By Angie Lo

Fiber is important. Aside from its well-known roles in preventing constipation and lowering blood sugar, fiber has yet another vital function— boosting the body’s immunity. When fiber gets consumed and enters the digestive tract, some of it can get broken down into smaller molecules known as short-chain fatty acids. Also called SCFAs, these molecules have the ability to communicate with the cells of the immune system. This results in these cells having improved function, bettering their power to protect against bacteria.

But how exactly does this communication process work, and why does it lead to increased immune function? At Keio University in Tokyo, Japan, a team of researchers decided to find out precisely that.

A method that sticks

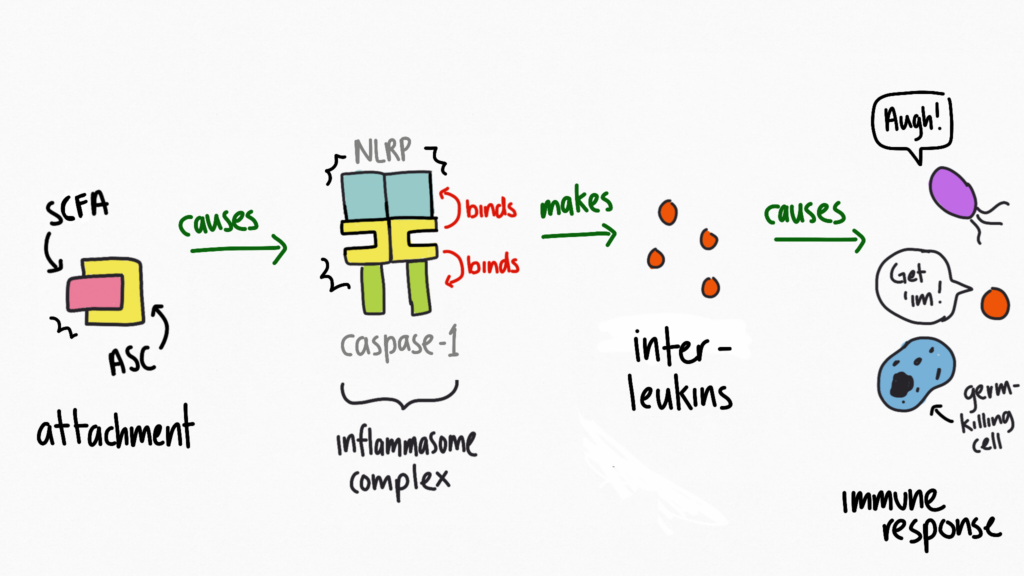

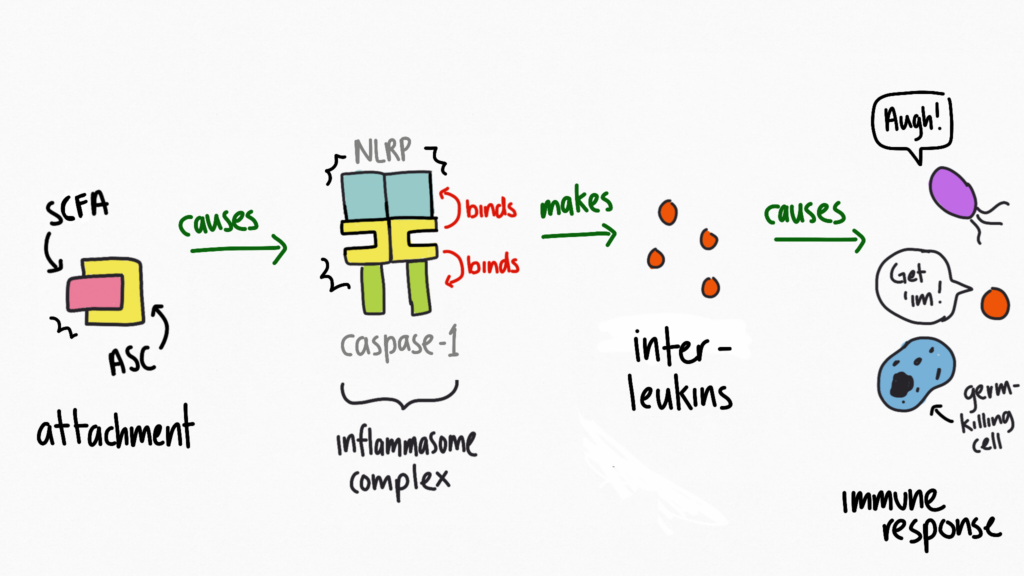

Molecules often communicate by attaching themselves to a specific cell component. When attachment occurs, this signals the cell to carry out certain activities that result in an outcome— in this case, the warding off of bacteria.

However, in the case of fiber-derived SCFAs and immune cells, it’s not well known what specific activities occur, and what role they play in fighting invasive germs. Researchers at Keio University decided to tackle this mystery by looking at the first step in communication. If they could figure out which cell part SCFA binds to, it might provide some clues about the processes it signals.

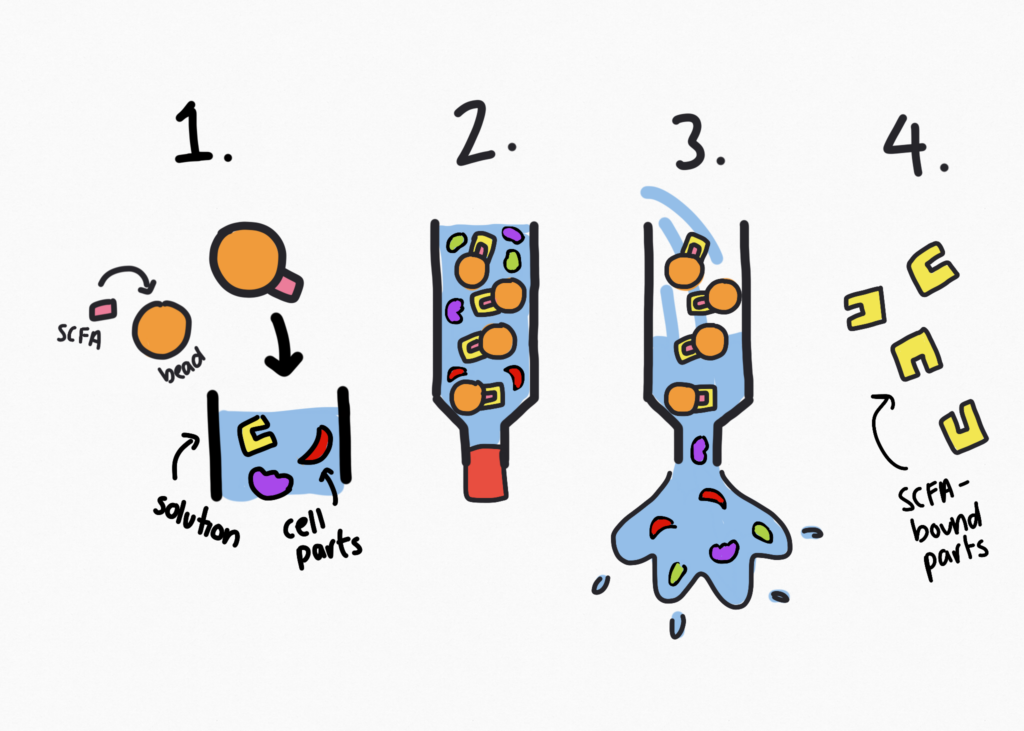

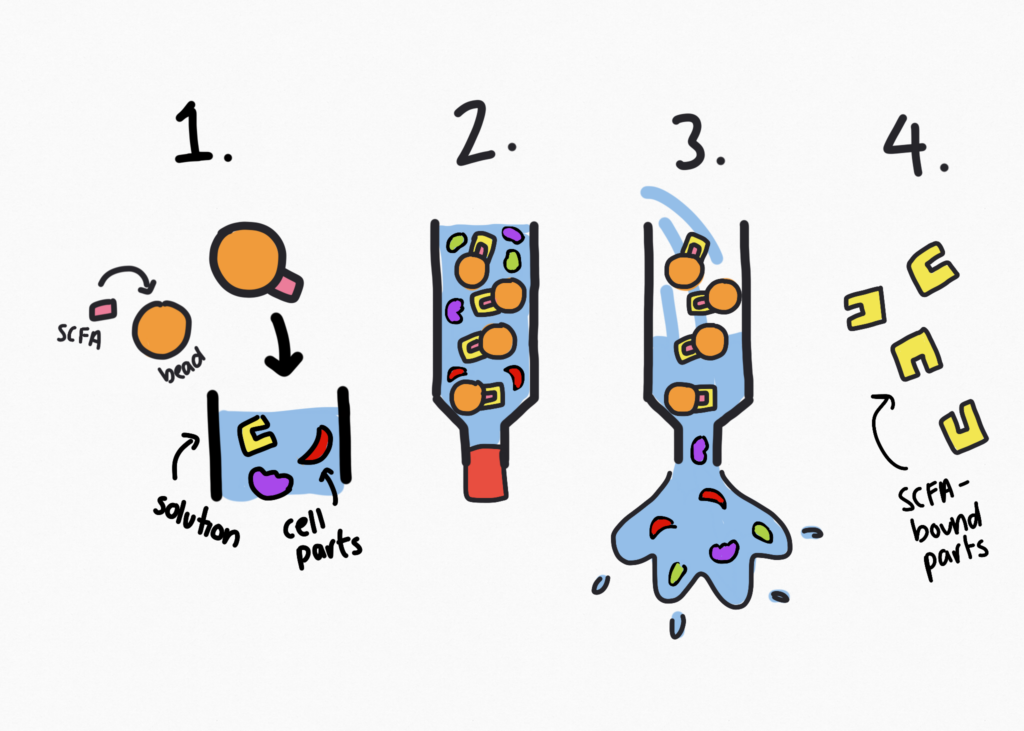

In order to do this, a method called affinity purification was employed. In this process, researchers attached SCFA molecules onto the surface of microscopic beads. These beads were then placed in a special solution containing various components of immune cells. Over the span of several hours, the SCFAs on the beads came into contact with, and subsequently attached to, their specific cell parts in the solution.

Afterwards, researchers thoroughly rinsed the beads with another liquid. This caused loose immune cell components to be washed away from the beads— leaving only the cell parts tightly bound to the SCFAs. The researchers were then able to purify these remaining parts, isolating them for further study.

By studying its characteristics, researchers could then determine the exact identity of the part to which SCFA binds. They subsequently discovered that SCFA attaches to a small protein on immune cells called ASC— solving the first part of the communication mystery. With one step of the puzzle now complete, researchers then sought to find out even more about the newfound SCFA-ASC interaction.

SCFAS in action

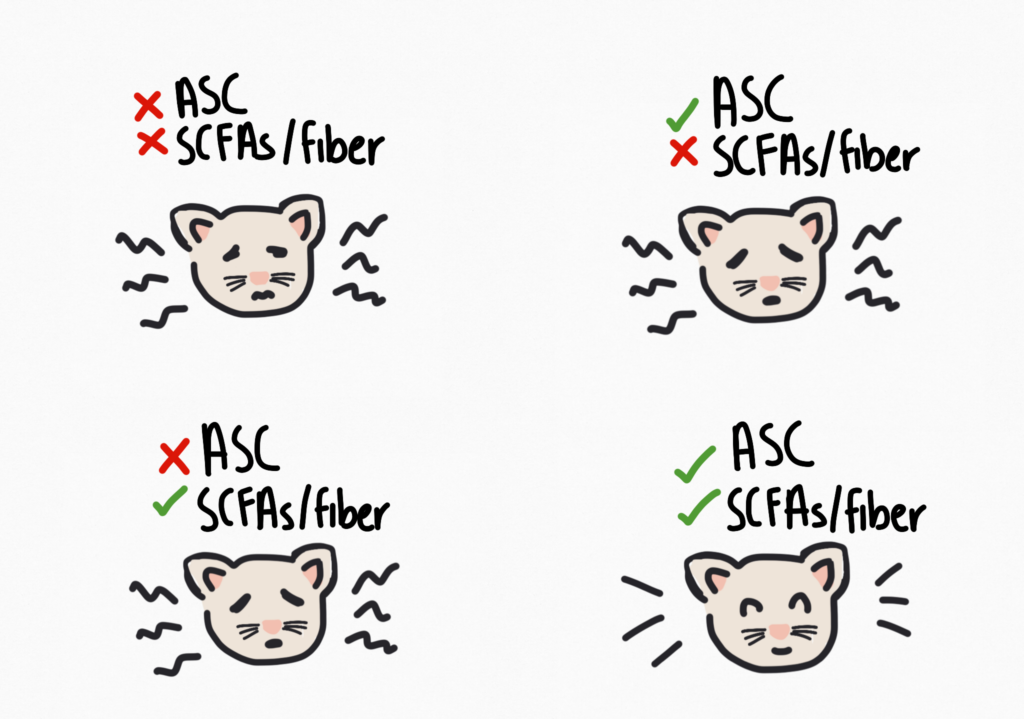

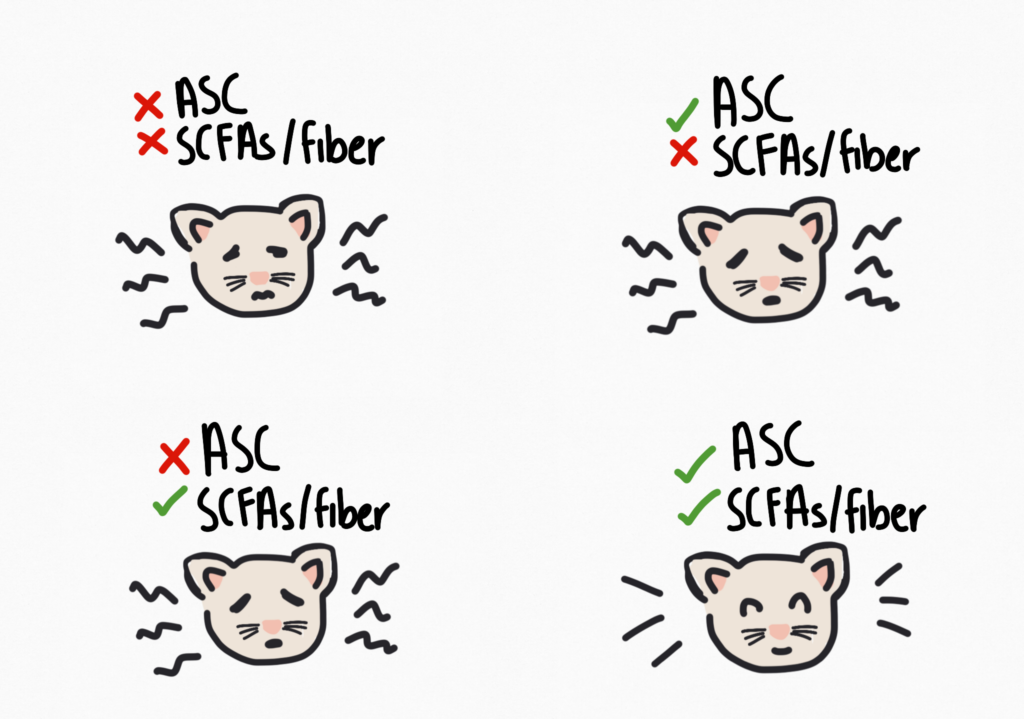

Researchers first decided to examine how this interaction translated in real life . In order to do so, they studied a group of young mice. Some mice had the ASC protein in their immune cells, however; others had a special genetic variant that prevented ASC from being present. These mice were then randomly divided into two smaller groups. One group of mice were given a diet enriched with SCFAs or dietary fiber, while the other group were not.

Researchers then found that when exposed to bacterial infections, mice who had ASC and consumed SCFAs or fiber had better responses to infection than any of the other mice. Additionally, it was discovered that these mice had much lower amounts of bacteria in various internal organs. This confirmed that fiber-derived SCFAs and ASC work together to ward off germs in organisms, inducing protective processes that neither alone could achieve.

Unlocking new steps

Researchers then looked towards the next part of the puzzle, attempting to determine which processes are signalled following fiber-derived SCFA communication. After several experiments, they discovered that SCFA sets off a complex series of activities— which together form an impressive chain reaction.

Researchers found that when SCFA binds to ASC, it induces ASC to in turn attach itself to another protein called NLRP. At the same time, ASC also attaches to yet another compound known as caspase-1.

When ASC, NLRP, and caspase-1 are put together, they form a large structure called an inflammasome complex. This remarkable complex has the known ability to create multitudes of interleukins, which are compounds that stimulate the immune system’s response. These interleukins go on to perform a variety of protective functions, such as recruiting germ-killing cells to the site of infection.

Fiber for the win!

These new discoveries on fiber’s role in the immune system are a valuable insight for the field of immunology and overall health. In the future, this research could open up new ways to create potential SCFA-related treatments for infection.

As for now, it’s always a good idea to maintain a healthy fiber intake— an average of 25-30 grams a day is recommended. When I cook, I like finding quick and easy ways to add it in, such as using frozen vegetables and canned legumes in dishes. Blending veg in soups and sauces, or adding seeds to homemade baked goods, are other great ways to increase fiber consumption.

Whatever you do, every little boost helps— and your metabolism and immune system will thank you for it.

This study was published in the journal PLOS Biology.

Reference

Tsugawa H, Kabe Y, Kanai A, Sugiura Y, Hida S, Taniguchi S, et al. (2020). Short-chain fatty acids bind to apoptosis-associated speck-like protein to activate inflammasome complex to prevent Salmonella infection. PLoS Biol 18(9): e3000813. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000813

About the Author

Angie Lo is an undergraduate student at the University of Toronto, currently majoring in Physiology and English. When not writing or studying, she can be found drawing cartoons, reading poetry, or cracking her tenth corny science pun of the day.

The information contained in this article is for informational purposes only and is not intended as health or medical advice. Always consult a physician or other qualified health provider regarding any questions you may have about a medical condition or health objectives.