A picture is worth a thousand words. Scientific illustration is more than just a cool art form. It conveys technical details about research that other tools cannot.

By Shayna Keyles

Scientific illustration is more than just cool artwork. It’s a way of conveying technical detail that other tools can’t provide; of capturing the complexities of organisms or fabrications that are too small, too far away, too extinct, or too difficult to dissect; of sharing intimate research in a globally understood language.

Pictures of discovery

Illustrations have always been used to track observations and inform others. There are drawings of animals in the Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc caves in France that date back 30,000 years and are accurate enough for researchers to identify at least 13 of the species depicted. Fifteen millennia later, a depiction of a mammoth with a smudge near its shoulder might have been the first intentional scientific illustration: that smudge had the shape of a heart and was located near where the heart would have been. Fast-forward another fifteen millennia; the scholars in Alexandria had an entire library devoted to their observations. Herophilus, a Greek physician in Alexandria, regularly performed dissections and illustrated his subjects to learn more about human anatomy. He is believed to be one of the earliest pioneers in using illustration as a technical tool.

Early scientific discoveries were solidified and propelled by illustration. From the early experiments in Greece and Egypt to the later innovations of the European Enlightenment, visual representation was necessary for conveying often complicated information. In the words of The Guild Handbook for Science Illustration, “Imagine a description of a yellow butterfly in words only! What shade of yellow? What is the wing shape? What does the color pattern look like? These deficiencies in communication made obvious the need for illustration. Thus, artists accompanied early exploring expeditions to record discoveries visually.”

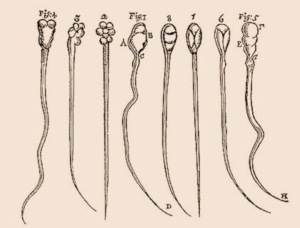

Cameras were not in use until the early 1800s, so to share visual data prior to that point, scientific illustration was necessary. But even now, when cameras are just a cell phone away, illustration still holds power. Unlike a photograph, an illustration can showcase numerous perspectives at once. “The skilled scientific illustrator can clarify multiple focal depths and overlapping layers, emphasize important details, and reconstruct broken specimens on paper—results unattainable through photography. Structure and detail may be depicted with cutaway drawings, transparencies, and exploded diagrams,” according to The Guild Handbook.

Flipping through collections of scientific illustrations from the past few centuries, you’ll find fascinating images that seem both meticulously rendered and strangely abstract at the same time. This is because many scientific illustrations are drawn so as to represent not the single specimen used as a reference, but a generalized version of a species or event. This much is said in the preface to a collection by seventeenth-century illustrator and collector Albertus Seba: “The elements important for human identification are rendered better and considerably more clearly in the picture than in the actual specimen itself.”

Scientific illustration in practice

The goal of scientific illustrations varies depending on the artist and the need. Some illustrations are used to identify poisonous versus edible flora and fungi, for example, and the immaculate detail afforded by illustration, as opposed to photography, is especially useful in the field. Medical textbooks will often have scientific illustrations instead of photographs for this same reason.

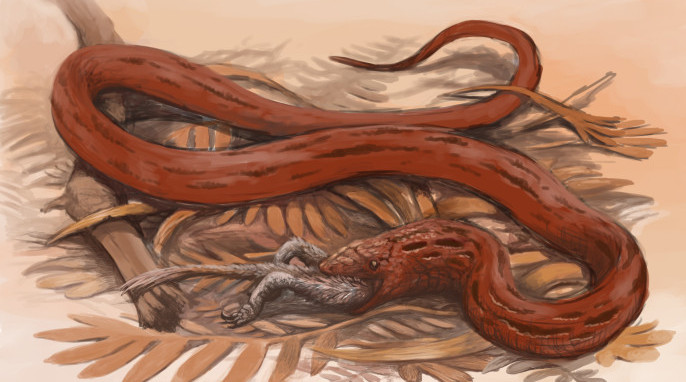

Minneapolis-based paleoartist Emily Willoughby illustrates prehistoric organisms and has a keen interest in depicting dinosaurs that are not quite bird, but aren’t too far off, either. Without illustrations like hers, it would be difficult to visualize and learn from dromaeosaurs, troodontids, and oviraptorosaurs. Researchers point to these creatures as evidence that there is an evolutionary link between dinosaurs and birds.

“For me,” Emily says, “the attraction to this field has always been the unique power that artworks hold in the field of paleontology, which does not enjoy the benefit of direct observation or photography of its living subjects.”

RELATED: AMBER PRESERVES DETAILS OF ANCIENT BIRD WINGS

Emily’s illustrations help researchers, students, and educators alike grasp concepts that otherwise don’t lend themselves to visualization. Paleoart especially helps fill in the blanks in the fossil record. Emily’s illustrations of non-avian dinosaurs, for example, were recently published in a book that addresses the evolution/creation debate. The depictions of the evolutionary chain of events makes the argument for evolution much stronger.

Laura Macias, a scientific illustrator in San Francisco, also uses her illustrations to trace evolutionary history. Her preferred subjects are cnidarians, echinoderms, and cephalopods (including jellyfish, urchins, and octopus, among others), which have some of the oldest recorded fossil records.

RELATED: PREHISTORIC CROCODILES RULED ANCIENT PERU

For Laura, science illustration is an essential teaching tool, especially for people who are visual learners. Visual stimuli can engage people and introduce new subjects, spark new interests, and reinforce new ideas. “No matter how extensive your knowledge of a subject can be, we humans always respond to what is visually alluring,” she explains. “Once you have piqued an interest and engaged your audience, you can then proceed to expanding the understanding.”

RELATED: PALEONTOLOGISTS DIGITALLY RESTORE DINOSAUR FOSSILS

Science communicators have the responsibility of conveying a complicated reality to numerous individuals, most of whom don’t come from an expert background. Accuracy is important, but so is helping the public achieve an understanding. Scientific illustration is an excellent tool that can not only foster that understanding, but also cultivate interest, highlight details, and make complicated ideas more accessible. And you know what they say: a picture is worth a thousand words!

References

Sena, Albertus. Cabinet of Natural Curiosities. Reproduction. Cologne: Taschen, 2011.

Interviews with Emily Willoughby and Laura Macias.

https://gnsi.org/science-illustration

Featured image: Dakotaraptor steini. Hell Creek Formation. 66 Ma. Artwork by Emily Willoughby.