Eye-movement desensitization and reprocessing, or EMDR therapy helps people with PTSD by changing the way their brains remember traumatic events.

By Pernille Bülow

Traumatic experiences can leave long-lasting impacts on the human mind and body. Some traumatized people develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which is characterized in part by intrusive fear memories, nightmares, and severe anxiety. These symptoms can be so severe that they leave people unable to work or take care of their families. Sadly, PTSD can be very difficult to treat, and it has been a major challenge to find effective treatment methods for people suffering from PTSD and other trauma-induced mental health challenges.

In research laboratories, scientists have identified neuronal pathways that underlie fear memories in mice. Researchers can form and reactivate fear memories in mice that have never experienced trauma, and they can also remove those fear memories with drugs. Unfortunately, these drugs can often not be used in humans, and clinicians such as therapists and psychiatrists instead rely on antidepressants, exposure therapy, and other psychotherapeutic techniques to treat PTSD. However, the biological mechanisms underlying these therapeutic approaches are largely unknown. This can sometimes affect how consistently the techniques are put into use.

One psychotherapeutic approach is called eye-movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy. Over the last 30 years, randomized clinical research studies have reported significant benefits to EMDR treatment for traumatized people, including those suffering from PTSD. What’s different about EMDR compared to other psychotherapies is that it involves much less talking. Instead, EMDR treatment involves a guided movement of your eyes from side to side while you recall a traumatic memory.

Francine Shapiro, the originator of EMDR therapy, found a relationship between bilateral eye movements (that is, moving your eyes from side to side) and reprocessing traumatic memories to enable healing. “Reprocessing” means that you rethink or reconsider how a memory makes you feel, and potentially even how you remember the event. Until recently we did not know the biology behind EMDR therapy. Now researchers from Hee-sup Shin’s lab at the Pohang University of Science and Technology in South Korea have identified a pathway in the brain that may mediate the therapeutic effects of EMDR therapy.

EMDR-like therapy reduces fear in mice

Shin’s group first had to test if they could reproduce the efficacy of EMDR therapy in mice. To do this, they induced fear-memories in mice by exposing them to mild electric foot shocks. With every shock, the mice also heard a sound. After a few trials, the mice feared the sound because they associated it with an electric shock. The researchers then tested if EMDR therapy would accelerate “fear extinction” in these mice. Fear extinction means becoming less reactive to a traumatic event or stimulus. In this case, the traumatic stimulus was the sound.

RELATED: How a Special Smell Triggers a Memory

To mimic EMDR therapy, the researchers took advantage of the fact that mice (and humans) will pay attention to flickers of light. They turned small lights on and off in a way that would direct the mice’s eye movements from side to side—just like in EMDR therapy. To control for the effects of light exposure (without the eye movements), the researchers exposed another set of traumatized mice to constantly flashing lights that would not direct the mice’s eyes in any particular direction.

While the lights were turned on, the mice heard the scary sound, and the researchers could measure how fearful a mouse was during the experiment. Remarkably, the lights that directed the mice’s eyes from side to side led to a much faster fear extinction compared to any of the other groups (flashing lights or no lights). This result showed that guided eye movements accelerate fear extinction in mice. The reduced fearfulness to the previously scary sound lasted for a week after the fear extinction experiment, suggesting that the EMDR-like therapy induced long-lasting changes in the mice’s brains.

EMDR therapy and the brain

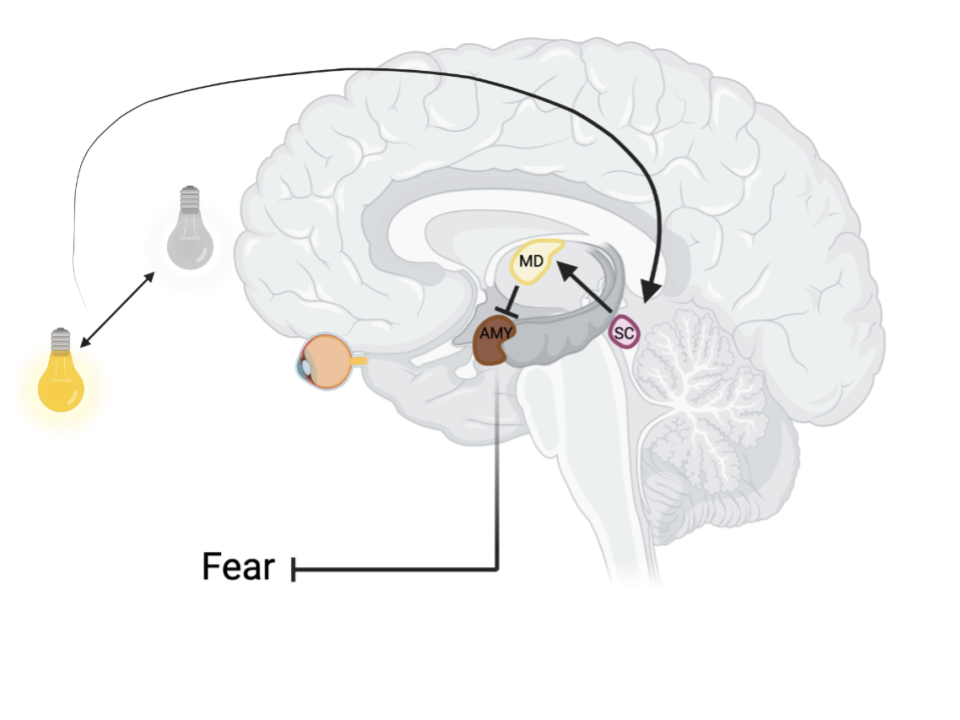

Now that the researchers had found a way to mimic EMDR therapy in mice, they could finally start investigating how this therapeutic approach affects the brain. To do this, they performed single-unit recordings in three different brain regions. Single-unit recordings involve an electrode which is delicately placed in a brain area. When the brain region is active, a voltage signal is measured by the electrode. The researchers hypothesized that a brain region called the superior colliculus would be important in mediating the therapeutic effects of EMDR therapy due to its role in directing our eye movements and attention to cues that stand out in our environment. Indeed, they measured more activity in the superior colliculus with the bilaterally activated lights compared to flashing or no lights.

The superior colliculus is also connected to a number of other brain regions that are important for emotional processing. One of these regions is called the mediodorsal thalamus, and it plays an important role in fear memories because it forms tight connections with the amygdala and prefrontal cortex, two regions in the brain that are critical for regulating emotional responses and memories. Just like with the superior colliculus, bilaterally activated lights led to heightened activity in the mediodorsal thalamus. In fact, if they used chemical tools to block the connection between the superior colliculus and mediodorsal thalamus during the guided light activity, the mice no longer experienced accelerated fear extinction.

When the scientists moved the single-unit electrode to the amygdala, they found that the EMDR-like therapy led to reduced neuronal activity. That makes sense because the amygdala is usually active when you are scared. Their data supported the idea that EMDR therapy reduced fearfulness because it reduced amygdala activity. Why was the amygdala’s activity reduced when the other regions saw increases? In short, each brain region is made up of a lot of different types of neurons, and these can be broadly classified into “excitatory neurons” and “inhibitory neurons.” Excitatory neurons from one brain area activate neurons in another, while inhibitory neurons silence other neurons. When the EMDR-like therapy activated excitatory neurons from the superior colliculus to the mediodorsal thalamus, this led to increased activation of inhibitory neurons in the mediodorsal thalamus that connected to and silenced neurons in the amygdala.

Notably, one week after the mice who underwent EMDR-like therapy experienced fear extinction, that inhibitory connection was still enhanced. This persistent change in neuronal activity may explain the long-lasting effects of EMDR therapy.

Looking forward

Shin’s group found that EMDR-like therapy in mice sets off a chain reaction in the brain that results in reduced fearful reactions to a previously scary sound. In other words, EMDR-like therapy in mice leads to a reprocessing of the memory from being fear-triggering to non-fear-triggering. EMDR therapy in humans may be particularly effective for people with PTSD because it helps them reduce the emotional intensity of their traumatic memories. Hopefully more people will benefit from EMDR therapy as we increase our understanding of the biological mechanisms underlying its effectiveness. This research was published in the peer-reviewed journal Nature.

References

Baek, J., Lee, S., Cho, T., Kim, S.-W., Kim, M., Yoon, Y., Kim, K. K., Byun, J., Kim, S. J., Jeong, J., & Shin, H.-S. (2019). Neural circuits underlying a psychotherapeutic regimen for fear disorders. Nature, 566, 339–343. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-0931-y

De Jongh, A., Amann, B. L., Hofmann, A., Farrell, D., Lee, C.W. (2019) The status of EMDR therapy in the treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder 30 years after its introduction. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 13(4). https://doi.org/10.1891/1933-3196.13.4.261

About the Author

Pernille Bülow has a PhD in Neuroscience and currently works as a Product Specialist on neurophysiology at iMotions. She is passionate about understanding and questioning the mind-body relationship. In her spare time, Pernille practices fencing, horse riding, performing aerial acrobatics and reads lots of fiction. Find her on LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/pernille-bülow or Instagram: pernillebuelow.