Is there a genetic component to friendship? Mice prefer friends who are genetically similar to them, regardless of other factors.

By Emery Haley

Have you ever met someone and knew immediately that you liked or disliked them without really knowing why? Chances are, you have, and a recent study from the University of Maryland School of Medicine suggests your genes may be the reason.

Psychology research has shown that human friends are more genetically similar than people who aren’t friends. Since friends tend to live near each other and share racial and cultural backgrounds, it wasn’t possible to tell if the genetic similarity was a coincidence or an important factor in friendship. Fortunately, humans aren’t the only animals that form friendships.

Mice making friends

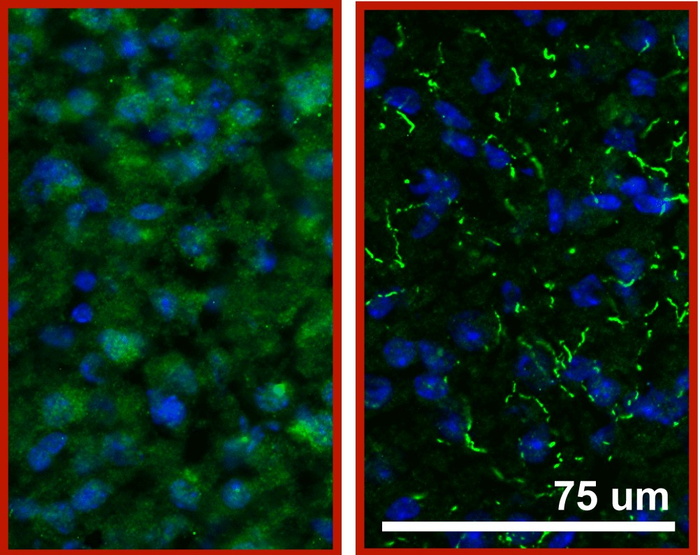

Mice also form friendships, and using mice, researchers could test whether genetic similarity contributes to the instantaneous preference to form friendships with some individuals over others. The researchers compared mice with different genetic expression levels of PDE11A, an enzyme active in the hippocampus. The hippocampus is a brain structure that deals with memory, emotion, and social behavior, like making friends. The mice in the study included normal mice; knock-out mice, which do not express the enzyme at all; and heterozygous mice, which express about half as much enzyme as the normal mice.

For the study, mice were put in a cage where they could choose to interact with either of two chambers. Inside one was a new object, something mice instinctively investigate, and inside the other was a new mouse. The new mouse in the chamber could be genetically similar (the same expression of enzyme) or genetically different (different expression of enzyme). When a mouse spends more time with the new mouse than the new object, it mimics the instant preferences humans form at the start of a new friendship.

Dogs are some our best friends. Learn more about their genetics: Working Dogs Traded by Ancient Cultures?

Opposites DON’T attract

The mice only preferred spending time with the new mouse when it had similar genetics. Normal mice preferred mice with normal enzyme expression, while knock-out mice preferred other knock-out mice. Heterozygous mice, which express less enzyme than the normal mice but more than the knock-out mice, did not show a preference. The researchers believe these mice did not have a preference since they were not genetically similar to either the normal mice or the knock-out mice.

Finally, the researchers repeated the experiment using another strain of mice, albino ones. These mice express a slightly different version of the PDE11A enzyme. If the newly introduced mouse was from a different strain of mice (dark-furred mouse introduced to albino or vice versa), the mice did not show a preference between the normal, knock-out, or heterozygous expression levels. However, the albino mice showed the same expression level preferences as the dark-furred mice when both mice in the experiment were albino.

The researchers also performed the experiment with pairs of male mice or pairs of female mice and with pairs of adult mice or pairs of young mice. In each case, the preference for genetically similar mice was the same.

Related: The Effect of Exercise on Your Genes

To try and find out why the mice show a preference for friends with similar genetics, researchers investigated whether the new mouse’s activity level was a factor and found that it made no difference. They also did the experiment with just the pheromone smell of the new mouse, not the mouse itself, placed in the chamber. The mice did not form the same instant preferences for the pheromones. The researchers say they have a few more ideas to test and they still hope to learn what behavior or trait is being influenced by the differences in PDE11A.

Related: Epigenetics of offspring influenced by parents’ diets

Less social or differently social?

The results of this study could change how people with conditions like autism are viewed. Why is that? The albino mice had previously been called less social than the dark-furred mice. This was based on comparing interactions between an albino mouse and a dark-furred mouse with interactions between two dark-furred mice. However, when two albino mice were tested, they interacted more than two dark-furred mice. The albino mice aren’t less social, they just have a different social preference. The way the researchers’ thinking about the behavior of albino mice changed could also apply to people. For example, people with autism may socialize more with other autistic individuals specifically.

This new understanding of a genetic basis for friendship could also have other widespread effects on how we understand and arrange social interactions. The researchers plan to study the PDE11A enzyme further and hope the results will help to develop new treatments for people with conditions that cause social withdrawal, like PTSD and schizophrenia. They also imagine a future where these genetic factors could help match up patients and doctors, or students and teachers, to make the most of these interactions.

This study was published in the peer-reviewed journal Molecular Psychiatry, a Nature publication.

Related: Asthma, Genetics, and the Environment

RELATED: How Does EMDR Therapy Work?

Reference

Smith, A. J., Farmer, R., Pilarzyk, K., Porcher, L., & Kelly, M. P. (2021). A genetic basis for friendship? Homophily for membrane-associated PDE11A-cAMP-CREB signaling in CA1 of hippocampus dictates mutual social preference in male and female mice. Molecular Psychiatry. doi: 10.1038/s41380-021-01237-4

About the Author

Emery Haley is a nonbinary cell biologist with a passion for diversity in STEM. They are currently a PhD student at Van Andel Institute Graduate School and are planning to pursue a career in science communication. Connect with them on Twitter @EmeryHaley2 and LinkedIn!