How Our Brains Learn to Use Tools

Scientists in Munich have examined how human brains learn to use tools, and the findings might help stroke victims.

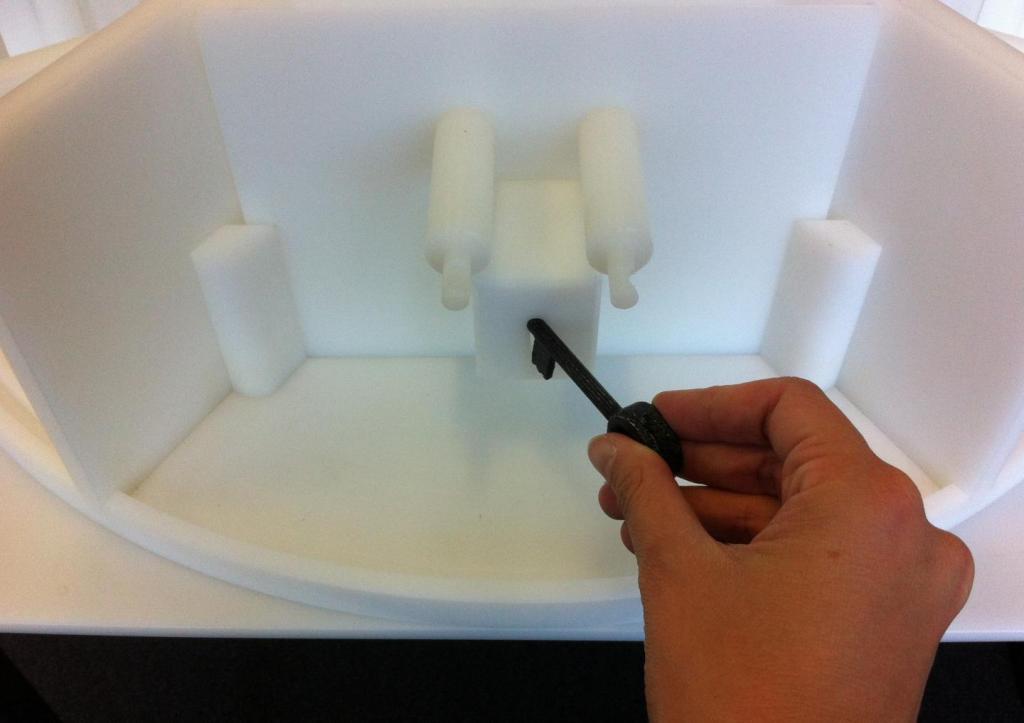

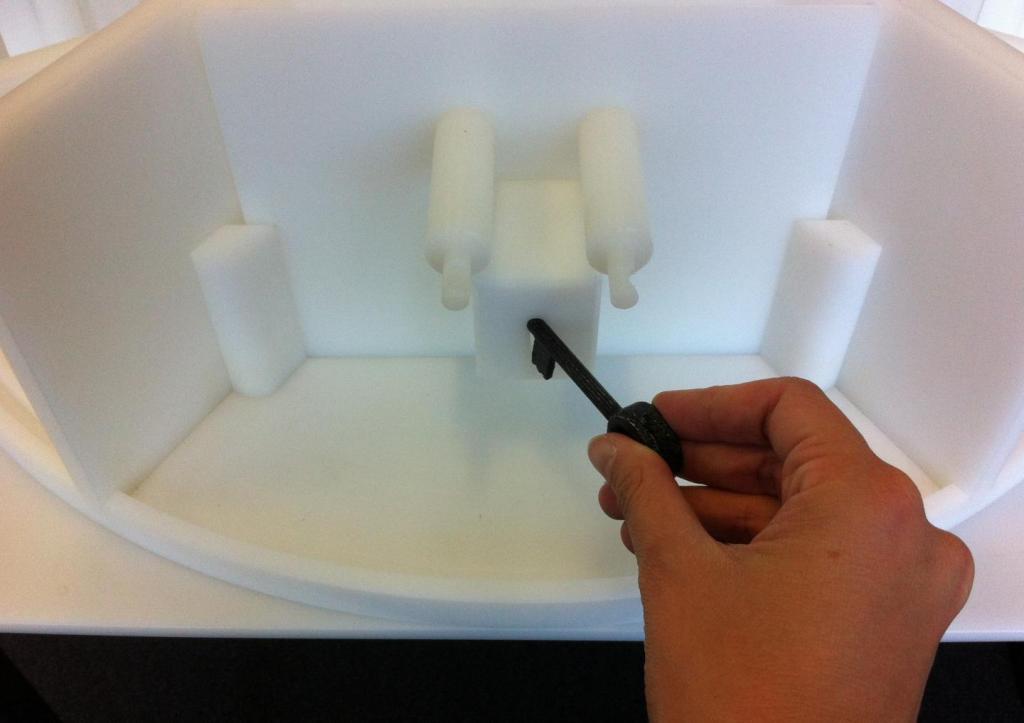

How do our brains learn to use everyday tools and utensils, such as car keys or chopsticks? That’s exactly what researchers from Technische Universität München (TUM) and the Klinikum rechts der Isar hospital have been analyzing networks in the brain to figure out. Using MRI scans, they watched the areas of the brain that activate when a person first thinks about using a tool and then actually picks it up and uses it.

After giving people some everyday items to use, including a hammer, a bottle-opener, a key, a lighter, scissors, and some unfamiliar objects, researchers used MRI scans to watch their brains in action.

What the researchers saw was that the left hemisphere was activated when the subjects planned to use a tool. The researchers also saw a distributed network responsible for both planning and execution. When the test subjects handled unfamiliar objects, these regions of the brain were less active. Essentially, our brains light up more when we use tools that we’ve handled before.

How Our Brains Learn to Use Tools

The study revealed what the researchers are calling a “tool network.” It activates when we recognize an object as a tool (or a potential tool), think about how to use it, then pick it up and put it into action. For example, how many times have you turned on a computer? Too many to count? If you want to turn on your laptop computer, your brain formulates an action plan. It knows that you need to open the lid and press the power button. You probably don’t think very hard about that process, but your brain works through each step, and that is how our brains learn to use tools.

“The study also allowed us to confirm that there are different streams of perception in the brain for different tasks,” explains Joachim Hermsdörfer from TUM’s Chair of Human Movement Science. The dorsal stream of perception sends signals to the posterior parietal lobe and is generally responsible for controlling actions. “It can be divided into two function-specific processing pathways. Thedorso-dorsal stream controls basic gripping and movement processes, regardless of whether the person is familiar with the object or not. A second ventro-dorsal stream becomes active when we use tools that are familiar to us.

RELATED: BETTER UNDERSTANDING THE HUMAN GRIP

This work may help to improve medical practices for people who struggle with the motor skills necessary for tool use. For example, people who can’t button up their jacket or who find it difficult to insert a key in lock suffer from a condition known as apraxia. This means that their motor skills have been impaired. That impairment reduces the ability to use tools. Sometimes the apraxia is a result of having a stroke. Armed with more detailed knowledge of how the brain plans and executes tool use, doctors may be able to provide better diagnoses of apraxia and improve therapeutic techniques in the future.

Music Also Helps Stroke Victims Recover

Research suggests that music and lyrics are helping stroke victims recovery language skills. Researchers at the University of Helsinki have found that listening to music with lyrics could help rehabilitate stroke survivors and restore their language skills.

RELATED: BIOLOGIST EXPLAINS HOW WE LEARN TO CATCH

These research findings have been published in the Journal of Neuroscience.

References

Brandi, M., Wohlschlager, A., Sorg, C., & Hermsdorfer, J. (2014). The Neural Correlates of Planning and Executing Actual Tool Use. Journal of Neuroscience, 34(39), 13183-13194. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.0597-14.2014

Orban, G. A., & Caruana, F. (2014). The neural basis of human tool use. Frontiers in Psychology, 5. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00310

RELATED: Neuromodulation: How We Manipulate Brain Cells