Marshall Islands Radiation Still Too High Decades Later

By Emily Rhode @riseandsci

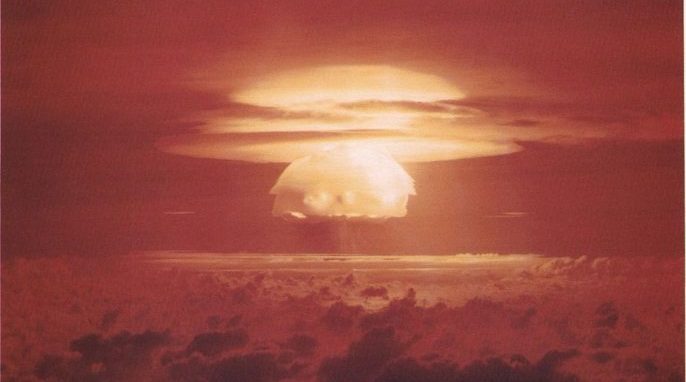

In the years immediately following the end of World War II, the United States government conducted large-scale testing of nuclear weapons on a small group of islands in the remote Pacific Ocean. On March 1, 1954, the largest nuclear device ever tested by the United States was detonated at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. Castle Bravo, as the bomb was known, created a mushroom cloud of radiation almost four and one-half miles wide. This was more than 1,000 times more powerful than the bomb dropped on Hiroshima. The size of the bomb, combined with a strong easterly wind and a delay in evacuations, caused exposure to radioactive fallout that led to serious health problems and birth defects for the island’s residents.

![Marshall Islands. Christopher Michel from San Francisco, USA (JJ7V2741.jpg) [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://magazine.scienceconnected.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/JJ7V2741_40325750-e1466450214805.jpg)

![Marshall Islands. Christopher Michel from San Francisco, USA (JJ7V2741.jpg) [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://magazine.scienceconnected.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/JJ7V2741_40325750-e1466450214805.jpg)

Residual Radiation

Over 90 percent of gamma radiation from nuclear testing comes from cesium-137. Cesium-137 has a half-life of 30.2 years, meaning that after 30.2 years, only half the original amount of radioactive material will remain. Based on estimates of the decay of cesium-137 from levels measured in the early 1980s, the US government concluded that the islands were once again inhabitable. More samples were taken in 1995 that confirmed this conclusion. The government of the Marshall Islands also conducted a separate study of the radiation levels, which showed similar results. In 1997 the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) took limited radiation measurements on Bikini Atoll. Once again, these results agreed with previous studies. At the time, the IAEA only recommended that people not resettle Bikini Atoll. Subsequent studies of the different islands suggested that in time, enough radioactive decay would occur to make all of them safe again for people. However, no new radiation measurements have been taken to test these predictions until now.

[tweetthis twitter_handles=”@riseandsci”]Radiation levels in Marshall Islands very high. Are residents safe?[/tweetthis]

A team of researchers from Columbia University traveled to the Marshall Islands to study current levels of gamma radiation in the areas most affected by bombs. They took measurements at six different islands in the atolls. They compared the levels of gamma radiation to levels found in an unaffected northern island as well as to New York City’s Central Park. The average radiation level in Central Park measures 100 millirems/year (mrem/y). This happens to be the same exposure level that the United States government and the government of the Republic of the Marshall Islands agreed to as “safe” during cleanup and compensation negotiations.

A Nuclear Legacy

What the researchers found was surprising. Levels of radiation on Bikini Atoll were far higher than estimated by previous studies. The average radiation level was 184 mrem/y. One measurement was as high as 648 mrem/y. The researchers believe that this is a result of the testing that occurred directly on Bikini Atoll. Rongelap Atoll, which received significant fallout from the testing but was not the site of a direct hit, showed measurements as high as 55 mrem/y. A 1994 study of gamma radiation on Rongelap Atoll predicted that the mean radiation level would only be 11 mrem/y as of 1995. The Columbia researchers found average radiation levels of 10.3 mrem/y in 2015. While these numbers might appear to be in agreement, radiation levels should have dropped significantly in the 20 years between the two studies. Despite extensive cleanup efforts by the US government on Enewetak Atoll, readings there still measured as high as 84.1 mrem/y.

On the island of Runit in the Enewetak Atoll, the researchers were very interested in looking at radiation levels around a giant concrete dome at the north end of the island. This dome is where the US government buried radioactive materials from the cleanup efforts on other islands. The researchers took readings at the base and top of the dome but could not get an accurate picture of the radiation given off, since they were only able to measure gamma radiation; the dome contains a large amount of plutonium-239, which only gives off alpha radiation. They believe that the alpha radiation emitted from the buried waste could be contributing to the overall radiation exposure of the people who inhabit Enewetak Atoll.

Hope to Return Home

The Columbia University researchers believe that numbers in the previous estimates of radiation levels should be called into question pending further studies. They believe that more research is needed to look at other pathways to exposure, such as food sources, before people are allowed to inhabit the affected islands again. Their hope is that future studies to determine the safety of the contaminated islands will allow those who now live in the crowded islands of Majuro and Ebeye to safely return to the Rongelap and Bikini Atolls.

References

http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2016/06/01/1605535113.full

http://majuro.usembassy.gov/legacy.html#_studies

http://www-ns.iaea.org/appraisals/bikini-atoll.asp

Emily Rhode is freelance writer and blogger whose training and passions lie at the intersection of science and education. She has worked as an outdoor environmental educator, a science teacher, and a professional communicator and trainer. You can follow her on Twitter @riseandsci.

GotScience.org translates complex research findings into accessible insights on science, nature, and technology. Help keep GotScience free: Donate or visit our gift shop. For more science news subscribe to our weekly digest.