Models suggest HPV tricks the immune system by producing a decoy viral protein to distract from its infectious viral proteins.

Not many pathogens are smart enough to overcome our body’s innate and adaptive immune systems. However, in a study published in eLife, researchers at the German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ) have discovered how cutaneous human papillomaviruses (HPV) may be outsmarting the adaptive immune system, the one that produces antibodies.

Previous studies have shown that the human immune system produces antibodies against the short L1 and L2 proteins on the surface of the virus and effectively neutralizes it. However, since HPV is known to cause long-term infections, Fu et al. decided to look into the modus operandi of the virus more closely.

The viral proteins were actually produced about four months after the onset of infection. Have you ever clicked on a celebrity gossip article and later realized that the website stole your credit card information? Exactly.

What they found was that the virus is just a little smarter than previously estimated. It produces what can be analogized to clickbait—a longer version of the L1 protein, an ineffective one that grabs the attention of the body’s immune system and causes it to produce antibodies specific to it. While the body works to neutralize the longer, non-infectious L1, the shorter and infectious L1 latches on to the body’s cells, replicates, replicates some more, and infects them.

The team also found that the antibodies specific to the functional L1 viral proteins were actually produced about four months after the onset of infection. Have you ever clicked on a celebrity gossip article and later realized that the website stole your credit card information? Exactly.

Immune system trickery

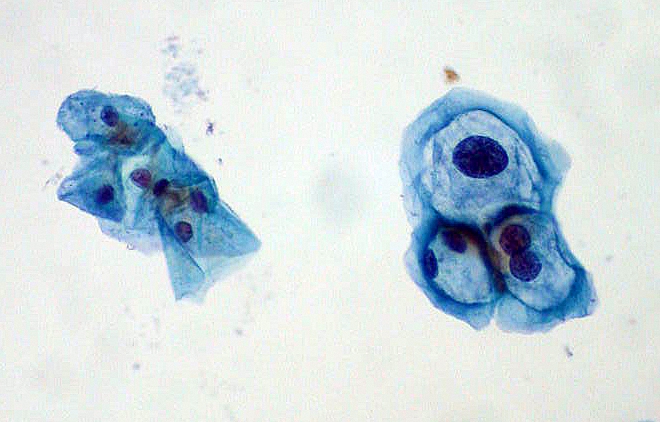

Cutaneous HPVs are common viruses that affect the skin. Combined with external factors such as exposure to UV radiation and the strength of the body’s immune system, they may have long-term effects and cause diseases including skin cancer in humans.

Under usual circumstances, the human body has multiple walls of defense set up to overcome infection by a virus. The virus must deal with the innate immune system before it can move on to the adaptive immune system, and only if it breaches the adaptive immune system can it cause an infection. While there are many pathogens that can outwit the innate immune system, they are almost always destroyed before they can infect the body’s cells by the adaptive immune system via antibodies.

In the case of HPV, the adaptive immune system produces antibodies specific to the L1 and L2 proteins on the surface of the virus and effectively neutralizes the threat of infection. The L1 and L2 proteins form the viral particles that cause infection, which is called the capsid of the virus.

Viruses can have long-term effects

Sometimes, however, cutaneous HPV can have long-term effects, and the reason for this was unknown. Scientists didn’t know how the virus was able to overcome the body’s defenses and have a long-term impact when the adaptive immune response was in place, producing antibodies specific to the viral capsid.

In this study, Fu et al. used mouse models (Mastomys coucha) to demonstrate exactly how this happens. The immune systems of these mice are compromised by a strain of cutaneous papillomavirus called MnPV shortly after birth, and they produce antibodies specific to L1 and L2 viral proteins much like humans do, so they could be used to see how HPV works. These mice are also used as a model to study how cutaneous HPVs cause skin cancer.

Upon infection with MnPV, the mice were assumed to produce antibodies against the L1 and L2 proteins, preventing the virus from entering the host cell and replicating to cause an infection. In the study, however, researchers found that the virus also produced a longer, non-infectious version of the L1 protein. Once the mouse’s immune system was busy trying to neutralize the threat of the longer L1 protein, the shorter L1 and L2 proteins entered the host cell undeterred, causing an infection.

This, according to the researchers, is how cutaneous HPVs can outsmart the body’s adaptive immune system and have a long-term impact without being neutralized by antibodies. The antibodies specific to the functional viral protein L1 are produced long after the body’s cells are infected. This begs the question, can this information be used to prevent the onset of skin carcinomas caused by cutaneous HPVs? And if HPV can outsmart our body’s immune system, who’s to say that other viruses don’t behave the same way?

References

Hagensee, M. E., Yaegashi, N., & Galloway, D. A. (1993). Self-assembly of human papillomavirus type 1 capsids by expression of the L1 protein alone or by coexpression of the L1 and L2 capsid proteins. Journal of Virology, 67(1), 315-322. doi:10.1128/jvi.67.1.315-322.1993

Hasche, D., & Rösl, F. (2019). Mastomys species as model systems for infectious diseases. Viruses, 11(2), 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/v11020182

Hasche, D., Vinzón, S. E., & Rösl, F. (2018). Cutaneous papillomaviruses and non-melanoma skin cancer: Causal agents or innocent bystanders? Frontiers in Microbiology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.00874

About the Author

Risha Banerjee is an undergraduate student at UBC Vancouver, majoring in biochemistry. She owns two ukuleles and a guitar and can often be found staring at walls, journal in hand. An avid procrastinator, she could probably be the president of the “I’ll do it tomorrow” club. Find her on Instagram @risha_banerjee.

The information contained in this article is for informational purposes only and is not intended as health or medical advice. Always consult a physician or other qualified health provider regarding any questions you may have about a medical condition or health objectives.