50% of the active tardigrades survived was 37.1 degrees Celsius (98.78 degrees Fahrenheit). It was found that adding acclimation steps to the experimental process increased the ability of the tardigrades to survive higher temperatures. After intermediate acclimation temperatures were added, the active tardigrades achieved 50% mortality at a slightly increased temperature of 37.6 degrees Celsius (99.68 degrees Fahrenheit).

The desiccated specimens, which were tested in two groups, did much better. The first group received a 1-hour exposure, and the other received a 24-hour exposure. After exposure and before counting, both groups were rehydrated. The 1-hour exposure group tolerated temperatures up to 82.7 degrees Celsius (180.86 degrees Fahrenheit). This data supports previous studies that show high tardigrade survival rates following short exposures to extreme heat. However, after 24 hours, the tolerable temperature dropped to 63.1 degrees Celsius (145.58 degrees Fahrenheit).

These results show that active tardigrades are vulnerable to high temperatures, although their tolerance may improve if temperatures increase slowly over time. Desiccated tardigrades, on the other hand, are less vulnerable to high temperatures than active ones. Even so, the longer the exposure, the greater the drop in their survival rates. The researchers hypothesize that the survival of tardigrades in their desiccated state depends on maintaining structural integrity, and high temperatures may destabilize proteins essential for survival in that state.

Even the tardigrade affected by climate change

Of all the things scientists have thrown at the tardigrade, high temperatures appear to be its weakest point. Further research on heat tolerance could improve understanding of the limits of tardigrades and other organisms that react similarly to extreme environments.

It is important to understand how our actions—or inaction—today might affect extant animals now and in the future. Climate change is having an impact on every creature on this earth, and even the enduring tardigrade is at risk.

This study was published in Scientific Reports. It was funded by The Danish Council for Independent Research and Carlsberg Foundation. VILLUM FONDEN provided further support through a research grant.

—Shelby Nilsen writes research-backed health and science content for lay audiences online. She is a full-time traveler, pathology enthusiast, and lover of bad puns. Connect with her via her website or on Instagram @shellbeegrace.

Reference

Neves, R. C., Hvidepil, L. K. B., Sørensen-Hygum, T. L., Stuart, R. M., & Møbjerg, N. (2020). Thermotolerance experiments on active and desiccated states of Ramazzottius varieornatus emphasize that tardigrades are sensitive to high temperatures. Scientific Reports, 10, 94. doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-56965-z