Want to learn more about this initiative? Check out the Wicked Hot Boston series, Parts One and Two. Want to address climate hazards in your community? Head over to SciStarter.org/NOAA to find a citizen science project.

Wicked Hot Boston

It’s true: the world is getting hotter, and Boston is becoming WICKED hot.

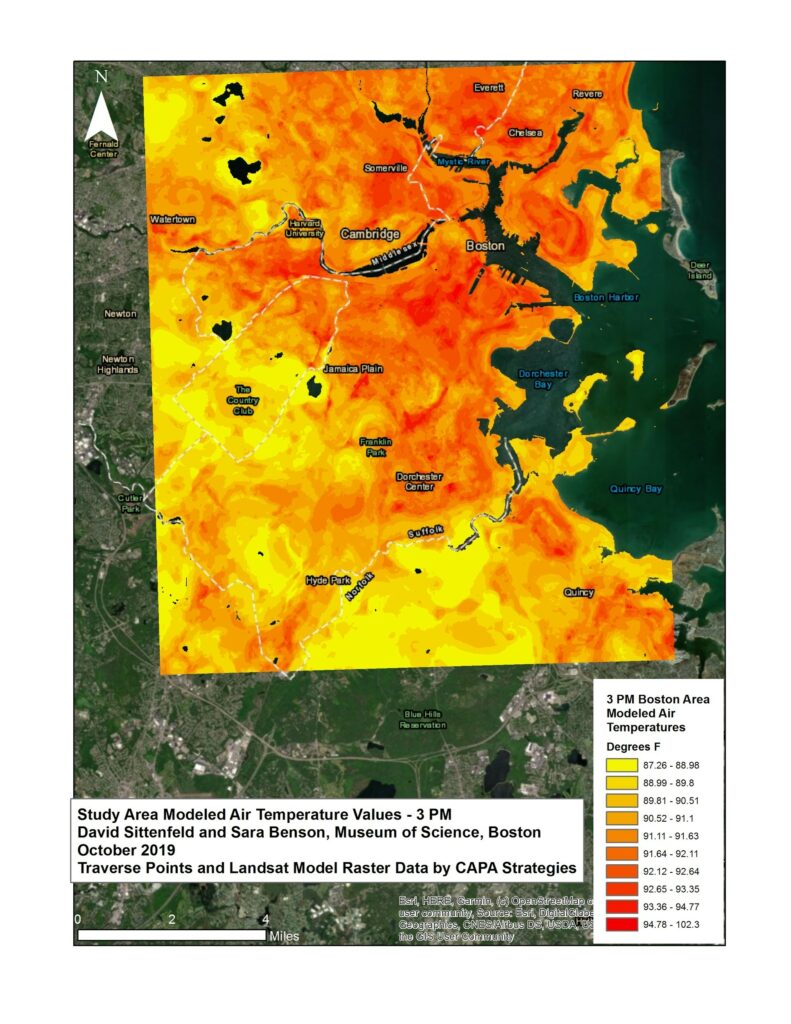

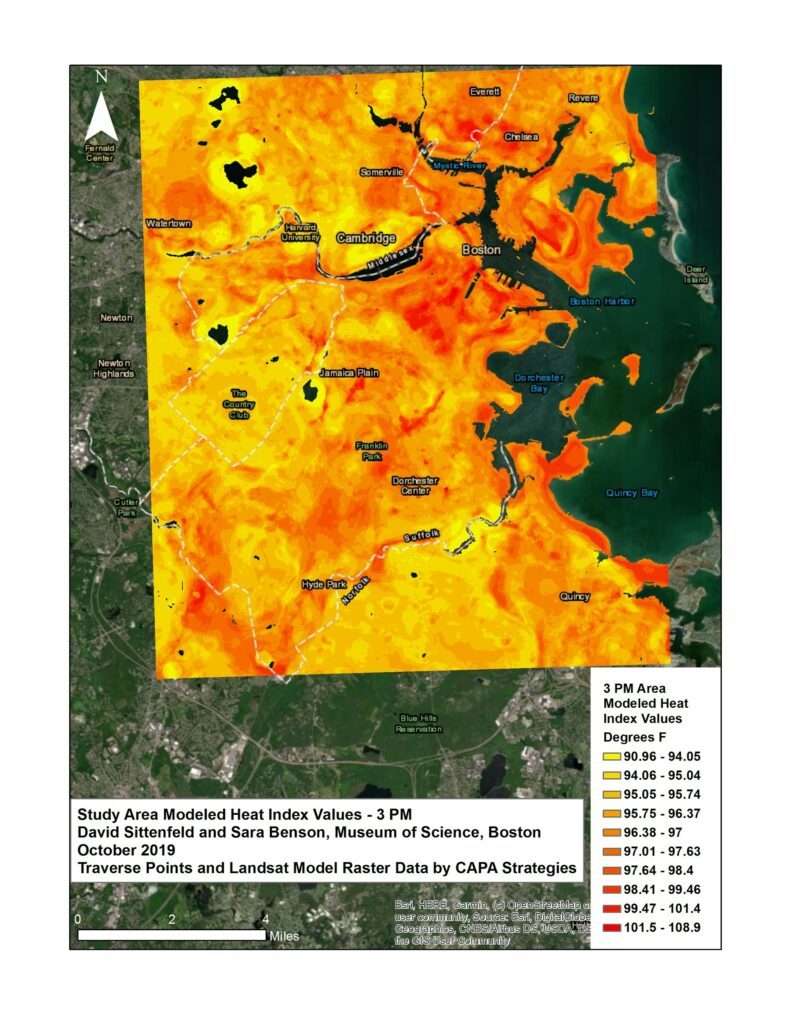

This past summer, the Museum of Science, Boston (MOS) team and local citizen scientists began to measure extreme temperatures. They used sensors provided by CAPA Strategies to make an ambient air temperature map of Boston, Cambridge, and Brookline, MA.

The MOS team and area citizen scientists also contributed their qualitative and quantitative data about heat in Boston through ISeeChange, a citizen science platform that leverages community members as the experts in their own backyards to study how the climate and weather are changing around them. For the Wicked Hot Boston project, ISeeChange created an extreme heat investigation with MOS. Citizen scientists contributed over 100 observations to this investigation after reading instructions on SciStarter.org/NOAA.

The Boston Climate Hazard Resilience Forum

After activating these citizen science efforts over the summer, the MOS team hosted a community forum on climate hazard resilience, called Wicked Hot Boston, on the evening on Tuesday, September 24 2019, specifically focusing on extreme heat.

MOS forum programs “engage participants in deliberative, inclusive conversations about issues that lie at the intersection of science and society,” gathering “museum visitors, scientists, and policymakers to share their perspectives and learn from one another.” The forums can span the realms of human health, outer space, climate hazards – and beyond.

The Climate Hazard Resilience Forum templates address four environmental hazards: extreme heat, extreme precipitation, sea level rise, and drought. The forum deliberations create a simulated resilience planning experience, guiding public participants through discussions that involve making tough decisions to protect the city, and encouraging open dialogue with local resilience planners.

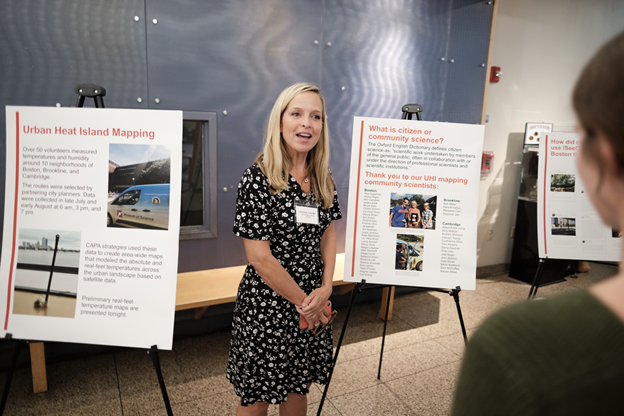

For this extreme heat forum, funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the MOS team drew preliminary conclusions from the citizen science data, which were presented in a poster session to the members of the public as they walked into the Museum of Science. Soon after, the participants went upstairs to engage in the extreme heat deliberation. Participants included people who had collected the citizen science data with MOS and people who wanted to learn about and discuss extreme heat.

Chris Mastroianni, a veteran of multiple MOS forums, talked to the SciStarter team about what keeps him coming back. “It’s the opportunity to learn more things, and then the ability to have a more engaged way of speaking about the issues.”

In terms of what he learned at the Wicked Hot Boston forum, Mastroianni said before the forum, he wasn’t as aware of the “different concerns various stakeholders have.”

Participants made decisions about mitigating the effects of extreme heat for an anonymized city. Trained facilitators directed small groups at different tables to allocate limited resources among three different resilience plans: cool the city, protect infrastructure, and ensure safety. The plans were made by taking into account varying community priorities, manifested in profiles of different stakeholders such as local business owners and residents.

To balance the concerns of different stakeholders, Mastroianni’s table decided to equally allocate their money to each of the given resilience plan options. Then, through ESRI Storymap visualizations, they visualized the results of their plan. Because they made small interventions in a number of areas, their impact was dispersed – for better or worse.

Stephanie Smallegan, assistant professor of Coastal Engineering, came in from the University of South Alabama to explore how the Gulf Coast Exploreum Science Center in Mobile, Alabama can host a similar forum focused on an environmental hazard. She stepped in as a facilitator, and she said that her table was very “practical.”

“I had a surgeon, computer engineers, and a business owner at my table. They thought about things from a realistic perspective — taxes, property values — but they gave very little weight given on the social perspective,” she said.

Smallegan said her main contribution as a facilitator was to stimulate discussion by asking prompting questions, while staying neutral about the outcome of the exercise. “I brought up hypothetical perspectives and impacts on social aspects.”

As Executive Director of OARS, an organization that works to protect and improve the Assabet, Sudbury, and Concord rivers, Alison Field-Juma is intimately familiar with environmental issues. She was excited by the citizen science maps she helped create as a volunteer.

“The map is based on real temperature readings from people driving around in their cars, so people connect with that better,” she said. “The value is added by the data being immediately sensed, not remotely sensed. It is what people would feel walking down the street.”

Field-Juma appreciated following up the experience of being a citizen scientist with the forum. She said she was able to exercise a different part of her mind calling the forum deliberation both “challenging” and “interesting.”

“With this game, you have to make a series of difficult choices,” she said. “You have to figure out what matters to each person with limited resources, working in an austerity economy. The decision-making is rigorous. For example, how can you say you don’t care about public safety?”

Hearing from Resilience Planners

After the forum deliberation on extreme heat, John Bolduc, Environmental Planner for the City of Cambridge; Nancy Smith, Program Manager for Community and Resilience Engagement for the Office of Public Health Preparedness, a division of the Boston Public Health Commission; and Kara Brewton, Economic Development Director for the Town of Brookline, spoke on a panel to answer community questions.

When asked about how the citizen science data could aid him in resiliency planning, Bolduc answered, “with satellite maps, you don’t take into account climatic factors like wind or breezes…this data reflects this and adds richness.”

Smith emphasized the public educational value of citizen science data and outreach, saying that “having this data brings it to a level that people can understand.”

After discussing a multitude of plans for a fictionalized city throughout the night, participants wanted to know what they can do in their communities when they leave the forum. Brewton advised attendees to “talk to people outside of your circle…whatever your experience, knowledge, or interest is…be willing to go to other meetings. For example, public health experts could help with an urban forestry plan.”

Addressing Environmental Hazards at Science Centers Across the Country

The day after the forum, the Museum of Science and its partners, including representatives from NOAA, Arizona State University, Northeastern, ISeeChange, and SciStarter, gathered with science centers from across the country to explore how they can host forums on different environmental hazards, linking citizen science with resilience planning through various citizen science projects. What will they pick? Will it be extreme heat, drought, extreme precipitation, or sea level rise?

Eric Havel, of the Chabot Space and Science Center in Oakland, California, said his institution was leaning toward drought, but also considering addressing sea level rise and extreme heat. He said all three of the hazards were applicable to the Bay Area.

For example, drought hits home at a hyper-local level when community members think of the redwood forests. He said patrons can “step outside and realize the impact of drought,” and drought is a “near-term concern, with air quality from wildfires being in the news.”

Havel also thought that drought would be a great avenue for working with outdoor partners and programming, as well as a good way to build on previous efforts. He was particularly excited to use technological tools, like ArcGIS, GoogleEarth, and the Chabot Center’s planetarium to tell earth science stories.

“We did drought and sea level forums from earlier this year, and we had over 50 participants, with 20% of attendees being teachers,” Havel said. “The event was well-received: we played games, hosted planners who addressed the redwood forest and the coast and did a visualization piece in our planetarium.”

Do you also want to address climate hazards with citizen science? You can start today! Head over to SciStarter.org/NOAA to learn how you can get involved.

The Climate Hazard Resilience Forum was developed in partnership with Arizona State University and Northeastern University and supported by a NOAA Environmental Literacy Grant, with materials created by the Museum of Science, Boston under the awards NA15SEC0080005 and NA18SEC0080008 from the Environmental Literacy Program of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. Department of Commerce. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations within are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views

About the Authors

Emily Hostetler

As Forum Education Associate II at the Museum of Science, Boston, Emily creates and oversees a variety of forum projects throughout the year. She premiered the pilot forums on climate intervention research in Boston and Phoenix in 2018, and was a member of the team that built the nationally-implemented NOAA funded forums on extreme weather hazards. She is currently working with multiple local institutions to develop community-based forums to discuss substance use disorder and affordable housing in the Greater-Boston Area. Before joining the museum, Emily received her BA from Ohio Wesleyan University where she studied Biology and Journalism.

Sara Benson

Sara Benson is a Forum Education Associate in the Forum Department at the Museum of Science, Boston. Sara is mainly focused on the Citizen Science, Civics, and Resilient Communities project and is passionate about resiliency strategies on climate hazards. Sara has her MA in Marine Affairs from University of Rhode Island and her BS in Marine Biology from University of North Carolina Wilmington.

Caroline Nickerson

Caroline is a Master of Public Policy student at American University with a focus on environmental and climate change policy. She also works with the UF-VA UNESCO Bioethics Unit, the Christensen Project, the DC Gator Club, and the Commission on Local Debates. Caroline manages SciStarter’s Syndicated Blog Network, which encompasses the Science Connected, Discover Magazine, and SciStarter platforms, and manages programs at SciStarter.

David Sittenfeld

David Sittenfeld is Manager of Forums and National Collaborations at the Museum of Science. David has been an educator at the Museum for 20 years and oversees special projects pertaining to issues that lie at the intersection of science and society. He is also completing his doctoral research at Northeastern University, which focuses on participatory methods and geospatial modeling techniques for environmental health assessment and public engagement.