Read how immune cells are like fighters on the planet Dune, and how this defense system changes for sepsis survivors.

By Elisa Huertas Ciorraga

Why do people who have survived sepsis get infections more easily? That was the question researchers from the Immunology and Microbial Disease Department of Albany Medical College wanted to answer.

Sepsis is a life-threatening medical condition that happens when our body reacts extremely to an infection or an injury. The immune system causes inflammation and the blood functions start to fail. If not treated quickly, it can lead to serious problems in tissues, organs failing, and death. This new research from Albany Medical College can help us understand why sepsis survivors have a weaker immune system, why they get infections more easily, and how to help them.

As explained further below, the researchers found that the answers were in the messages that different parts of the immune system send each other. Their study showed that the immune system of mice sepsis survivors cannot respond to the signaling of a protein called G-CSF. The result is insufficient production of certain immune cells that help fight infections. For that reason, mice are more vulnerable when facing microbes in the future.

Immune system and sepsis survivors

Almost any type of infection can lead to sepsis. In the U.S. alone, the CDC estimates that 1.7 million adults have sepsis each year; 350,000 of them die or move to hospice, and many people who survive it need to be readmitted to hospital and might need surgeries or medication in the future.

RELATED: Ant-ibiotics: How Ants Treat Infections

When we have an infection, our immune system fights it using inflammation, defense cells, and signaling proteins. This also happens during sepsis, but the body’s response is so strong that the immune system in sepsis survivors no longer works as before. Why? That is what researchers wanted to find out.

To understand how the fighters within the immune system work and communicate between them, let’s use the world of Dune.

Dune and the immune system

Our body is like a planet, with many different cities (organs) connected through our blood vessels. And, as it happens in Dune, outsiders can attack us using different spaceships. In our body, outsiders can be bacteria, viruses, fungi, parasites, and other microbes that have different shapes and languages.

The planet must be protected. Some of its defenses are the climate and sandstorms that protect from outsiders, similar to our planet (our body) when we sneeze or cough to get rid of microbes. Dune has high temperatures, like when we want to kill bacteria or viruses with a fever. And it also has the defense force—in our case, the immune system.

Allow me to introduce you to some of the fighters

Immune cells are born in the bone marrow, a special tissue inside our bones. Here, blood stem cells, a special type of cell that can transform into different blood cells, live and change.

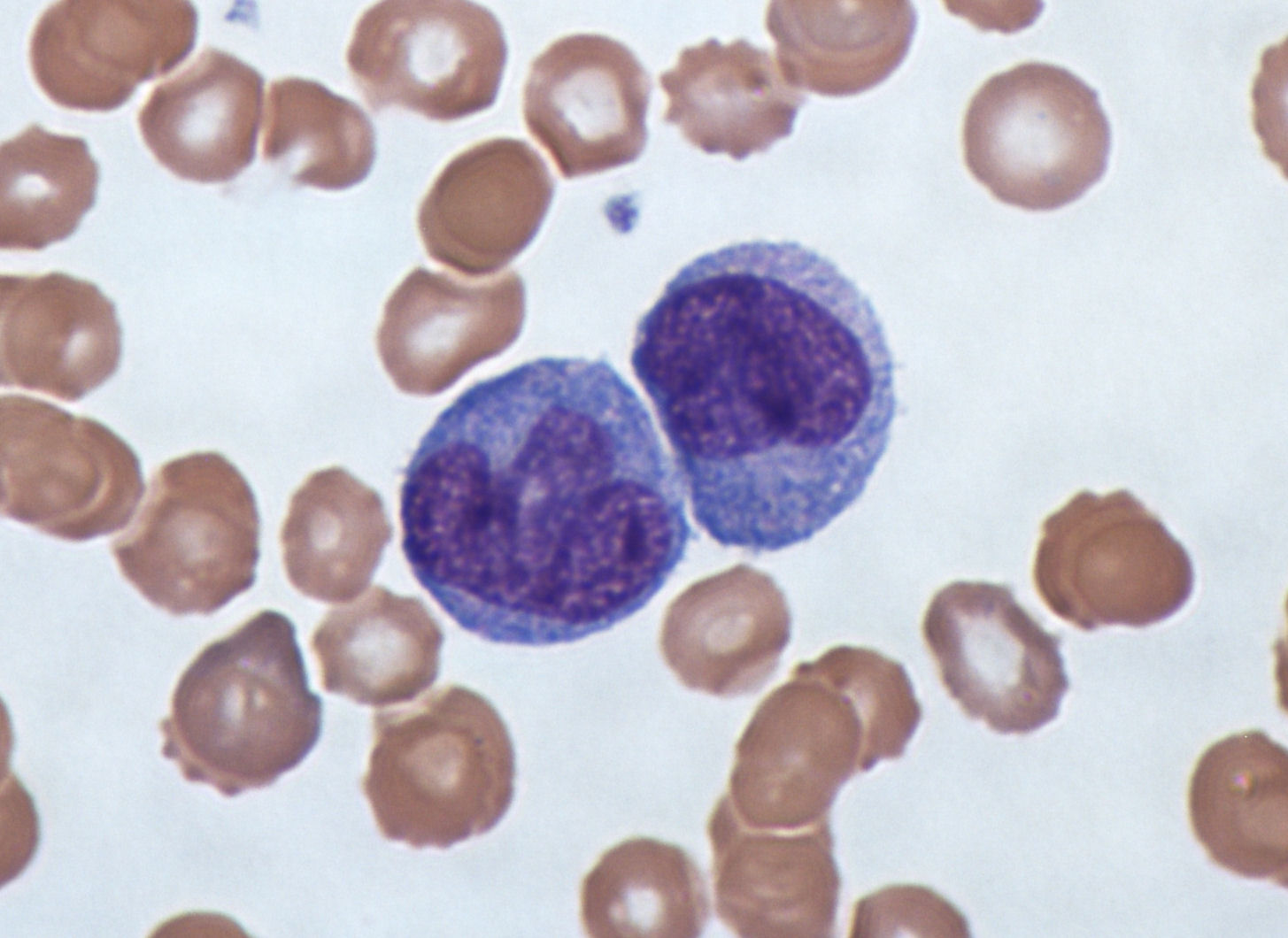

Our blood contains different types of blood cells: red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets. The white blood cells, or leukocytes, are the immune system fighters. But not every fighter uses the same tactics. The same happens with the immune cells.

To become a fighter, there are two different trainings to specialize in particular defense tactics. Two different blood stem cells can transform into white blood cells: lymphoid stem cells (that produce lymphocytes and monocytes) and myeloid stem cells. The myeloid stem cell can transform into three different types of cells: neutrophils, basophils, and eosinophils. This change or differentiation is called myelopoiesis, which is tied to sepsis. The researchers studied sepsis by taking a closer look at these three types of fighters.

If you have seen Dune, you know that part of the planet’s defenses are the worms. Big creatures that swallow the outsiders. Taking this idea from the Arrakis planet to our immune system, we have the macrophages, which literally means “big eater.” Macrophages are immune cells that protect us by eating outsiders.

And remember that our immune system not only attacks outsiders; it can also attack our own fighters, like in autoimmune diseases, as well as traitors, such as cancer cells, which come from our own body but have become dangerous for us.

But coming back to the worms. How are they summoned? By thumpers. A device that plays a rhythm, a signal for them. Well, like worms, macrophages (and the other immune cells) also respond to signals. One of those signals is a protein called G-CSF.

Sepsis and signaling proteins

The researchers wanted to understand why sepsis survivors are more vulnerable to infections. They did an experiment with three groups of mice: healthy mice, a control group that had had a placebo surgery, and mice that had survived sepsis. To provoke sepsis in this third group, they pricked the mice’s intestines, allowing microbes to leave the bowels and enter the blood—and therefore cause sepsis.

To compare the three groups, the researchers analyzed blood and bone marrow samples from each group on days 1, 3, and 5 after surgery. Then they studied blood, bone marrow, and spleen samples at day 20, when the mice that had survived sepsis (yeah, some of them died) no longer had an infection.

They saw that, in mice that were experiencing sepsis, emergency myelopoiesis happened in the bone marrow. That is, blood stem cells started training in the headquarters to become fighters and defend the body from the infection in the blood. These mice also had more white blood cells in the blood. The numbers of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets changed in sick mice. All of that is normal.

However, after sickness, the researchers saw that the immune system of sepsis survivors was weaker than before. Some long-lasting changes happened in the bone marrow (where the blood cells do their training), in the blood, and in the spleen, a very important organ where, among other things, immune cells can be produced.

RELATED: Nanoparticle Vaccine Created for Better Immune Response

Why sepsis survivors respond differently

One of the changes in the immune system of sepsis survivors was that there were more monocytes and neutrophils in the blood and the bone marrow. But the neutrophils were not ready to fight; they weren’t fully functional. Besides, there were way fewer macrophages (the big eaters we compared to Dune’s worms) in the blood.

The researchers continued to investigate why mice sepsis survivors had fewer macrophages in their blood; they found that the problem was in the signaling from protein G-CSF (the thumpers).

That signaling protein, G-CSF, is a cytokine, a messenger that is released during infections caused by bacteria due to inflammation. Its job is to tell blood stem cells to start training (differentiate) and move to the blood (mobilization) to fight the infection. This process of training and mobilization of blood stem cells is called hematopoiesis (hemato– means blood and –poiesis means production). This process is impaired in sepsis survivors. Immune cells are no longer able to train and mobilize properly, as before the sickness, so they cannot fight outsiders as effectively.

The researchers think that stem blood cells after sepsis are not able to respond appropriately to G-CSF, as the cell levels are normal. Meaning that there are enough thumpers but they don’t work and send their message. That causes immune suppression, and it might be why sepsis survivors can get infections more easily.

This study brings new opportunities to research further into treatments for sepsis survivors, which could lead to a higher quality of life.

RELATED: Cells Use mRNA and Protein Synthesis to Fight Infection

How do I identify sepsis? Who is at risk?

One of the best ways to prevent sepsis is to prevent infections. This applies to many things, from meningitis to COVID-19, hygiene to vaccines. Washing our hands with water and soap, keeping wounds clean, and taking care of chronic diseases (including diabetes) are all important practices.

A person experiencing sepsis following an infection may have one or more of the following symptoms and signs:

- The heart rate and pulse are not normal, such as a high heart rate or a weak pulse.

- The person has shortness of breath.

- The person has a fever, is shivering, or is feeling very cold.

- The person’s skin is clammy or sweaty.

- The person is disoriented or confused.

- The person feels extreme pain or discomfort.

People with suspected sepsis should seek emergency medical assistance.

Who is more at risk of sepsis?

- Adults older than 65 years old.

- Children younger than 1 year of age.

- People with a weaker immune system.

- People who have had sepsis already.

- People with chronic medical conditions, that is, long-term conditions such as cancer, diabetes, lung diseases, or kidney diseases.

- People in hospital or with serious diseases.

This study was published in the peer-reviewed journal Stem Cell Reports.

The information contained in this article is for informational purposes only and is not intended as health or medical advice. Always consult a physician or other qualified health provider regarding any questions you may have about a medical condition or health objectives.

References

Biswas, N., Bahr, A., Howard, J., Bonin, J. L., Grazda, R., & MacNamara, K. C. (2024). Survivors of polymicrobial sepsis are refractory to G-CSF-induced emergency myelopoiesis and hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell mobilization. Stem Cell Reports, 19(5), 639–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stemcr.2024.03.007

NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms. (n.d.). White blood cell. National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/white-blood-cell

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, March 8). About sepsis. https://www.cdc.gov/sepsis/about/index.html

U.S. National Library of Medicine. (n.d.). Sepsis. MedlinePlus. https://medlineplus.gov/sepsis.html

National Institute of General Medical Sciences. (2023, September). Sepsis. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.nigms.nih.gov/education/fact-sheets/Pages/sepsis.aspx

Featured image “File:Monocytes, a type of white blood cell (Giemsa stained).jpg” by Dr Graham Beards is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

About the Author

Elisa Huertas is a science communicator who loves music, reading, and the Lord of the Rings. She studied a master’s in science communication and journalism and has an academic background in nutrition. She is Spanish but she lives in Ireland with her husband and daughter. Connect with Elisa via her website or follow her on Instagram and TikTok @elisadivulga.