Ocean and climate changes are affecting us and all living things.

The Biota Project Blog

Written by Helen Cheng (@ms_helenc / @thebiotaproject)

June 8th is World Oceans Day. It’s a day where we celebrate our vibrant oceans and all the resources they bring us. But it shouldn’t be one day that we value our oceans. Oceans form the foundation of the blue planet on which we live. They cover 71% of our planet’s surface [1] and they are a life-support system for Earth, providing us with things that are vital for us to live from the food we eat to the oxygen we breathe.

The oceans also regulate the global climate; they mediate temperature and drive the weather, determining rainfall, droughts, and floods. They are the world’s largest store of carbon, storing 50 times more carbon than the atmosphere [2].

But the interaction between these two natural forces of ocean and climate is altering, and the exchange is intensifying. We’re seeing the consequences of this around the world. In the last 200 years, the oceans have absorbed a third of the carbon dioxide (CO2) produced by human activities and 90% of the extra heat trapped by the rising concentration of greenhouse gases [3]. Because of this, it is affecting the way we and all living things live.

RELATED: POLAR BEARS ARE STRUGGLING TO FIND FOOD

Oceans and Acidification

The basic chemistry of oceans is changing faster now than has over the past 65 million years [4]. The ocean absorbs vast quantities of heat as a result of increased concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, mainly from fossil fuel consumption. The Fifth Assessment Report published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 2013 [5] revealed that the ocean had absorbed more than 93% of the excess heat from greenhouse gas emissions since the 1970s. This is causing ocean temperatures to rise. The continual absorption of CO2 through carbon emissions like that from vehicles, construction, and humans, increases acidity levels, and—when combined with the warming of our oceans—the ecosystems that rely on calcification like shellfish beds and coral reefs grow weaker and are dying off. Without these vital ecosystems and habitats, they can no longer offer a healthy ocean habitat for the species that rely on them for food and protection, thus creating a negative cascade. Scientists estimate if the current rates of temperature increase continue the oceans will become too warm for coral reefs by 2050.

Oceans and Extreme Weather

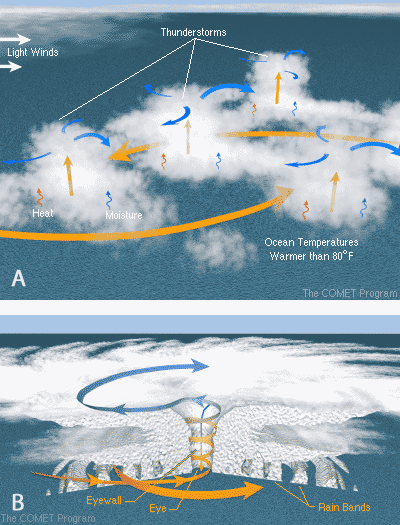

These warming waters influence the flow and process of extreme weather. Take the formation of storms and hurricanes, which we wrote this blog post about during the hurricane season of 2019 . The effects of warming waters can cause extreme weather like heat waves, droughts, strong storms, heavy snow and frigid temperatures. How can oceans cause such random and, sometimes, erratic weather patterns? Because of absorbing CO2, the ocean is very effective at absorbing and storing heat. These two factors of absorption and storage play a big role in how the ocean affects our weather. For example, because the ocean releases heat more slowly than land, coastal areas tend to be more temperate. Upwelling in many coastal regions, such as California, provides a cool contrast in air temperature over the ocean and land that is conducive to frequent summer fog. In addition, high-pressure areas can form where the air is being heated by the sun (from the above) and by the ocean (from below), which makes winds stronger.

RELATED: OCEAN ACIDIFICATION THREATENS SHELLFISH

However when there is too much CO2 and heat, the system becomes off-balance. Warm ocean waters provide the energy to fuel storm systems. Tropical storms form over warm ocean waters, which supply the energy for hurricanes and typhoons to grow and move, often over land. More CO2 from increased greenhouse gas emissions is being absorbed by the ocean, which can creating warmer oceans. Warmer oceans means stronger and more frequent storms.

Data from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) [6] show that the average global sea surface temperature – the temperature of the upper few meters of the ocean – has increased by approximately 0.13°C per decade over the past 100 years. Additionally, it has also been discovered that the deep ocean has also absorbed with one third of the excess heat [7]. The IPCC’s 2013 Report predicts that there is likely to be an increase in mean global ocean temperature of 1-4°C by 2100.

All of this threatens food security with growth or decline of crops and food, increases in the prevalence of diseases, and results in the loss of coastal protection due to extreme weather events.

RELATED: UNDISCOVERED SPECIES OF THE DEEP SEA: CAN WE FIND THEM?

Oceans and Coastal Flooding

The two major causes of global sea-level rise are: 1) thermal expansion caused by warming of the ocean and 2) increased melting of land-based ice. With continued ocean and atmospheric warming, sea levels will likely rise for many centuries at rates higher than that of the current century. In the United States, almost 40 percent of the population lives in relatively high-population-density coastal areas, where sea level plays a role in flooding, shoreline erosion, and hazards from storms [8].

Major cities, New York City, Miami, San Francisco even international cities, are vulnerable to sea level rise and flooding. NOAA forecasts that the U.S. North Atlantic and in places like New York City and Boston will experience more days of tidal flooding – flooding that happens due to extremely high tides regardless of storms. They forecast that the number of days of flooding in this region would increase by about 140% [9]. Water on the streets, damages in the form of mold and erosion of critical and aging infrastructure, as well as cause public inconveniences, stress, and anxiety. But how do you stop the ocean? Many coastal communities are grappling with this challenge.

The Great Lakes are included!

What about the Great Lakes? Because weather patterns have changed and become extreme, these trends are impacting the Great Lakes region. Extreme rainfall events have increased over the last century, and these trends are expected to continue. Combined with land cover changes due to development, increased precipitation has and likely will continue to lead to flooding, erosion, declining water quality, and negative impacts on transportation, agriculture, human health, and infrastructure.

One of the biggest issues that post a risk to the Great Lakes includes harmful blooms of algae. The culprits behind harmful algae blooms (HABs) are a combination of high nutrient pollution – nitrogen and phosphorus, which stimulate the growth of algae and high water temperatures linked to climate change. Because of HABs, it impacts beach tourism in the Great Lakes and drinking water supply to the communities surrounding the Great Lakes. [10]

The Good.

At-risk communities across the country are becoming more vulnerable to climate change impacts such as flooding, drought, and extreme heat, especially in urban areas. For example, tribal nations are especially vulnerable because of their reliance on threatened natural resources for their cultural, economic and vital needs [11]. Integrating climate adaptation into planning processes offers an opportunity to better manage climate risks now. Developing knowledge for decision making in cooperation with vulnerable communities and tribal nations will help to build adaptive capacity and increase resilience.

We as one Earth have started in the direction of addressing climate change. More than 60 countries say they will zero out carbon emissions [12]. World leaders gathered in Paris in 2015 to work together in drafting the next steps to act responsibly on climate change. Called the Paris Agreement, this environmental accord calls to address climate change and reduce its negative impacts. The Paris Agreement calls on countries to substantially reduce global greenhouse gas emissions in an effort to limit the global temperature increase in this century to 2°C above pre-industrial levels, while pursuing means to limit the increase to 1.5°C [13]. There are also national, regional, local organizations that have and will continue to actively participate in these climate negotiations, urging leaders, businesses, and communities to take the necessary steps to save our planet. However, there is still so much work, especially to get ALL countries and nations to get on-board.

As we celebrate World Oceans Day, let us take a moment to celebrate the ocean and how intertwined we are to the oceans regardless of where we live. We go to the beach, we eat its fish, the ocean regulates the weather, it gives us oxygen; the ocean provides so much us, let us do our part to help it not only directly but also indirectly in the ways of reducing pollution and carbon emissions. Because it affects us all.

Learn more about World Oceans Day and how to take part in the campaign visit https://worldoceansday.org/

Featured photo: Rocky coastal intertidal of Maine, USA. Photo Credit to Helen Cheng.

References

(1) https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/exploration.html

(2) https://science.nasa.gov/earth-science/oceanography/ocean-earth-system/ocean-carbon-cycle

(3) https://www.worldwildlife.org/stories/how-climate-change-relates-to-oceans

(4) Ridgwell, A. and Schmidt, D.N., 2010. Past constraints on the vulnerability of marine calcifiers to massive carbon dioxide release. Nature Geoscience, 3(3), pp.196-200.

(5) IPCC 2013 Fifth Assessment Report https://www.ipcc.ch/assessment-report/ar5/

(6) https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/cag/global/time-series/globe/ocean/ytd/12/1880-2017

(7) Levitus, S., Antonov, J.I., Boyer, T.P., Baranova, O.K., Garcia, H.E., Locarnini, R.A., Mishonov, A.V., Reagan, J.R., Seidov, D., Yarosh, E.S. and Zweng, M.M., 2012. World ocean heat content and thermosteric sea level change (0–2000 m), 1955–2010. Geophysical Research Letters, 39(10). https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1029/2012GL051106#support-information-section

(8) https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/sealevel.html

(9) https://tidesandcurrents.noaa.gov/HighTideFlooding_AnnualOutlook.html

(10) Synthesis of the Third National Climate Assessment for the Great Lakes Region http://glisa.umich.edu/media/files/Great_Lakes_NCA_Synthesis.pdf

(11) https://toolkit.climate.gov/topics/tribal-nations

(12) https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/09/25/climate/un-net-zero-emissions.html

(13) https://www.nrdc.org/stories/paris-climate-agreement-everything-you-need-know