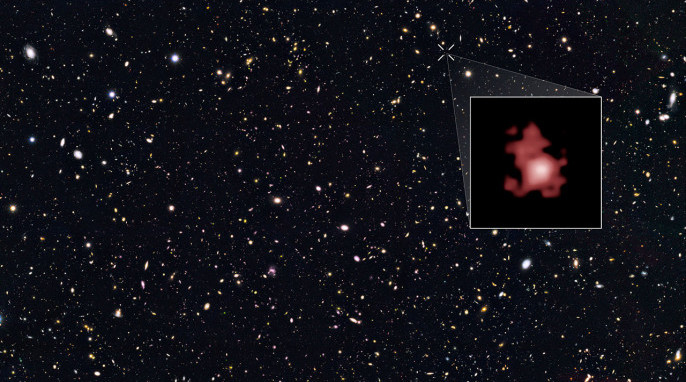

The Hubble Space Telescope has been conducting a deep-sky survey called “Great Observatories Origins Deep Survey North,” or GOODS North. The GOODS data has enabled astronomers to extend their view of galaxies back 150 million years further than any previously identified galaxy. The distant galaxy GN-Z11 was in the first generation of galaxies to form in the universe. Scientists estimate that it formed only 400 million years after the Big Bang. In fact, GN-Z11 formed at a time when the universe was mostly clouds of cold hydrogen gas.

“We managed to look back in time to measure the distance to a galaxy when the Universe was only three percent of its current age,” says Pascal Oesch of Yale University.

How Could Scientists Even Measure the Distance?

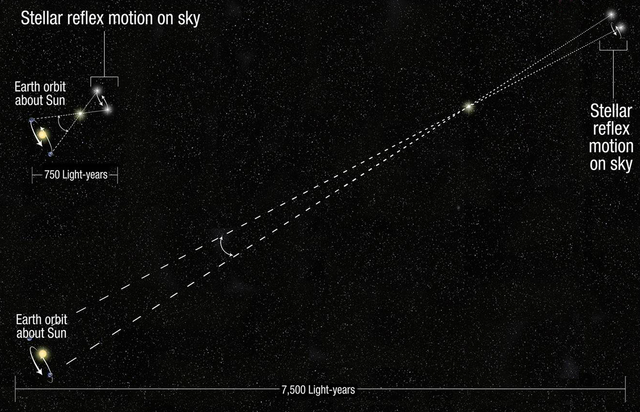

Astronomers have had to develop different methods to calculate the distance to objects. One method, called parallax, relies on careful observation and trigonometry to calculate the distance to another star. It’s a relatively simple method that involves taking two measurements at a known distance apart and comparing the angles. By measuring where a star is in December, and then again in June, scientists have a very large known distance to work with: the diameter of the Earth’s orbit. With precise timing and ultra-accurate measurements using the Hubble space telescope, it is possible to measure out to 10,000 light-years (a light-year is the distance that light travels in one Earth year: approximately 9.46 trillion km).

Space is big. Really big. You just won’t believe how vastly, hugely, mind-bogglingly big it is. I mean, you may think it’s a long way down the road to the chemist, but that’s just peanuts to space. —Douglas Adams, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

While 10,000 light-years sounds like a long distance, that’s only one-tenth the size of the Milky Way Galaxy. The Andromeda Galaxy, which is still visible to the naked eye, is 2.5 million light years away. Parallax can’t be used for such distances, so other methods had to be developed.

Being very resourceful, scientists came up with multiple methods involving the brightness and spectrum of a star. One standard measure involves using variable stars. Cepheid variable stars change in brightness in a known relationship to the pulsation period. This predictability makes it easy for scientists to determine how bright these stars are just by watching the period of their light curves. Cepheid variables can then be used comparatively to determine distances within the Milky Way and to “nearby” galaxies.

A similar method—but one which uses a very rare event—is to wait for a supernova to explode. Since scientists also understand how the light curve of a supernova develops, they can determine how far away a galaxy is. Supernovas are spectacularly bright events, which makes it possible to see them much farther away than Cepheids can be seen.

A General Approach: Splitting Light

While supernovas allow scientists to peer very deeply into the universe, there is no way to know where and when the next one will occur. To systematically study stars and galaxies, scientists need a method they can use more generally. Fortunately, taking a spectrum of a star’s light provides just such a method.

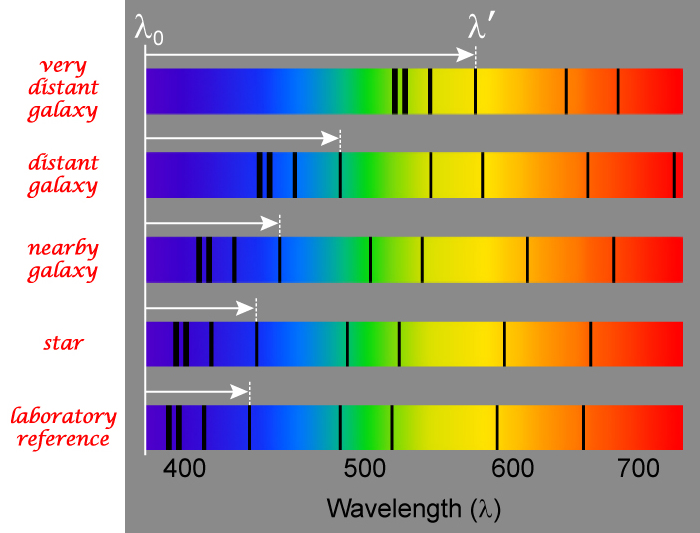

Groups of stars (globular clusters or galaxies) can also be measured using the spectrum obtained and comparing where certain emission lines or features are located with a reference spectrum. When objects are moving toward us they are shifted toward the blue end (higher frequency), and when they are moving away from us they are shifted toward the red end (lower frequency). Scientists refer to this measurement as a “redshift.” A good everyday analogy is to think about the sound an ambulance makes when coming toward you and how the sound changes by a drop in pitch after it passes.

When astronomers study objects over very large distances, the observed redshift may be enough that visible or even ultraviolet (sunburns!) light is shifted into the infrared (heat) or microwave part of the spectrum. To easily compare the shift, scientists use a shorthand Z-Number.

How Many Zs?

Hydrogen atoms have emission lines at specific frequencies which can be used to calculate the Z and thus the distance from us (or the time when the light was emitted). There is also a hydrogen emission line in the ultraviolet at 122 nanometers (nm) which is easy to spot in spectra obtained from galaxies. By determining where this emission line is in the observed spectrum of a particular object, astronomers can quickly determine how much it has shifted and calculate a Z-Number (see additional information below). Z-Numbers are used as a shorthand for the shift. They also allow astronomers to calculate the age of the universe at the time the light was emitted.

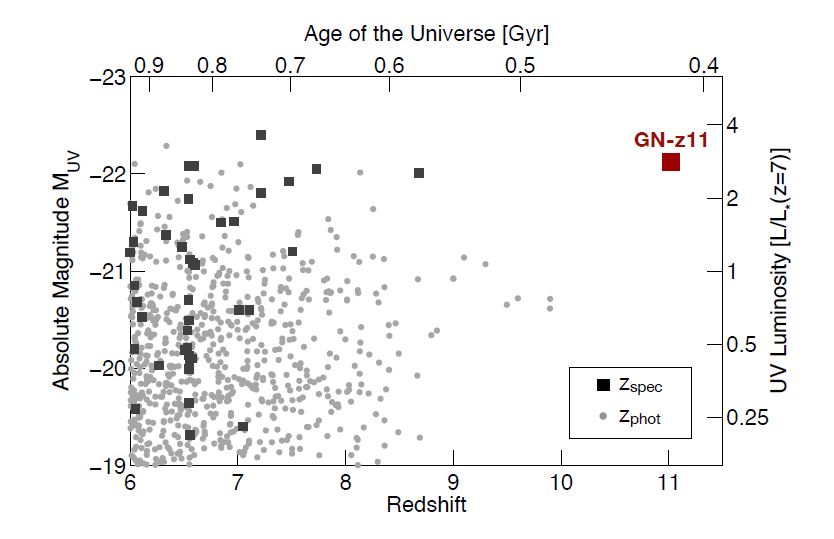

Z=0 means present time. The previous record holder for the farthest galaxy (EGSY8p7) had a Z=8.7 or ~13.1 Billion years ago. The GN-Z11 galaxy has a Z=11 which equates to ~13.3 Billion years ago.

What’s in a Name?

Are you wondering how the scientists came up with GN-Z11 as the name for the galaxy? GN comes from the GOODS North Sky Survey. We’ve just seen the Z11 part, which comes from the redshift.

Extraordinary Galaxy in Every Way

Not only is the GN-Z11 galaxy the oldest one we’ve ever found, 150 million years older than the previous record holder (EGSY8p7), but it is also a fully formed galaxy from a time when astronomers think the very first galaxies were just beginning to form. Additionally, GN-Z11 is beyond the range of what Hubble should be able to see. It was expected that only the future James Webb Space Telescope (launch date: October 2018) would be able to see such distant galaxies. GN-Z11 is so luminous, though, that even at this incredible distance the Hubble space telescope was able to obtain valid images and spectra at multiple wavelengths. Considering there are at least 100 billion galaxies in the observable universe, being the most distant by a significant margin is mind-boggling. The odds of winning the Powerball are much, much better, at only 292 million to 1.

As a reward for making it through the article, please enjoy a visual journey to GN-Z11 (in Ursa Major).

More from the Hubble Space Telescope

HUBBLE IMAGE OF JUPITER SHOWS NEW STORM BREWING

THIRTY YEARS OF THE HUBBLE SPACE TELESCOPE

Resources and Additional Information

Original Paper: “A Remarkably Luminous Galaxy at Z=11.1 Measured with Hubble Space Telescope Grism Spectroscopy” (Oesch et al. 2016)

Hydrogen Emission Lyman-Alpha Line (121.567 nm)

Hubble/NASA Lyman alpha and Lyman break galaxies Excellent discussion and graphics for those wishing to better understand the Lyman Alpha line and the Lyman break as used in measuring galaxies.

Number of Galaxies in the Universe

How are Z-Number calculations made?

Let’s assume the band we want to measure is emitted at 122 nanometers (nm) in the laboratory or as measured from the sun. If we measure a galaxy where this band is redshifted to 366 nm, then we can say the galaxy is Z=2. The formula is:

Z = (measured wavelength – lab wavelength) / lab wavelength

… which in our example is:

Z = (366 nm – 122 nm) / 122 nm = 244 nm / 122 nm = 2

Now you have a Z-Number!

Your Z-Number doesn’t just tell you how much the light has been shifted; it also will tell you the time when the light was emitted. Those calculations are a bit more involved, so here’s a handy calculator (choose flat universe).

Some examples:

Z=0 ~now

Z=2 ~10.4 Billion years ago << we calculated this Z above

Z=8.7 ~13.1 Billion years ago << galaxy EGSY8p7 (second-oldest in the universe)

Z=11 ~13.3 Billion years ago << galaxy GN-Z11 (oldest in the universe)