NOAA has announced that the third global coral bleaching event is underway. Find out what you might be able to do to help save the coral reefs.

By Kate Stone

Waters are warming in the Caribbean, threatening coral reefs in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, scientists report. As record-high ocean temperatures cause widespread coral bleaching across Hawaii, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) scientists have confirmed that the same stressful conditions are impacting the Caribbean and may last into 2016, prompting the declaration of the third global coral bleaching event ever on record.

What is Happening to the Coral Reefs?

“Last year’s bleaching at Lisianski Atoll was the worst our scientists have seen,” says Randy Kosaki, NOAA’s deputy superintendent for Lisianski Island and Papa‘āpoho Marine National Monument. “Almost one and a half square miles of reef bleached last year and are now completely dead.”

Coral bleaching occurs when corals are exposed to stressful environmental conditions, such as high water temperature. Corals expel the symbiotic algae living in their tissues, causing them to turn white or pale. Without the algae, the coral loses its major source of food and is more susceptible to disease and death.

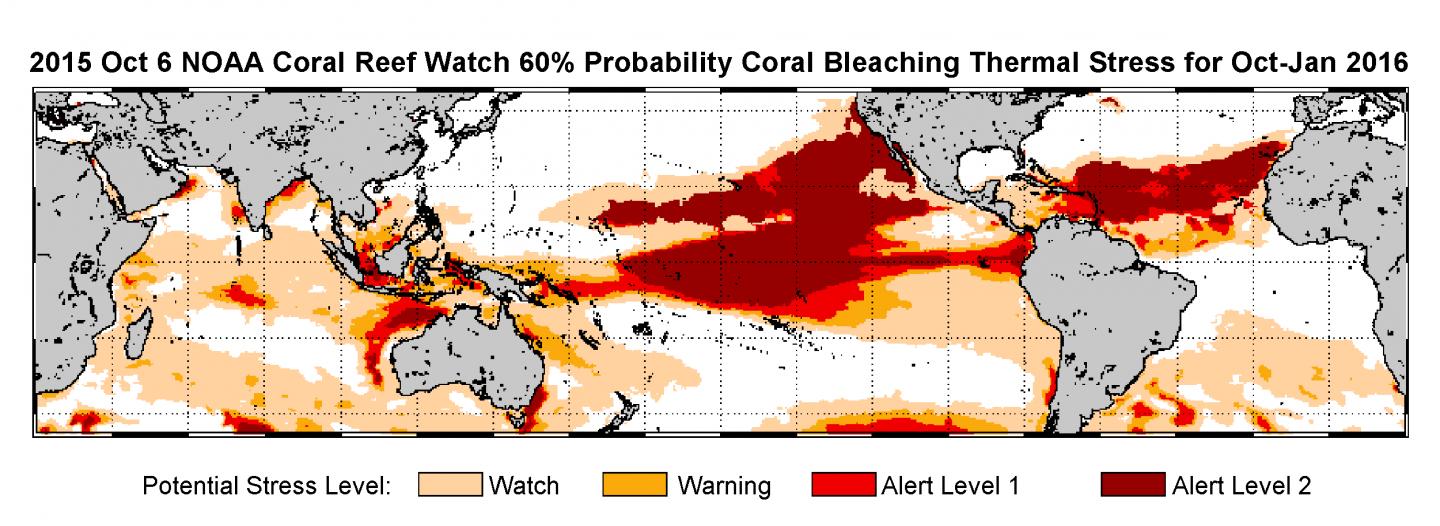

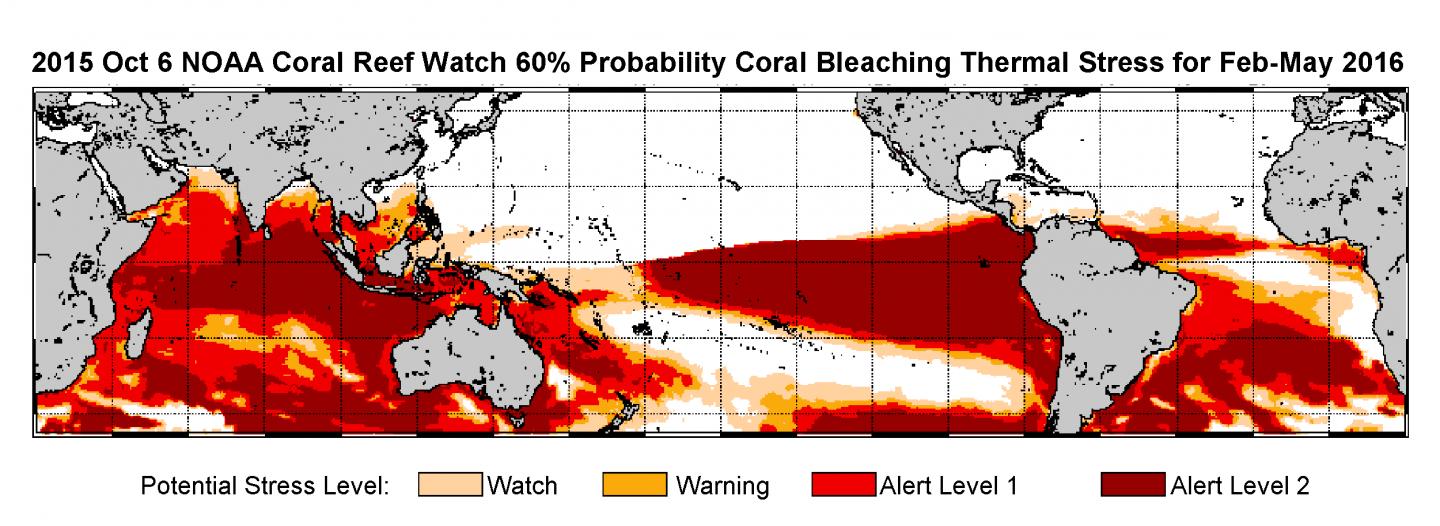

“The coral bleaching and disease, brought on by climate change and coupled with events like the current El Niño, are the largest and most pervasive threats to coral reefs around the world,” says Mark Eakin, NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch coordinator. “As a result, we are losing huge areas of coral across the United States, as well as internationally. What really has us concerned is this event has been going on for more than a year and our preliminary model projections indicate it’s likely to last well into 2016.”

Healthy coral reefs can absorb environmental pollution, but increased water temperatures are a death knell. While corals can recover from mild bleaching caused by increased water temperatures, severe or long-term bleaching is often lethal. After corals die, reefs quickly degrade and the structures erode away. As a result, shorelines lose their protection from storms and marine animals lose their habitats.

This bleaching event, which began in the North Pacific in the summer of 2014 and expanded to the South Pacific and Indian oceans in 2015, is hitting U.S. coral reefs disproportionately hard. NOAA estimates that by the end of 2015, almost 95 percent of U.S. coral reefs will have been exposed to ocean conditions that can cause corals to bleach and possibly die.

The biggest risk right now appears to be to corals in the Hawaiian Islands. Areas at risk in the Caribbean include Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Puerto Rico.

Scientists are concerned about the further impact of the strong El Niño conditions, which they expect to add to the stress on coral reefs.

What Can We Do About Coral Bleaching?

“We need to act locally and think globally to address these bleaching events. Locally produced threats to coral, such as pollution from the land and unsustainable fishing practices, stress the health of corals and decrease the likelihood that corals can either resist bleaching, or recover from it,” explains Jennifer Koss, NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program acting program manager. “To solve the long-term, global problem, however, we need to better understand how to reduce the unnatural carbon dioxide levels that are the major driver of the warming.”

RELATED: Help researchers protect marine animals by participating in one of these Indoorsy Citizen Science Projects.

The outlooks were developed jointly by NOAA’s Satellite and Information Service and the National Centers for Environmental Prediction, through funding from the Coral Reef Conservation Program and the Climate Program Office. More information about coral bleaching research is available from NOAA.

Explore more: Coral Reefs Versus Climate Change

Photo and coral bleaching outlook maps provided by NOAA.