By Neha Jain

@lifesciexplore

Fecal Fungi May Lead to Cheaper Biofuel

Manure may be a good fertilizer, but there’s more to manure than you think. Scientists have harnessed gut fungi from herbivore feces that can easily digest tough plant components in wood, algae, and grasses into sugars, which can then be fermented to produce biofuel and other bio-based products.

Biofuel producers are faced with a problem: They are unable to fully break down plant materials into sugars because of the tough-to-digest components of plant cell walls. Herbivores, however, have been digesting these tough materials for millions of years, thanks to fungi housed in their guts.

From the manure of goats, horses, and sheep, researchers isolated fungi that are capable of producing hundreds of diverse enzymes—proteins that can break down large molecules—that work together to degrade crude, untreated plant matter in the absence of oxygen. These gut fungi, the researchers claim, perform just as well in breaking down plant materials into sugars as the best fungi varieties engineered by industry. And with further tweaking, the gut fungi can outperform commercially used fungi.

Biofuel Tough Guys

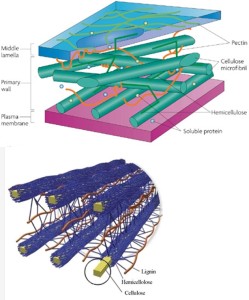

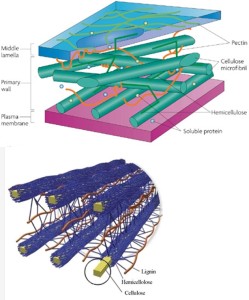

Lignin, cellulose, and hemicelluloses—together called lignocelluloses—are long chains of molecules called polymers found in plant cell walls. They comprise a large proportion of the dry weight, or biomass, of plants. Cellulose is composed of long chains of the sugar glucose. Lignin and cellulose give wood and bark their characteristic strength and rigidity; they are responsible for the fiber in plant-based foods. Lignin makes some vegetables crunchy, such as carrots. Both cellulose and lignin provide structural support to plant cells and are the most abundant polymers on Earth. Hemicelluloses are formed by long chains of sugars, which include glucose as well as other sugars such as galactose and mannose. Hemicelluloses, together with pectins, bind to cellulose in the cell wall by forming a network of cross links. The gaps in the cell wall are filled by lignin.

Upper: Primary cell wall consists of cellulose microfibrils cross-linked to hemicelluloses and pectins (Sticklen 2008).

Lower: Cellulose microfibrils surrounded by hemicelluloses and lignin (Doherty et al. 2011).

Lignin needs to be removed from crude biomass so that cellulose and hemicellulose can be broken down to release the energy-rich sugars. Because lignocelluloses are hard to digest, biofuel producers have to pretreat them with either heat or harsh chemicals, both of which are costly. Sometimes producers end up discarding the biomass altogether.

Two industrially engineered fungi—Trichoderma reesei and Aspergillus nidulans—produce only a small number of enzymes and are unable to digest even pretreated lignocelluloses into sugars.

Fantastic Feces

After collecting manure samples, scientists decoded the messenger RNA transcripts—molecules that carry the code for making proteins in cells, some of which are enzymes—to give the transcriptome, which represents all the possible proteins that the fungi could produce. Since only a small fraction of proteins are enzymes, the researchers needed to identify which proteins could be the ones that degrade plant biomass. To find out, they created a map of all the proteins that the fungi actually make—known as the proteome—and used it to home in on the biomass-degrading enzymes. They found that 2 percent of the transcriptome coded for these enzymes.

The researchers discovered that the gut fungi can produce hundreds of enzymes capable of tackling different materials, compared with industrial fungi, which produce only a maximum of 100 enzymes. “Nature has engineered these fungi to have what seems to be the world’s largest repertoire of enzymes that break down biomass,” says Michelle O’Malley, senior author of the study and professor of chemical engineering at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

In addition, the fungi possess a wealth of enzymes able to degrade hemicelluloses. Compared with Aspergillus used in industry, the anaerobic gut fungi are 300 percent more effective at degrading xylan, a type of hemicellulose made of the sugar xylose. By degrading the outer layer of hemicelluloses and pectins that surround cellulose, cellulose-degrading enzymes are able to get access to the energy-rich cellulose. What’s more, the fungi are highly versatile: They can swiftly adapt to produce enzymes that can break down whatever material scientists feed them—grass, wood in the form of cellulose powder, or filter paper.

“Because gut fungi have more tools to convert biomass to fuel, they could work faster and on a larger variety of plant material. That would open up many opportunities for the biofuel industry,” says O’Malley.

These gut fungi may eliminate the need for companies to pretreat the plant biomass with expensive processes. Without the pretreatment, cheaper biofuels and other bio-based products may be possible in the future.

This study was published in the journal Science.

References

Sticklen, M. B. (2008). Plant genetic engineering for biofuel production: Towards affordable cellulosic ethanol. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9, 433–443.

Doherty, W. O. S., Mousavioun, P., and Fellows, C. M. (2011). Value-adding to cellulosic ethanol: Lignin polymers. Ind. Crop. Prod. 33, 259–276.

GotScience.org translates complex research findings into accessible insights on science, nature, and technology. Help keep GotScience free! Donate or visit our gift shop. For more science news subscribe to our weekly digest.