Droughts can wreak havoc on food supply and crop production, but a new study shows that ethanol can help crops survive.

Ethanol, a simple alcohol made from grain, is known as a tool for combating climate change. While ethanol is generally thought of as a renewable fuel source, a research team from the RIKEN Center for Sustainable Resource Science in Japan has explored another important benefit of ethanol: it may be a way for plants to fight off devastating droughts.

How droughts hurt crops

The study, led by researcher Motoaki Seki and a team of more than two dozen scientists, comes at a time of unprecedented droughts driven by rising temperatures. Coupled with a growing global population that’s expected to reach 9.5 billion people in the next three decades, droughts are likely to devastate food supplies, making it all the more imperative to find a solution as quickly as possible.

Lack of water impacts plants’ ability to turn sunlight into sugar, which limits their growth. Tiny pores in the surface of plants’ leaves, called stomata, regulate how plants take in and release gasses, as well as their ability to retain water.

Much of the existing research on how droughts affect plants focuses on these stomata’s ability to control transpiration, or how much water vapor is released from a plant. A different study from 2017 showed the researchers that ethanol can help lessen the effects of salt and heat stress. The researchers also knew that plants produce ethanol when they can’t access enough water. Working off those ideas, Seki and his team hypothesized that giving plants ethanol in times of drought might just do the trick.

Ethanol helps plants de-stress

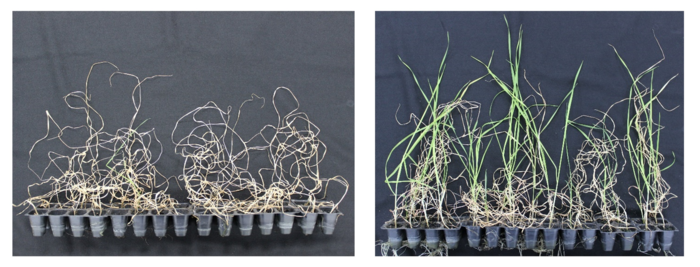

They tested the theory with Arabidopsis thaliana, a plant commonly used in scientific experiments, as well as with rice and wheat seedlings, which are more likely to be grown for widespread food supply. Growing the seedlings under controlled laboratory conditions with plenty of water, the researchers treated their soil with 3% ethanol—which soaked in from the bottom—and stopped watering the plants when they were a few weeks old.

After a period of no water, researchers began watering the seedlings again with encouraging results: roughly three-quarters of the ethanol-treated plants bounced back from the drought period. Meanwhile, only 5 percent of the untreated plants survived.

To dig deeper into why this happened, the researchers measured how far open the plants’ stomata were under drought conditions. Reacting to the ethanol pretreatment, Arabidopsis leaves increased in temperature and closed their stomata. This ultimately let them hold on to water vapor more effectively than the untreated plants, even by the end of the drought period.

RELATED: Steroid Hormones Protect Cotton from Drought

Then the team took things even further and analyzed the genes that the plants activated when they reacted to drought conditions. They found that the ethanol-treated plants began reacting even before the researchers had stopped watering. When Seki and his team tracked where the ethanol went inside the plant after it was picked up by its roots, they found that much of it went to the leaves. These leaves then produced sugars and photosynthesized at much higher rates than the plants’ untreated counterparts.

By examining the way plants metabolize ethanol, and what genes are activated in doing so under drought conditions, the researchers confidently landed on a conclusion: pretreating soil with ethanol could help plants weather conditions that usually destroy them.

Hope for fighting hunger

Since agriculture is already so dependent on external factors like temperature, precipitation, and sunlight, it can be tricky to introduce new management methods for problems like droughts. This challenge only compounds when we consider the shifting dynamics of climate and the necessity of managing these changes with solutions that are financially sustainable and safe for humans.

Seki and his team believe that using ethanol treatment to stave off drought provides all these things. Ethanol is safe when used in this manner, and while genetically modified organisms (GMOs) do provide drought-tolerant varieties of some plants, these are often expensive to develop and purchase. By contrast, ethanol is cheap and widely available—no regional lab required.

This means that for the planet’s current and future food-scarce regions—many of which lack the financial resources for chemicals or GMOs—there is hope for keeping people from going hungry, rain or shine.

This study was published in the peer-reviewed journal Plant and Cell Physiology.

Reference

Bashir, K., Todaka, D., Rasheed, S., Matsui, A., Ahmad, Z., Sako, K., Utsumi, Y., Vu, A. T., Tanaka, M., Takahashi, S., Ishida, J., Tsuboi, Y., Watanabe, S., Kanno, Y., Ando, E., Shin, K.-C., Seito, M., Motegi, H., Sato, M., Li, R., Kikuchi, S., Fujita, M., Kusano, M., Kobayashi, M., Habu, Y., Nagano, A. J., Kawaura, K., Kikuchi, J., Saito, K., Hirai, M. Y., Seo, M., Shinozaki, K., Kinoshita, T., & Seki, M. (2022). Ethanol-mediated novel survival strategy against drought stress in plants. Plant and Cell Physiology, 63(9), 1181–1192. https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pcac114

About the Author

Mackenzie Myers Fowler is a science writer, avid knitter, and former field station ragamuffin. She holds an MFA in nonfiction writing but would be a soil scientist if she could do it all over again. She lives in Michigan with her husband, her cats, and a plethora of houseplants.