Where do garbage patches come from, what garbage is in them, how do they form, and how can we clean them up once and for all?

There’s an infamous presence looming far out in the Pacific Ocean. But rather than some deep-sea kraken or other mysterious mythological beast, this monstrosity is floating right on the surface…and is unfortunately very real. It’s known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

Thanks to new research from a team of physicists in the U.S. and Germany, we may have more insight as to how these giant swaths of garbage form and what we can do to more effectively clean them up, or at least prevent them from getting larger.

What are garbage patches?

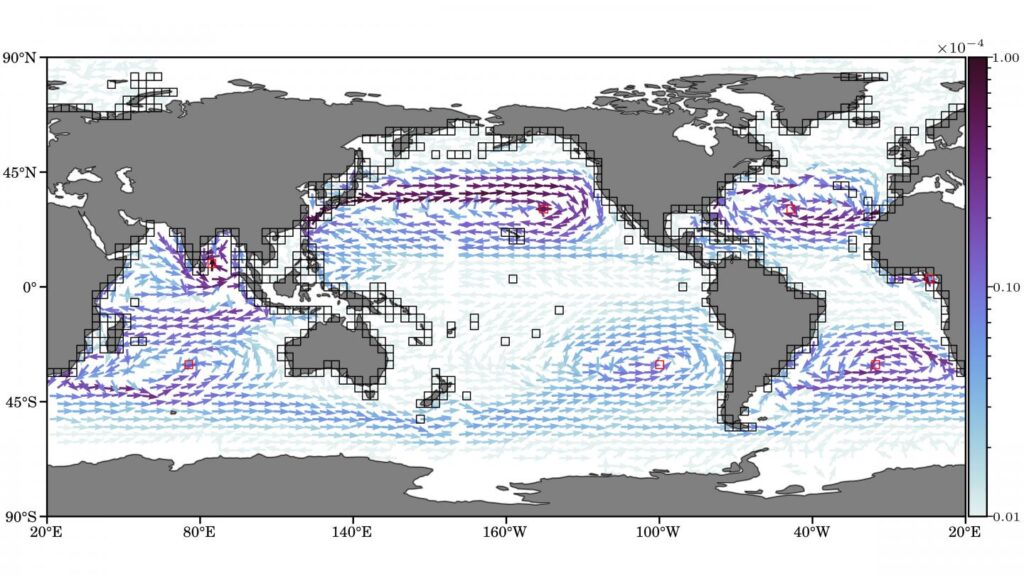

The researchers behind the study, which was published in March 2021, were curious about how plastic pollution travels from coastlines to the middle of the ocean. Through various models, they examined how different systems of rotating subtropical currents–also known as gyres–affect one another, allowing debris to build up in certain areas of the ocean versus others, similar to the way pieces of food collect in a central location when you drain your sink after washing the dishes.

According to the Marine Debris Program within the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the earth has five gyres in its oceans: two in the Atlantic, two in the Pacific, and one in the Indian Ocean.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch is located in the North Pacific gyre, between California and Hawaii. It contains everything from large ocean fishing equipment to microplastics smaller than 5 millimeters, which may make cleanup even more challenging in addition to its extremely remote location. However, even though the planet’s oceanic garbage patches exist far away from humanity, the threats they pose hit closer to home: they can cause marine animals to starve or become injured, and can transport invasive species from one area to another.

RELATED: ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY MATTERS WITH SCIENCE DEBATE

Tracing the trash path

Using historical data from buoys belonging to NOAA’s Global Drifter Program, the researchers mapped out how the ocean’s surface water behaves. With this information, they determined the probability of trash being moved from one region of the ocean to another and created “pollution routes” that show not only debris movement, but its re-entry back into the system after being beached onshore.

Another tool the researchers used, transition path theory, allowed them to connect the dots between a garbage island, its source, and potential stopping points in gyres along the way.

“In this work, we focus on pathways from the coast to the subtropical gyres, from one gyre to another, and from the gyres to the coast,” says lead author and University of Miami researcher Philippe Miron.

Further, the study shows that not all garbage patches are created equal. The researchers not only determined pathways of pollution, but the ability of garbage patches to retain their structure & stability. For example, the South Pacific gyre is perhaps not as famed as its sister system to the north, but it is more stable and independent, since there are fewer routes for trash to leave that gyre and head to another. While the North Pacific gyre is less enduring by comparison, it collects more trash, which the researchers were able to trace to a specific location.

RELATED: Climate change linked to increases violence against women

“We identified a high-probability transition channel connecting the Great Pacific Garbage Patch with the coasts of eastern Asia, which suggests an important source of plastic pollution there,” said Miron.

Another highlight of the study is the discovery that the gyre in the Indian Ocean is weak, making it a poor place for garbage to accumulate. And overall, the connections between all subtropical gyres are weak, if existent to begin with. Miron says that in unusually intense winds, it’s more likely that subtropical ocean currents will blow trash toward land versus another system of currents in the ocean.

Pollution solutions

Though the researchers have yet to observe patterns of garbage patches in specific regions like the Bay of Bengal or Gulf of Guinea, the study still sheds light on the issue of plastic ocean pollution as a whole: where garbage starts, where it can end up, and what local governments and individuals can do about it.

Cleaning up an entire patch of garbage floating in the ocean would be a daunting, expensive and logistically challenging task, but Miron says that by looking at pollution routes, they were able to target sources of ocean cleanup besides the patches themselves. This makes the issue–and its potential solutions–much more accessible for all of us.

RELATED: Noise Pollution in the Ocean

Read More about Ocean Garbage Patches and Plastic Pollution

OCEAN PLASTIC MOUNTS DESPITE CLEANUPS

PLASTIC WASTE NECESSITATES POLICIES FOR PRODUCERS

THE US NEEDS A FEDERAL BAN ON MARINE PLASTIC POLLUTION

PLASTIC POLLUTION: AN EMERGING THREAT BENEATH OUR FEET

This study was published in the journal Chaos.

References

Miron, P., Beron-Vera, F. J., Helfmann, L., & Koltai, P. (2021). Transition paths of marine debris and the stability of the garbage patches. Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science, 31(3), 033101. doi:10.1063/5.0030535

Parker, D. (2013, July 11). Garbage patches: OR&R’S marine Debris Program. Retrieved March 28, 2021, from https://marinedebris.noaa.gov/info/patch.html

Featured photo of garbage on a beach by Joegoauk Goa.

About the Author

—Mackenzie Myers Fowler is a science writer, avid knitter, and former field station ragamuffin. She holds an MFA in nonfiction writing but would be a soil scientist if she could do it all over again. She lives in Michigan with her husband, her cat and a plethora of houseplants.