Children learn language for the first time in a cool way, and the good news is that adults can, too. Find out how.

By Angie Lo

For a parent, few things spark as much joy as when their child utters their first words and sentences. And it really is a wondrous moment, for learning to understand spoken language is no small feat for the brain.

When we learn a second language, we have the option of learning words by matching them to translations in our first language, and figuring out sentence structure by learning its patterns of grammar and syntax. However, children don’t have that option—they basically have to figure out a language from scratch using environmental cues, relying on their rich surroundings for a wealth of information. To help this along, an adult might describe a scene to the child while it plays out in real time, saying things like “Look at your big sister chase the dog!” or “Wow—the cat is drinking his water so fast!” This sets up an ambiguous puzzle for the child to figure out: is “cat” the furry thing? The clear liquid? The action being done? What about the other words—what do they mean? And to add on to this challenge, other things might be happening simultaneously while the scene occurs—further diminishing the preciseness of the surrounding information.

To figure out how young minds can master such a complex task, researchers at the University of Lancaster examined the cognitive processes behind it. Through their study, they uncovered much about how children learn spoken language—and the results really are something to talk about.

A study with a twist

Despite its aim being to analyze language acquisition in children, the study was performed on a group of adult participants. Although that might sound surprising, the study had a twist—they were put in the same learning situation as a young child would be. It turns out that when given the same conditions, adults have the ability to learn a new language the same way children do.

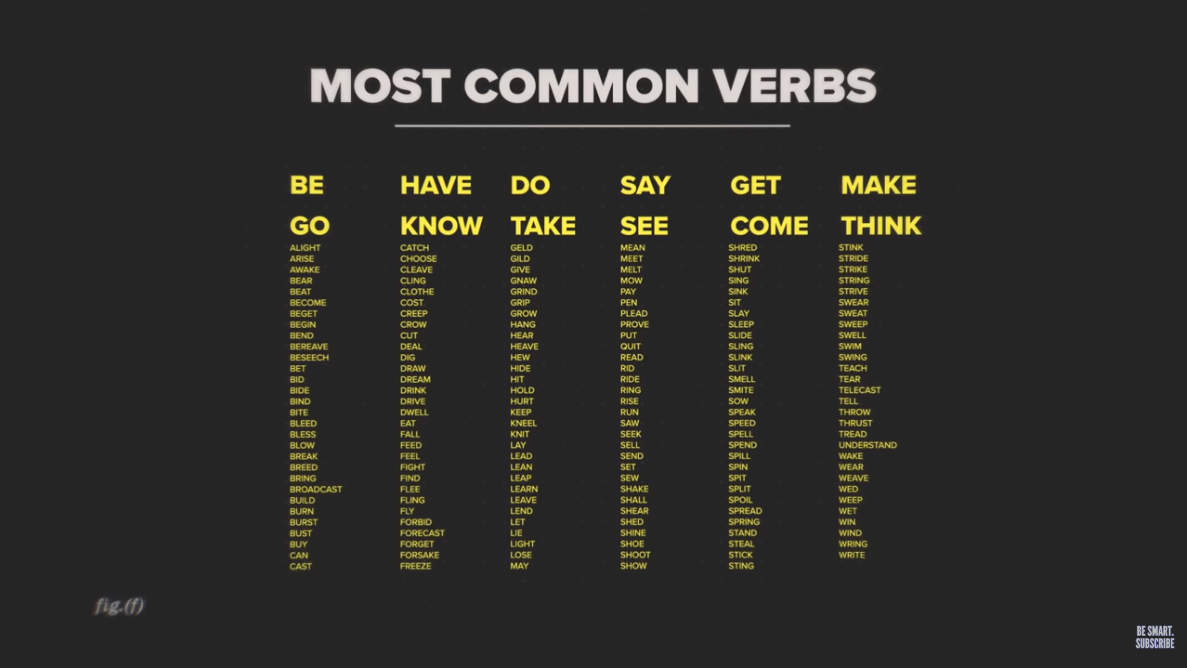

This was achieved by the researchers creating a brand-new, imaginary language, with unfamiliar words and syntax. They then used it to form a variety of fairly complex sentences, comprising multiple parts of speech such as nouns, verbs, adjectives, and prepositions.

Without receiving any information about the new language, participants were allowed to listen to recordings of the sentences while watching animations of corresponding scenes on a screen. To increase the ambiguity factor, some participants had to watch two animated scenes at once, but only one of them coincided with the utterance being spoken. To assess their learning of the language, participants were then tested on both its vocabulary and syntax.

RELATED: LANGUAGE DETECTIVES OF THE AMERICAS

The study relied on the fact that adults and children learn language similarly when placed in such a situation. By observing how older participants could acquire sentences from scratch, researchers were able to gain insight on how children do the same.

Children learn language, make links

By the end of the study, participants were able to pick up on both the language’s meanings and structures—doing so in a relatively short amount of time. Through their observations, researchers found that this outcome could be attributed to a method called cross-statistical situational learning, or CSSL.

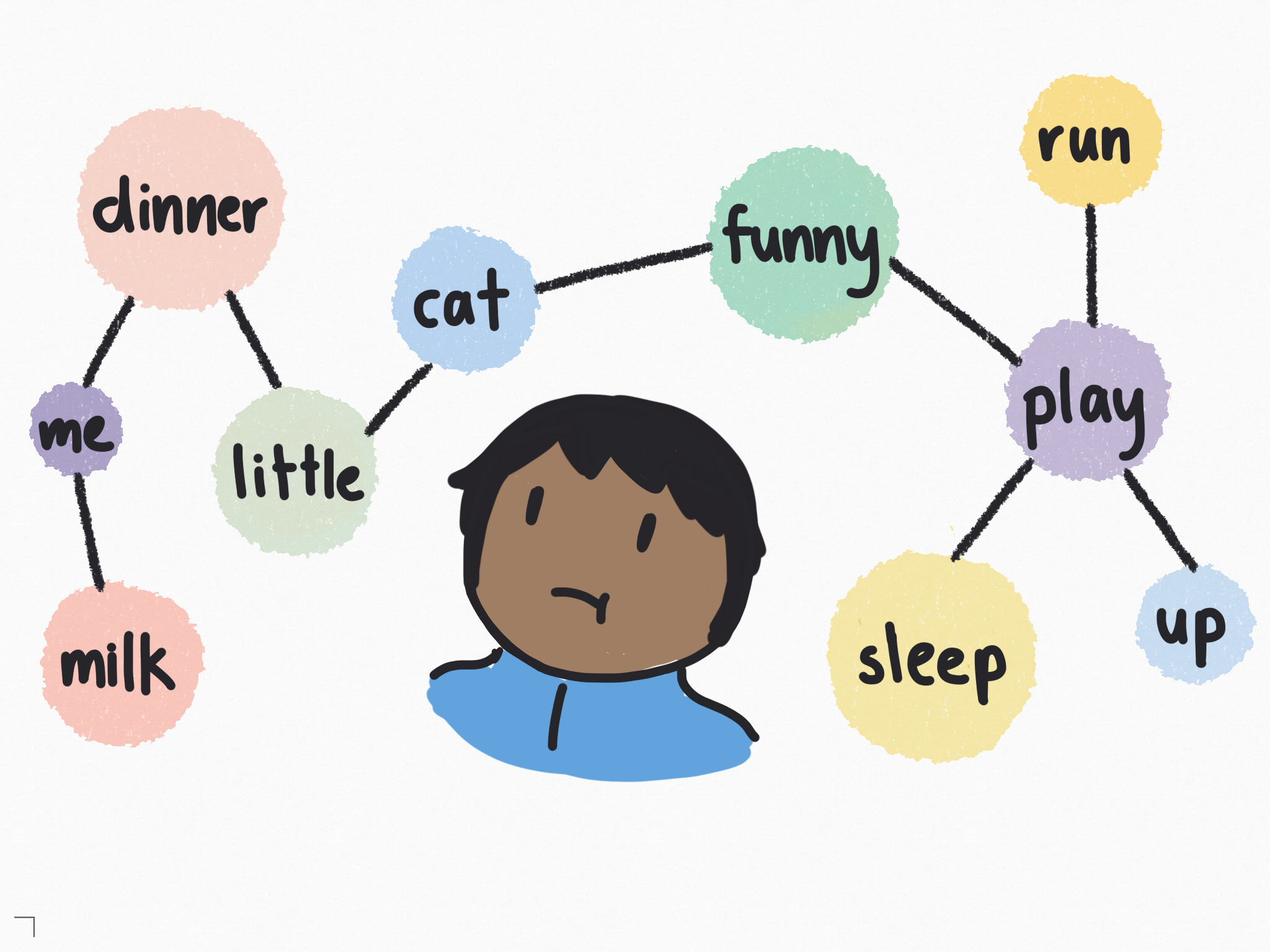

CSSL is based on the idea that our minds adapt extremely well to regularities, or events that occur often. The theory behind the method states that if two things occur simultaneously in many instances, the brain will deduce that they are likely linked, and will learn to associate them together. So when a child hears their parent say the word “cat” many times when the furry thing is nearby, the child is able to figure out what “cat” means from those repeated instances.

Two possible mechanisms for the method have been proposed. The first is the hypothesis testing mechanism, in which the child first makes a guess about what a new word might mean. As an example, if they heard their parent say, “Wow—the cat is drinking his water so fast!” they might guess that “cat” means the clear liquid. When the word is said again in another context (e.g., when water is not present), the child will change their guess to align with the differing information. This occurs until the child’s surroundings consistently match up with the word, upon which the brain confirms its meaning.

RELATED: Why Don’t We Have Memories of Early Childhood?

Another possible explanation for CSSL is the associative learning mechanism. When a word is heard, the child does not make any first guesses. Instead, their mind keeps track of all the possible meanings the word may have—it will associate “cat” with the furry thing, and the clear liquid, and the action being done, etc. All these associations are then stored in the brain like information on a computer, and build up as the word is repeated and more pairings are made. Over time, the association made most often will become stronger, “overpowering” the others in the mind and becoming the learned definition. Although it is yet to be confirmed which mechanism drives CSSL, the topic is of great interest—and future study in it would prove extremely valuable to language learners of all ages.

RELATED: HOW SOME WORDS GET FORGETTED

A word worth spreading

It has previously been shown that CSSL is used to learn new nouns and verbs in relatively clear situations. Despite this, it was thought that the method may not be powerful enough for more complex or ambiguous language elements, or environments with increased uncertainty .

However, this study proved the contrary—it was able to attribute both complex parts of speech and grammatical structure to CSSL, as well as display its effectiveness with multiple scenes occurring at once. In this way, the study demonstrates how a single method can be harnessed to master a variety of sophisticated language elements—even when situations become increasingly imprecise. Not only does it unlock new insight on learning and developmental processes in children, it also gives us a newfound appreciation for just how powerful the human mind can be.

RELATED: PREFERENCE FOR POSITIVE, HAPPY WORDS

So the next time you pass by a child gurgling out words in their stroller, take some time to appreciate the cognitive workings that led to it. The parents of the world are right—it truly is a milestone to marvel at.

This study was published in the journal Cognition.

References

Rebuschat, P., Monaghan, P., & Schoetensack, C. (2020). Learning vocabulary and grammar from cross-situational statistics. Cognition, 206. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2020.104475

Zhang, Y., Chen, C., & Yu, C. (2019). Mechanisms of Cross-situational Learning: Behavioral and Computational Evidence. In J. B. Benson (Ed.), Advances in child development and behavior (Vol. 56, pp. 37-63). London: Elsevier/Academic Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.acdb.2019.01.001

Illustrations by Angie Lo.

About the Author

Angie Lo is an undergraduate student at the University of Toronto, currently majoring in Physiology and English. When not writing or studying, she can be found drawing cartoons, reading poetry, or cracking her tenth corny science pun of the day.