What are sunsets? To human eyes, they are very cool optical illusions. Learn about light scattering, visual perception, and how to photograph sunsets.

“It is sometimes said that scientists are unromantic, that their passion to figure out robs the world of beauty and mystery. But is it not stirring to understand how the world actually works — that white light is made of colors, that color is the way we perceive the wavelengths of light,[…] and that the sky is blue for the same reason that the sunset is red? It does no harm to the romance of the sunset to know a little bit about it.” (Carl Sagan, Pale Blue Dot)

Time is an Illusion, Sunsets Doubly So

Admittedly, it is a beautiful optical illusion. When we think we are seeing the Sun setting, it may already be below below the horizon, because atmospheric refraction allows us to see the Sun around the curvature of the Earth. Several other aspects of sunsets are optical effects or illusions.

![Sunsets: Four minutes later the sun is sinking behind a cloud and the quality of the light is different. The cloud edges look fractalicious. [EOS 7DmkII: 400mm, f6.3, ISO 100, 1/800 sec]](https://magazine.scienceconnected.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/3A4A2843-crop-2058-1146-e1443210886191.jpg)

The Sun’s apparent size and shape are also optical illusions. There are two factors at work which apply to the Sun, the Moon, and the stars. One is a perceptive factor. The other is explained by refraction.

The Moon Illusion

Earth’s moon (or its sun) appears larger on the horizon than when it is higher in the sky. Although its angular dimensions remain constant, humans perceive the Moon to be larger when it is near the horizon. There are several theories about this. Two of them can be quickly appreciated visually.

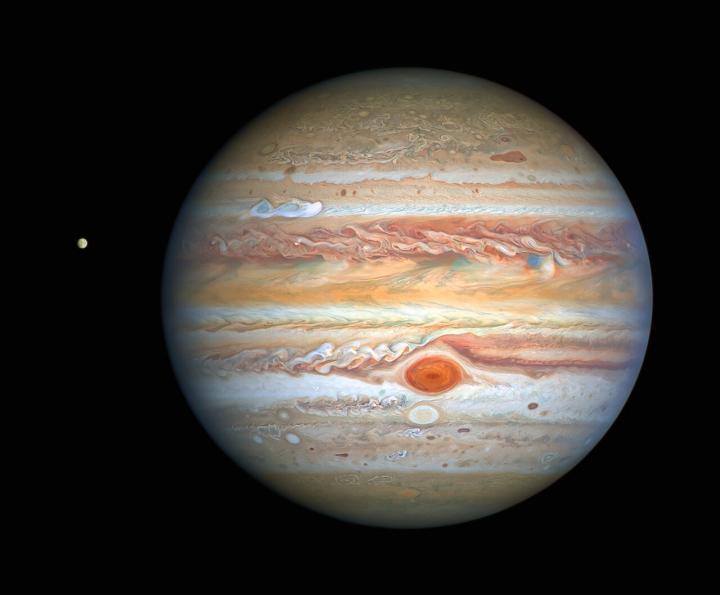

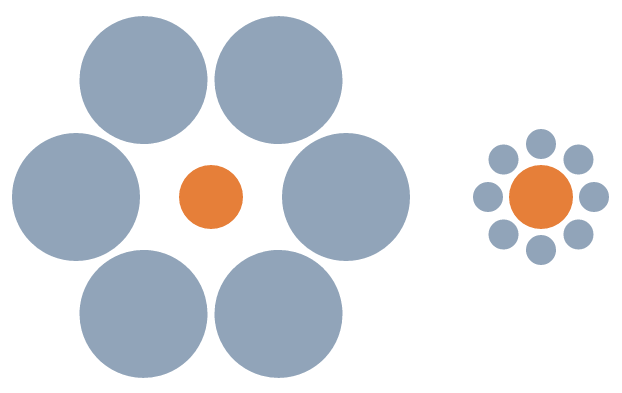

The Ebbinghaus Illusion is one of the favored ways of explaining why we perceive the Sun or Moon to be larger near the horizon. If the Moon is high above the horizon there are large expanses of space or clouds around it. When the Moon is near the horizon there may be objects near it which appear small. These objects could be distant clouds, buildings, hills or even trees. Distant objects in the field of vision near the Moon make us perceive the Moon as large relative to these objects.

Another potential explanation is the Apparent Distance Hypothesis, which is easily illustrated by the Ponzo Illusion. This says that the perceived size of an object is related to its background. If the object is near the distant horizon, we are conditioned to think of it as larger than the same size object overhead.

Bending Light

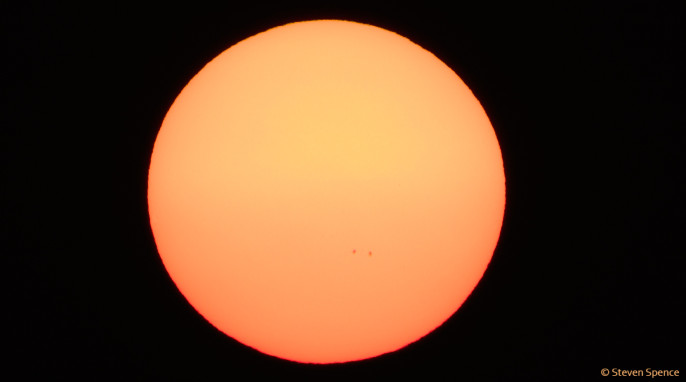

Due to the low angle of the Sun relative to the observer at sunset (or sunrise), light passes through more of Earth’s atmosphere than when it is overhead. The Sun’s light is subject to both refractive and scattering effects. Refraction can make the bottom part of the Sun, which is near or even below the horizon, appear higher than it actually is. This can give the Sun a distorted appearance that resembles an oval more than a sphere.

Near the horizon, scattering of shorter wavelengths of light occurs as it passes through the atmosphere. This is why the blue and green components of light from the Sun drop off significantly for an observer at sunrise or sunset. Yellow, orange, and red wavelengths are longer and less affected by atmospheric molecules, which is whymore light in those wavelengths reaches us, making us perceive sunsets as having golden or reddish colors.

![Overexposed for the sun (blown out), but good to capture the golden sky. Newport Beach, CA. U.S.A. [EOS 60D: 300mm, f7.1, ISO 125, 1/400 sec]](https://magazine.scienceconnected.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/IMG_9630-cc-down-2058-1156-e1443211468746.jpg)

Sunsets and Additional Atmospheric Effects

Particles in the atmosphere from clouds, fires, or volcanic eruptions can also affect how sunlight is transmitted. Sunsets may be especially vivid when volcanoes eject dust particles or droplets of sulfuric acid into the upper atmosphere.

Another atmospheric effect that may result in more refraction and distortion than usual is a temperature inversion. Inversions often result in a Fata Morgana (a specific type of superior mirage) making a distant object appear higher above the horizon than it actually is.

![Sunsets: The sun is very low on the apparent horizon and shows distortion due to refraction (vertical compression) and atmospheric effects (ragged edges). the black arrow indicates a green fringe at the upper limb of the sun. Newport Beach, CA. [EOS 60D: 400mm, f8, ISO 250, 1/640 sec]](https://magazine.scienceconnected.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/IMG_9653-cc-cropped-1372-764-e1443211587272.jpg)

Green Light

When conditions are right it is possible to observe a flash of green light at the end of the sunset. This is due to refraction. Usually a green fringe can be observed at the top edge of the Sun; however, a green flash is rarer to observe. The green flash appears just above the rim of the Sun for one or two seconds.

Keep Your Eyes Safe!

While sunsets are lovely, do be careful observing them. It is dangerous to stare directly at the Sun, even during sunrise or sunset. When using equipment that magnifies the sun, such as binoculars, a telescope, or even a telephoto lens, the time it takes to damage your eyes is much shorter. For this reason, a proper filter is essential to protect your eyesight and possibly also prevent damage to your equipment.

Snapping Sunsets: Pro Tips for Photographers

In my experience, the camera’s exposure meter does a great job for most conditions, but frequently is quite poor at capturing the sun or moon. I will usually get overexposed images in which the Sun or Moon appear featureless (blown out). I generally switch to a manual exposure mode and shoot a few pictures at different settings until I get shots that let me see features. Because conditions will vary due to temperature and weather (no clouds, a thin layer of clouds or particles in the sky), some adjustments will be necessary even when I use the same equipment.

For photos of the Sun using my current camera (EOS 7D Mk II), I start by setting the ISO to the lowest possible value on my camera (ISO 100) and focus somewhere on the horizon. I then lock the focus by switching it to manual focus. I also set a very short exposure time. Another setting you can use to make adjustments is the aperture (f-stop) setting. A good initial setting for me may be f8 and 1/640 second. Often I need to vary the aperture/exposure time over three or four shots before I find the right settings. Once again please always be sure to protect your eyes when observing the Sun!

Knowing how a sunset works doesn’t make it any less beautiful or magical, so get out there and watch our star set (or rise) when you get the chance.

For Further Reading

Why the moon looks so big on the horizon (Discover)

Example of sunset due to volcanic eruptions

Safe Solar Viewing Tips (National Geographic)

Featured image: Sunset seen at the coast in Novigrad, Croatia. Thin clouds turn a normal sunset into a sci-fi worthy sunset. [EOS 7DmkII: 400mm, f5.6, ISO 100, 1/2000 sec]. Photographed by Steven Spence

This article was originally published in 2015.

![Sunsets: Sunset seen at the coast in Novigrad, Croatia. Thin clouds turn a normal sunset into a sci-fi worthy sunset. [EOS 7DmkII: 400mm, f5.6, ISO 100, 1/2000 sec]](https://magazine.scienceconnected.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/3A4A2828-down-cropped-2058-1146-e1443210710946.jpg)