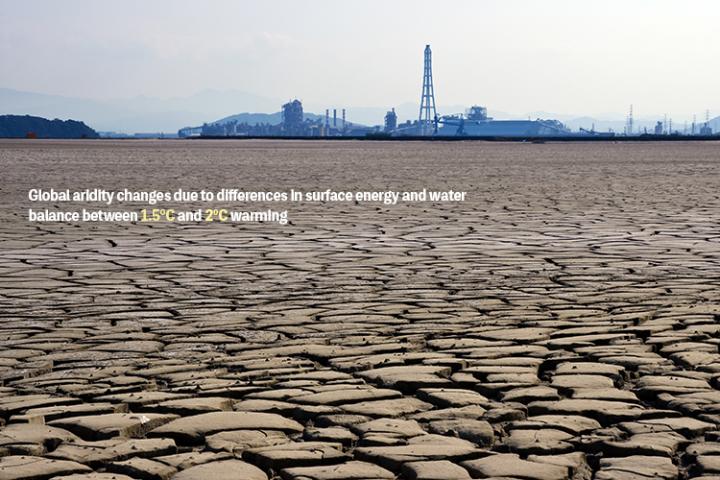

Climate change is here and it’s not good. The very near future promises to be hotter and dryer in some places. Find out what the numbers really mean.

By Jessica Breavington

International climate change negotiations have set a 1.5 to 2 degree limit for global warming. A couple degrees of heat might not seem like much, but there are big differences in dryness between 1.5 and 2 degrees of warming, with lots of variability between countries. Using complex climate-simulation models, researchers at the University of Tokyo explored what reaching these temperature targets mean, and how 1.5°C and 2°C warming will have very different effects on the amount of rainfall regions get, known as aridity. Changes in aridity have severe implications for ecosystems, agriculture, and water availability. Researchers highlight how very weak levels of warming, like an additional 0.5°C on top of the 1.5°C limit set through international agreement, will have major effects in some parts of the world.

Why may an extra 0.5°C warming be so significant?

When it became clear global warming was a significant threat, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) decided to try and limit the temperature increase to 1.5 or 2°C above pre-industrial temperatures. However, these targets were made with a heavy consideration of what was achievable, rather than what was required to minimize the damage to natural systems and the impacts on human society. In 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) published a report discussing the relative impacts of 1.5 and 2°C of warming. Despite this, there has been a lack of research into the underlying climate mechanisms at these relatively small temperature increases. Researchers at the University of Tokyo address this using a specially designed model to distinguish between the differences of 1.5 and 2°C.

- Global warming can have complex effects on climate. Researchers in this study have chosen to focus on aridity changes, specifically:

- Global-scale changes to aridity and the role of net radiation and precipitation

- Regional aridity changes and determining the primary cause as net radiation or precipitation changes

- Changes in the frequencies of severe dry years

It is clear how precipitation affects aridity. More rain will make an area less arid, and less rain will increase aridity. Researchers also focus on net radiation because it can measure the greenhouse effect. The greenhouse effect is caused by carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gasses trapping the sun’s heat in the Earth’s atmosphere and reducing the amount of sunlight getting reflected into space. This affects the water cycle as higher temperatures increase evaporation. However, because the water cycle is a closed system, the Earth can never gain or lose water, it is just stored in different forms, whether that is in ice, as vapor in the atmosphere, or as sea water. Consequently, this means increased evaporation in one area results in increased rainfall elsewhere. Together, net radiation and precipitation form something called the hydroclimatic regime which can help us understand water-balance. When the hydroclimatic regime shifts, it results in changes to dryness and aridity. Aridity and drought have huge impacts on agriculture, ecosystems, water distribution, and human society. It is essential that we understand how the complex processes behind an additional 0.5°C warming can have a significant effect on one of the most important climatic processes.

What do climate change models mean?

Most climate models cannot distinguish between the differences caused by an extra 0.5°C of warming for individual countries. This is because most models consider the effects of an average global temperature. This study is different because it considers the effects of a 0.5°C temperature increase for different regions. In reality, 1.5 or 2°C average warming will result in some places being much hotter than the average increase, and other places experiencing very little increase. By using climate projections based on the Half a degree Additional warming Prognosis and Projected Impacts (HAPPI) project, the researchers have overcome this challenge. The HAPPI project is suitable for a large number of samples which is required to make the whole model accurate, it considers how the climate is non-linear – meaning a small additional increase in one thing can result in a big increase in another, and considers scenario dependency – that something may not happen in one area, unless a different thing happens in another area. Overall, the HAPPI project estimates surface energy and water balance, and the hydroclimatic mechanisms of aridity changes on a global scale.

Also used in the study is the Budyko dryness index which simply groups areas into seven categories based on dryness. The precipitation and net radiation changes simulated by models can be used to calculate the new Budyko dryness index of countries if either warming target becomes a reality. Excluded from this study are Antarctica, Greenland, and hyper-arid regions due to the limits of the models, as these places will be more likely to experience the most extreme effects of warming.

Effects of a 1.5°C vs 2°C increase

While the geographical distribution of the changes caused by the climate remain largely the same between 1.5°C warming and 2°C warming the severity of the impacts varies which is the most likely to cause bigger problems for people and ecosystems. Below, the main findings for each continent is summarized. However, intra-continental variability tends to be greater than inter-continental variability. This means that differences within continents are greater than differences between continents. This is because aridity is more likely to correspond to latitudes rather than landmasses. For example, in America, the desert regions of the south-west are of course much more arid than the Southern states like New York and there are huge variations in the climate across the country.

Antarctica

This continent is excluded along with Greenland and hyper-arid regions.

Africa

Africa shows complex patterns. Southern Africa will experience significant aridification and become much drier. This study indicates the Sahel will become drier but previous research contradicts this and has predicted for the Sahel to become wetter. The Horn of Africa will become wetter under both temperature increases. Unfortunately, precipitation is a major source of uncertainty in climate models as the hydrological cycle is influenced by many factors rather than just temperature. For some regions, the decrease in precipitation in the cause, and other regions the increase in net radiation is the primary cause. The results cannot be broken down into two broad trends. Although one thing is clear; the parts of Africa becoming more arid will have less aridification under 1.5°C of warming. With dry-year frequency, central Africa has one of the most severe increases. The dry-year frequency does not mean an increase in individual-drought disasters, but rather the steady-state of the climate system, and what is predicted to become the ‘new-normal’.

Asia

East Asia, excluding the southern part of China will experience a trend toward wetter weather. India is another country which will experience a wetting trend which is also more severe under a 2°C increase. This is because India is already within a wetting area which has high amounts of rainfall. Parts of Eurasia experience a decrease in aridity from 1.5 to 2°, because of rapidly increasing precipitation with the 0.5°C temperature increase. Countries such as Russia, and former Soviet republics are generally agreed to fall under the category of Eurasia.

Australia

The east coast of Australia will experience aridification. One of the more complex trends is that there is a non-linear trajectory towards a wetter climate after warming exceeds 1.5°C, with a lesser temperature increase there is a drying trend. Although researchers are uncertain about the underlying cause of this trend three out of the four climate models show the same result indicating the data is robust. One possible explanation is a change to the Australian monsoon circulation.

Europe

There is much focus on the Mediterranean region. This is because significant aridification from current temperatures to 2°C warming is predicted over the Mediterranean. Out of all the regions, a section of the Mediterranean coast is predicted to experience the biggest increase in aridification with the additional 0.5°C warming. The models also show the mechanisms driving the aridification very difference between 1.5 and 2°C warming. Like the increases in aridity to the Mediterranean, there is only a weak increase in dry year frequency under 1.5°C warming, but with the extra 0.5°C warming, dry-years will become twice as frequent.

North America

For North America both net radiation and precipitation shifts mean a drier climate in the southern and north western states. This occurs under 1.5°C warming as well as 2°C. However, substantial areas will become less arid because of rapidly increasing precipitation. In terms of dry year frequency, the east of North America will have less frequent dry-years with 2°C warming compared to 1.5°C, showing an increase in temperature does not always mean dryer years. In general, dry conditions will be 10%-50% less frequent in all regions of North America except the east coast.

South America

The northern parts of the continent will experience significant aridification. A decrease in precipitation is the driving factor for the aridity increase from 1.5 to 2°C, with changes in net radiation having little influence. For many regions, the change between current temperatures and 1.5°C of warming is roughly the same as the change between 1.5°C warming and 2°C. This demonstrates that effects are non-linear and can get exponentially worse with seemingly small increases. The north of South America also will experience extremely dry years more than two times more frequently under 1.5°C warming, than without warming. With 2°C of warming this will become even more frequent.

Global climate change impact

The most significant increases in drying trends are seen in northern South America, the Mediterranean, Southern Africa, the Sahel, Southeastern Asia, and Australia. However, increases in precipitation in the Sahel, Southeastern Asia, and Australia between 1.5 and 2°C may counteract the aridity intensification predicted between pre-industrial temperatures and 1.5°C warming. A 2°C increase will mean more frequent dry years and more severe aridification for most of the Earth’s landmasses but projected warming does not always lead to a drier climate or more frequent dry conditions, like in the case of Australia, and where wetter conditions are forecast for areas under both 1.5°C and 2°C increases. Certainly, the impacts of the additional 0.5°C warming will be much more severe in some areas than others, making it all the more important to evaluate these changes carefully, especially in regions such as Central Africa with vulnerable populations.

This study was published in the journal Environmental Research Letters.

Reference

Takeshima, A., Kim, H., Shiogama, H., Lierhammer, L., Scinocca, J. F., Seland, Ø., & Mitchell, D. (2020). Global aridity changes due to differences in surface energy and water balance between 1.5° C and 2° C warming. Environmental Research Letters, 15(9)

Featured photo: “Cracked Earth” by Antoine Collet

About the Author

Jessica Breavington is a student at Durham University studying Natural Sciences in biology, geography, and earth science. As an extensive traveler, she has observed first-hand the human impacts on the environment and the effect of climate change on the natural world. She writes more about her studies and experiences in her blog at www.anthroment.com.