Look into the eyes of moths and see the future. The future of smart gadgets, that is. Moths’ eyes are the latest inspiration for thin solar material. Researchers from the University of Surrey’s Advanced Technology Institute say that new, ultra-thin, patterned graphene sheets will be essential in designing “smart wallpaper” and other future technologies.

Graphene is traditionally an excellent electronic material, as the graphene-based microphone demonstrates, but it is inefficient for optical applications. It usually absorbs only 2 or 3 percent of the light that lands on it. That’s not very much. José Anguita of the University of Surrey explains, “As a result of its thinness, graphene is only able to absorb a small percentage of the light that falls on it. For this reason, it is not suitable for the kinds of optoelectronic technologies our ‘smart’ future will demand.”

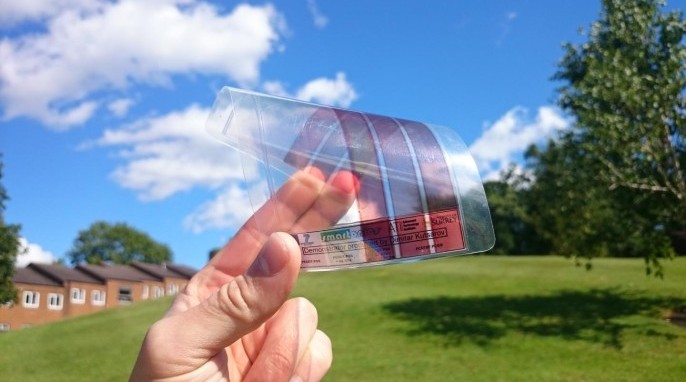

Recently, research teams at several universities have been enticed by the potential of graphene. Our own Jonathan Trinastic recently reported on graphene caught behaving like a liquid. Meanwhile, the University of Surrey’s research team has been busy manipulating graphene to create the most light-absorbent material for its weight, ever. This nanometer-thin material absorbs 90 to 95 percent of the light that strikes it, and could enable future applications such as “smart wallpaper” that could generate electricity from waste light or heat and power a host of applications in the growing internet of things.

What is the Internet of Things?

The Internet of Things (IoT) is the digital network of physical objects—devices, vehicles, buildings, and other items equipped with software, sensors, and network connectivity. The network enables smart objects to collect data, exchange information, and respond to the environment.

What Happens to the Graphene?

The University’s team, inspired by the tiny textures of the eyes of moths, are using a technique known as nanotexturing, which involves growing graphene around a textured metallic surface to create ultrathin graphene sheets. Just one atom thick, graphene is very strong but traditionally inefficient at light absorption. By using nanotexturing to aim light into the material, the team has increased the light-absorbing power by about 90 percent.

“Nature has evolved simple yet powerful adaptations, from which we have taken inspiration in order to answer challenges of future technologies,” explains Ravi Silva, head of the Advanced Technology Institute. “Moths’ eyes have microscopic patterning that allows them to see in the dimmest conditions. These work by channeling light toward the middle of the eye, with the added benefit of eliminating reflections, which would otherwise alert predators of their location. We have used the same technique to make an amazingly thin, efficient, light-absorbent material by patterning graphene in a similar fashion.”

RELATED: NEW GRAPHENE MICROPHONE OUTPERFORMS NICKEL

Graphene has already been noted for its remarkable electrical conductivity, but until recently it could not harness light and heat effectively. “Solar cells coated with this material would be able to harvest very dim light. Installed indoors, as part of future ‘smart wallpaper’ or ‘smart windows,’ this material could generate electricity from waste light or heat, powering a numerous array of smart applications. New types of sensors and energy harvesters connected through the internet of things would also benefit from this type of coating,” Silva says.

What’s Next for Graphene in Consumer Tech?

The researchers are excited about applying the potential of graphene to existing and new technologies. Devices with screens, such as smartphones and tablets, could soon be retrofitted with a graphene overlay. It could also be used to create smart wallpaper and smart windows, like these. “The next step is to incorporate this material in a variety of existing and emerging technologies,” says Silva. With that next step in mind, the researchers are looking for industry partners to help deliver the power of graphene to the public.

The team from the University of Surrey’s Advanced Technology Institute developed this technology in cooperation with BAE Systems. The research is published in the journal Science Advances.