Researchers from the University of Hawaii at Manoa show us what ocean life is like atop a deep sea mountain.

For all of humanity’s technology and scientific accomplishments, the deep sea still remains one of the most mysterious, unexplored regions on Earth.

But a team of researchers from the University of Hawaii at Manoa captured a glimpse of what abyssal ocean life is like atop a deep sea mountain and published their findings earlier this month.

New terrain

About 75% of the ocean floor is “abyssal,” or between 3,000 to 6,000 meters below the sea’s surface. And far below the Himalayas, Rockies and Sierra Nevada that we know are “abyssal seamounts,” or mountains with summits 3,000 meters below the ocean’s surface.

These deep sea mountains—and the plains surrounding them—are some of the least studied environments on the planet. Not only are they difficult to access, but according to much of the existing research, these areas are sparsely populated and offer scarce food supply for the organisms that do live there, offering little incentive to make the effort.

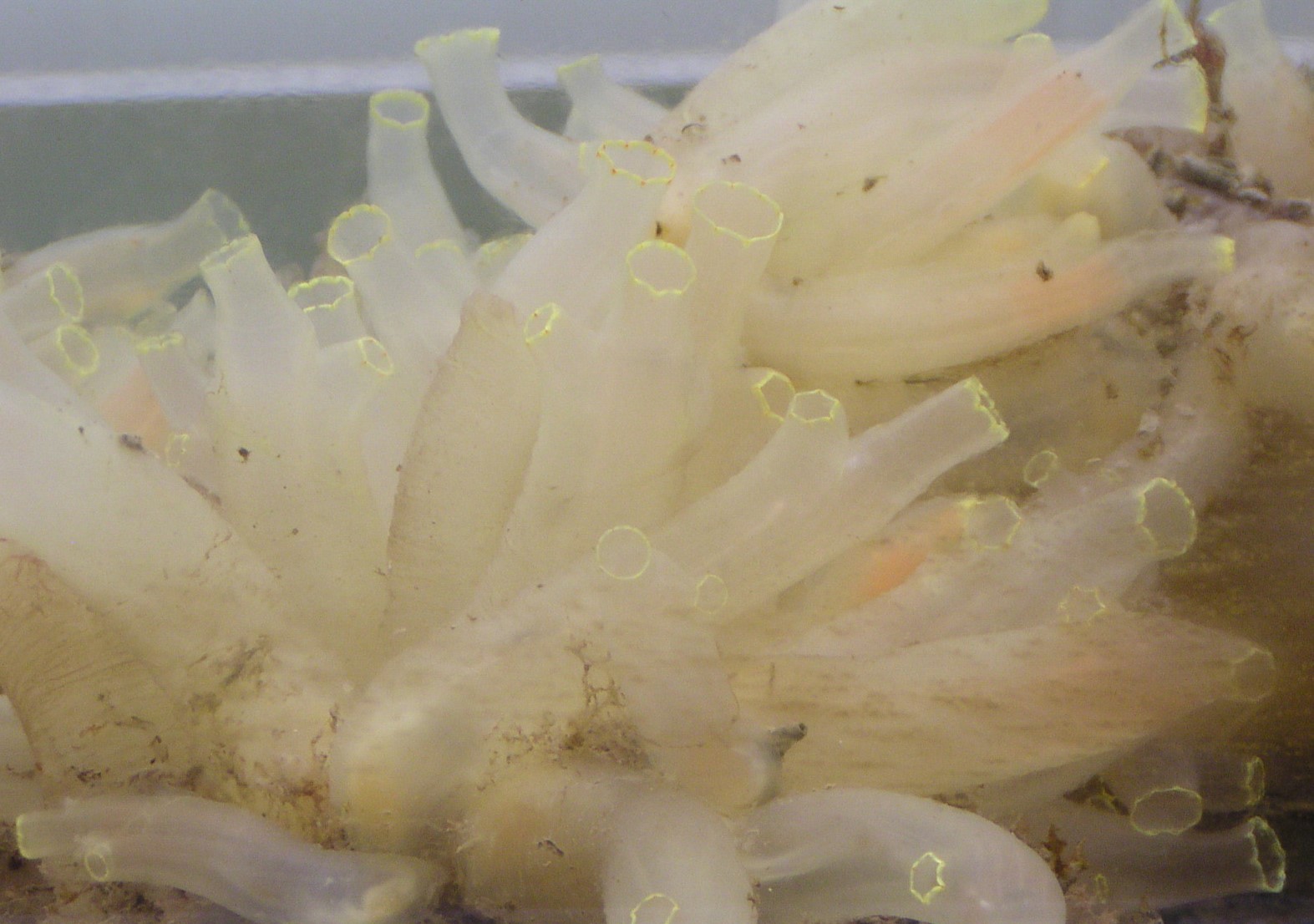

However, new evidence from a team of oceanographers suggests we may need to dive a little deeper to see what else is really down there. They have recorded the largest group of fish ever seen in such an environment.

RELATED: Undiscovered Species of the Deep Sea: Can We Find Them?

A different approach

Joined by oceanographers from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute and the United Kingdom’s National Oceanography Centre, the University of Hawaii researchers made their observations while on an expedition in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), a swath of the ocean floor in the central Pacific Ocean between Mexico and Hawaii. This area is being investigated for deep sea copper, cobalt, zinc and manganese mining, so the research team was tasked with surveying three of the CCZ’s underwater mountains and the nearby plains to see what, if anything, lived there.

Since many species that far down in the ocean naturally avoid light and noise, the team used baited camera stations to make their observations. Cameras, as opposed to traditionally used research vessels, can remain unobtrusive, while baited stations mimic how animals in the abyss typically find their food: by scavenging large chunks of dead sea animals that sink to the ocean floor.

RELATED: Carbon Isotope Anomaly in the Deep Sea

In results that were “truly surprising,” according to Astrid Leitner, the research team ended up finding abundant life in the deep, when more than 100 cutthroat eels swarmed a bait package at the top of one of the CCZ’s underwater mountains. This is more than twice the previous record of fish recorded at one time at these depths. It’s also the largest group of fish ever recorded below 1,000 meters beneath the surface—including those feeding on large carcasses like those of whales or sharks.

Deep sea discoveries

Using a baited trap, the researchers caught a few of the eels for identification and determined the species was Ilyophis arx. With fewer than 10 specimens in collections across the planet, little is known about Ilyophis arx, allowing the research team to contribute even more information to their field with one study. To make matters all the more intriguing, the three seamounts sampled in this study were previously unexplored and unmapped.

RELATED: INTRODUCING FIVE NEW DROWNED APOSTLES

As of yet, the researchers aren’t sure exactly why the eels were swarming the seamount’s summit. The study notes that the eels were not found on the abyssal plains below, but only at the peak of the seamount, leading the team to believe an “abyssal seamount effect” could be at play — in other words, the mountain peaks are more habitable to deep sea fauna than other areas in the abyss. They also suggested the gathering might have been a temporary spawning event, though none of the 12 eels they captured were pregnant females, so they note this explanation is unlikely.

FIND OUT HOW MOUNTAINS FORM: Mountains Form Between, Not During, Earthquakes

Treading carefully

Leitner asserts that this study could have huge implications, not only for life on the rest of the seafloor and its underwater peaks, but for industry’s explorations in the deep blue sea. Assuming the findings aren’t limited to the seamounts studied in the CCZ, who knows what other animals are living at those depths? What might we still find and study—and what could we harm without even knowing it?

“Our findings highlight how much there is still left to discover in the deep sea, and how much we all might lose if we do not manage mining properly,” Leitner says.

This study was published in the journal Deep Sea Research.

Reference

Leitner, A. B., Durden, J. M., Smith, C. R., Klingberg, E. D., & Drazen, J. C. (2020). Synaphobranchid eel swarms on abyssal seamounts: Largest aggregation of fishes ever observed at abyssal depths. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 103423. doi:10.1016/j.dsr.2020.103423

Featured photo: Cutthroat eels (Ilyophis arx, Family Synaphobranchidae) swarming at a small bait package deployed on the summit of an unnamed abyssal seamount in the southwestern Clarion Clipperton Zone at a depth of 3083 m. Courtesy of Deep Sea Fish Ecology Lab, Astrid Leitner and Jeff Drazen, Department of Oceanography, SOEST University of Hawaii Manoa, DeepCCZ expedition.

About the Author

Mackenzie Myers Fowler is a science writer, native Michigander, and former field station ragamuffin. She holds an MFA in nonfiction writing but would be a soil scientist if she could do it all over again.