In medieval times, the narwhal tusk was bought and sold as a “unicorn horn.” It is actually a very long tooth, but it is still very cool.

By Mark Lasbury, PhD

Zootopia opened in movie theaters on March 4, 2016. Among all the animals featured in this feature, you probably recall a few sporting horns. But did you happen to spot any unicorns?

Mythical Unicorns

The earliest writings that describe unicorns were those of the Greek writer Ctesias, in the late fifth century BCE. He described the Indian ass, an animal with a white, strong body and perhaps a red head from which sprung a long single horn of red, white, and black. Ctesias believed that a cup made from its horn could neutralize any poison.

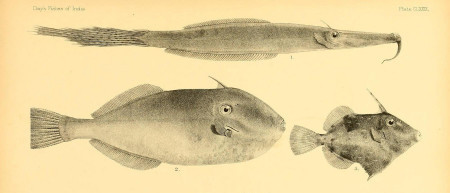

There are real animals with one horn, like the unicorn leatherjacket fish, and the Indian rhinoceros. The rhinoceros beetle has one big horn and fairly large part of his jaw below, so I do not know if he counts.

Four hundred and fifty years later, the Roman historian Pliny the Elder also wrote about very strong animals with a single horn protruding from their forehead. He described an oryx (an antelope with a single horn), an Indian ox (probably a rhinoceros, whose name comes from the Greek rhinós, nose, and kerás, horn), and the same Indian ass with a horse-like build and a single horn.

Pliny wrote that, “The unicorn (from the Latin uni, one, and cornus, horn) is the fiercest animal, and it is said that it is impossible to capture one alive. It has the body of a horse, the head of a stag, the feet of an elephant, the tail of a boar, and a single black horn three feet long in the middle of its forehead. Its cry is a deep bellow.” Uh-huh. That doesn’t sound much like an antelope or a rhino, so I guess he meant the Indian ass.

Romans traded long spiral tusks, but no one was telling where exactly they had come from. These horns were snow white with a tight spiral. As a result of these horns, the mythical unicorn in the West settled down to be a pure white horse with a very long, pure-white, spiraled horn. This is the image we generally see in tapestries and illustrations.

In the Far East there were unicorns as well. Known as the qilin (pronounced chee-lin) in China and as the kirin in Japan, it was a benevolent animal, with shiny scales like a dragon and one or perhaps two horns. It avoided fighting and walked so softly that it would not disturb or harm a blade of grass. An animal like this (probably the saola) is most likely the one referred to in stories in North Korea. In 2012, North Korea announced that its archeologists discovered a unicorn lair. Yeah.

The Very Real Narwhal

However, back to the real world. Most likely, those horns in the Roman markets were narwhal tusks, as discussed in a 2011 paper. It is very likely that the narwhal played into the unicorn legend, as their tusks could be offered as concrete proof of “unicorn” existence.

The narwhal (Monodon monoceros) is an amazing animal that abandoned bilateral symmetry. In fact, monodon means one tooth, and monoceros means one horn; a pretty accurate name, all in all.

Narwhals are a species of whale, like blue whales and humpback whales, meaning that they are mammals. They live way up north. From the Baffin Bay, around Greenland, to the north of Russia, they swim in pods of 10-100, but you’ll rarely see them even if you live near there. There are perhaps 45,000-50,000 narwhals today.

This is a steady number because it is so hard to get to where they live. Consequently, narwhals have not been hunted to extinction. They spend a lot of their time on deep dives under the ice floes, so they are not seen often. No narwhal has ever been seen feeding. We only know what they eat from examining stomach contents.

The Narwhal Tusk is a Tooth

Their most distinctive feature is the long tusk (up to 10 ft, or 3 m) on the males. Just one tusk, mind you, like a unicorn horn. The narwhal’s tusk—like the elephant’s, walrus’s or warthog’s tusks—is a tooth.

Very young narwhals have six tooth buds in the upper jaw (maxillary) and two pairs of tooth buds in the lower jaw (mandible). However, only one pair develops any further. A tooth bud is what you find on an X-ray of a child.

Teeth form in the jawbones as tooth buds. Most narwhal teeth never go past the tooth bud stage, but occasionally a tooth will erupt where one shouldn’t. These are often misshapen or caught between the bone and the palate, or in the wrong place. This is all good evidence that the teeth are vestigial: they serve no functional purpose for the normal narwhal.

RELATED: NARWHAL TUSKS EXPOSE CLIMATE CHANGE

Just one tooth, almost always the left cuspid (most people call it a canine), does develop. Hold on though. It is not that simple. Instead of developing in a vertically directed tooth bud and erupting down through the jaw, the left canine stays horizontal and erupts right through the front of the jaw and through the narwhals lip!

Since the tusk is derived from the left cuspid, it erupts left of center, making the narwhal bilaterally asymmetric! A 2012 study showed that the bony attachment and length proves that the narwhal tusk is a canine, not an incisor as so many people think. But, it is not just the location that makes the narwhal tusk amazing, it is how it is made and what it can do.

A 1988 study suggests that the tight spiral keeps the tusk from curving as it grows. A curved tusk would make it hard of the narwhal to swim in a straight line. Whatever the reason, the spiral is an iconic image for both narwhals and unicorns.

Deep Inside the Narwhal’s Tusk…We Mean Tooth

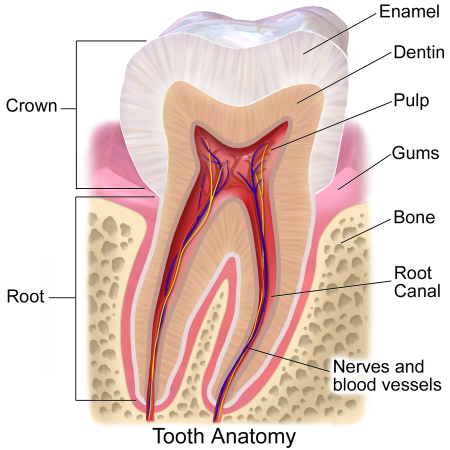

Teeth are normally built with the hard enamel on the outside. Enamel is harder than bone and protects the teeth from breakage when chewing. The mouth is a rough environment and teeth have to put up with a lot of abuse.

Deep to the enamel is a material called dentin. This stuff has many similarities to the bone, although it is not quite as hard and does not have living cells within it (like osteocytes). The dentin does contain millions of tubules that go from the enamel junction all the way to the pulp in the center. The pulp has a nerve and blood vessels.

The dentinal tubules have fluid and small processes of the neuron in them. When you eat something cold or have a cavity, the fluid in these tubules moves and changes the pressure in the pulp chamber. The single neuron in the tooth is a pain neuron, so your brain interprets as pain any pressure change. It teaches you to take care of your teeth, but it is not the most pleasant of all evolutionary adaptations.

The narwhal’s tusk is different. It is the only tooth known that has the dentin on the outside, although a 1987 study showed that it has no enamel, so it is not really an inside out tooth. The dentin is covered by a thin layer of cementum. This is what normally covers the roots of the teeth and helps attach them to the bone. The dentin of the narwhal’s tusk has about 10 million of those tubules, but it is different from human dentin.

A 1990 study compared calcium content and hardness between human teeth and narwhal tusks. The narwhal tusks’ cementum was more mineralized than that of human teeth, but the dentin of narwhal tusks was softer and less mineralized than human dentin. This may be why the narwhal’s tusk is so flexible.

The tubules of the narwhal tusk dentin connect to channels in the cementum, so there is a communication to the outside. A group in 2014 showed that narwhal’s heart rate changed when the water touching their tusk was switched from freshwater to saltwater. Therefore, they hypothesized that the tusk is a mechanosensor, in other words it senses temperature, salinity, pressure, and perhaps touch to help in navigation and hunting.

However, if that is the case, why do only males have them? Females have to hunt too. The group from the 2014 paper offers that males and females have sexually dimorphic foraging techniques—they eat different things and hunt differently, so females do not need horns. This hypothesis is not well supported. In fact, other scientists believe the long tusk is a sign of health and genes and is therefore an ornament for mate selection.

Occasionally, one will see females with a tusk, but like in other species (such as elephants), the female tusks are usually shorter. You can also find narwhal males with two tusks. But two tusks does not mean that they are returned to bilateral symmetry. Both tusks spiral to the left! There must be some strong left-hand genes at work.

One last thing. The narwhal’s offset tusk leads to another weird behavior. A group in 2007 put cameras and positional monitors on some narwhals and found that they tend to swim upside down a lot. Almost 70 percent of their time on the ocean floor was spent in the supine position. Since the tusk points down just slightly, scientists believe they hunt upside down so that the tusk will not get stuck in the ocean floor and break! The tusk must be pretty important, or they just like lounging on their backs.

References

Christen AG, & Christen JA (2011). The unicorn and the narwhal: a tale of the tooth. Journal of the history of dentistry, 59(3), 135-42 PMID: 22372187

Kingsley, M., & Ramsay, M. (1988). The Spiral in the Tusk of the Narwhal ARCTIC, 41 (3) DOI: 10.14430/arctic1723

Nweeia, M., Eichmiller, F., Hauschka, P., Donahue, G., Orr, J., Ferguson, S., Watt, C., Mead, J., Potter, C., Dietz, R., Giuseppetti, A., Black, S., Trachtenberg, A., & Kuo, W. (2014). Sensory ability in the narwhal tooth organ system The Anatomical Record, 297 (4), 599-617 DOI: 10.1002/ar.22886

Dietz, R., Shapiro, A., Bakhtiari, M., Orr, J., Tyack, P., Richard, P., Eskesen, I., & Marshall, G. (2007). Upside-down swimming behaviour of free-ranging narwhals BMC Ecology, 7 (1) DOI: 10.1186/1472-6785-7-14

About the Author

Mark Lasbury, MS, MSEd, PhD is a science and history writer based in Indianapolis, IN. He is the author of more than fifty peer reviewed scientific articles, two textbook chapters concerning molecular diagnostics in hematology, and several articles on local Indiana history. He has taught life sciences at the secondary, college, graduate, and post-graduate levels, authors a life sciences education blog, As Many Exceptions As Rules, and is co-founder of the pop culture science blog, The ‘Scope. His book on the research bringing Star Trek technologies to the real world will be published in mid-2016 by Springer Publishing.