California’s Urban Forests Have Lowest Tree Cover per Resident

Valued at $181 billion, California’s urban forests cover 90.8 square meters (109 square yards) per city resident, the lowest of all US states.

California’s urban forests are not just a pretty sight; they are an asset valued at a whopping $181 billion, finds a new study. But, according to the study, the state’s urban tree cover at 90.8 square meters (109 square yards) per city resident is the lowest among all US states. The good news is that there are 236 million spots available for more trees to be planted.

The study finds that urban forests cover 15 percent of the urban area in California, consisting of 173 million trees that provide over $8 billion of services annually, from saving energy to removing pollutants in the air to increasing property values. But, with enough space to accommodate millions of more trees, Californians could enjoy greatly increased benefits. Existing trees are also facing the threat of diseases, invasive pests, climate change, and an increasing population.

For the first time, this study identifies the structure, function, and value of California’s urban forests to provide a baseline for managers in urban planning. In fact, these findings are currently being used by the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CAL FIRE) to identify priority areas for planting and to manage effective planting programs.

RELATED: Urban green spaces make cities happier

“Up to this point, we never really knew what the canopy cover was in different cities, what the predominant species were, and what the value of ecosystem services were,” says Greg McPherson, a research forester at the United States Forest Service’s Pacific Southwest Research Station located in Davis, California, and lead author of the study.

“Right now California’s urban forests are threatened by fire, invasive shot hole borer, and drought, and we don’t really know how much canopy we are losing because we’ve never had a baseline to compare it to.”

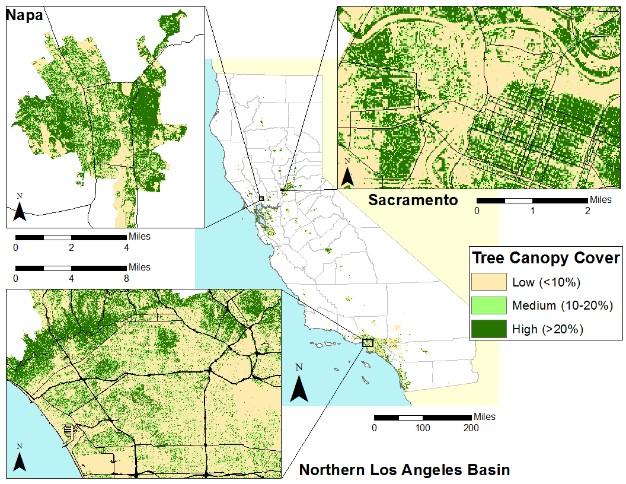

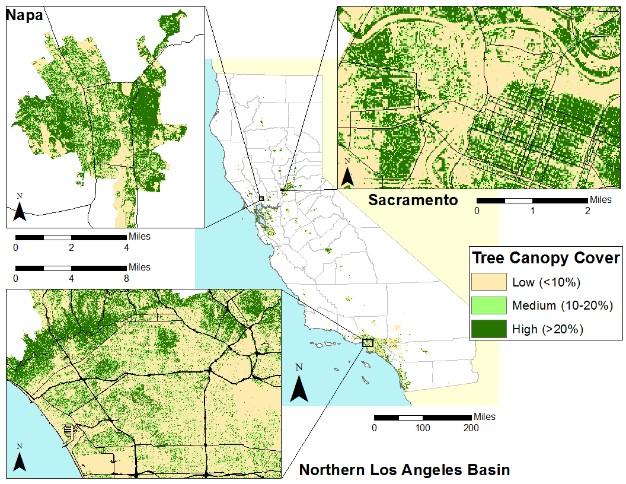

Data gathered from field plots totaling 3,796 trees across California was used to calculate tree population, density, and species composition covering six climate zones. This information as well as municipal street tree inventory data comprising 900,000 trees was incorporated into numerical models to estimate ecosystem services provided by urban trees. Urban canopy cover was mapped for six different landscapes at six different climate zones in California at a fine resolution of one meter and then compared with that of other states using a 2012 study that used satellite imagery.

“All previous studies used field data from plots, and they did not use any canopy mapping,” said McPherson. “This study is unique in that there is a geospatial component that takes the plot data and then translates it across the urban area so you can see what the relative values of benefits are spatially across the landscape.”

The coast of Northern California had the highest urban tree canopy cover followed by Inland Valley. Compared with other US states, California had the lowest urban tree canopy cover per resident at 90 square meters (109 square yards). The authors believe that this is because 20 out of 100 of the most densely populated cities in the US are found in California.

Across the state, half of the urban trees were young, and oak was the most common genus, comprising 22 percent of all trees, followed by cherry (6.6 percent), and then juniper (5.5 percent).

The benefits of urban forests

For every dollar spent on maintaining California’s urban trees, the return averages $2.52 in benefits such as saving electricity, removing carbon dioxide, and intercepting rainfall.

Urban trees save electricity used for air conditioning in the summer by providing shade to buildings, and during the winter, urban trees reduce the wind speed and help prevent cold air from entering homes and buildings.

Every year, urban forests save Californians the electricity usage equivalent to the amount required to air condition 210,280 households. Savings from cooling were greatest in the inland climate zones such as in the Southwest desert and Inland Valley where summers are particularly hot and dry.

Trees take up carbon dioxide—a greenhouse gas—from the atmosphere, thereby reducing global warming. The amount of carbon dioxide removed combined with emissions avoided by California’s urban forests is the equivalent to taking 1.8 million cars off the road.

RELATED: STREET TREES IN CALIFORNIA VALUED AT $1 BILLION

By intercepting rainfall, urban trees prevent excessive surface water runoff, particularly during storms. The rainfall intercepted by these urban forests is the equivalent to the amount of potable water consumed by almost half a million California households each year.

The threat of pests

Over the past few years, a new deadly pest, probably brought from Southeast Asia through increased global trade, has killed around a million trees in Southern California, according to anecdotal estimates.

The invasive shot hole borer is an ambrosia beetle (Euwallacea sp.) related to the tea shot hole borer from India and Sri Lanka, and it is smaller than a sesame seed.

By drilling tiny holes into trees, the beetle can transmit disease-causing fungi, which block the transport of water and nutrients from the roots to the upper parts of the tree, causing dieback—a condition in which the tree starts to die progressively from the tips of the branches and twigs.

“It’s spreading quite rapidly,” says McPherson. “It will infect a tree, it will use that tree, and it will reproduce in large numbers in a short period of time, and then it will kill the tree and then there will be millions of shot hole borers that will fly to several other trees.”

There are pesticides that can be sprayed to protect the trees, says McPherson, but they are expensive, and so can only be used on very valuable species.

A third of Southern California’s urban tree population as well as avocado and citrus groves faces the risk of infection. And the consequences could be catastrophic.

If half of the 23 million susceptible trees in Southern California cities succumb to disease, we would lose out on $616 million of services provided by the trees over a decade. What’s more, it would cost almost $16 billion to remove the dead trees and replace them with healthy ones of the same size.

Creating resilient urban forests

What’s clear is that many more trees need to be planted. But choosing which species to plant is tricky because many factors need to be considered to ensure the health and resilience of urban forests.

If a species is able to tolerate a wide variety of conditions such as varying levels of soil moisture and sunlight exposure, then it is more likely to adapt to changing future conditions than species that have a narrow range of tolerance, explains McPherson.

Species that can tolerate drought, emerging invasive pests, strong winds, and high salinity are suitable candidates for planting. In dry conditions, using reclaimed water for irrigation might be preferred, says McPherson, but reclaimed water is more saline than groundwater or river water.

Also, a greater diversity of tree species would limit the damage to trees by the aforementioned threats and ensure that forests are resilient. One of the diversity common goals states that a particular species should not comprise more than 10 percent of the population, and one genus should not represent more than 20 percent of the population. While oak accounted for 22 percent of the genera statewide, the authors say that its basal area (cross-sectional area of the tree trunk) was only 6.4 percent, reducing the impact it would have in the event of damage.

“We have identified promising trees that have not widely been planted, and we are testing those in trials in different climate zones around California,” adds McPherson.

—Neha is a freelance science writer based in Hong Kong who has a passion for sharing science with everyone. She writes about biology, conservation, and sustainable living. She has worked in a cancer research lab and facilitated science learning among elementary school children through fun, hands-on experiments. Visit her blog Life Science Exploration to read more of her intriguing posts on unusual creatures and our shared habitat. Follow Neha on Twitter @lifesciexplore.

References

McPherson, E. G., Xiao, Q., van Doorn, N. S., de Goede, J., Bjorkman, J., Hollander, A., . . . Thorne, J. H. (2017). The structure, function and value of urban forests in California communities. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening, (28), 43–53. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2017.09.013.