By Mackenzie Myers, @kenzwrites

Quiet as a mouse. Timid as a mouse. When’s the last time you heard a mouse described as brave?

The scientific community has already established that a parasite carried by cats and their feces, Toxoplasma gondii, causes infected mice to lose their fear of feline predators. But a new study from researchers at the University of Geneva and the University of Toronto points to a decrease in anxiety that may be less specific than previously thought, giving mice a one-size-fits-all fearlessness.

What is Toxoplasmosis?

T. gondii, which can infect most species of warm-blooded animals, including humans, causes the disease toxoplasmosis. According to a press release on this new study, an estimated 40 million people in the U.S. alone carry this single-celled parasite. However, unlike mice, humans rarely exhibit symptoms.

Still, the disease is a leading cause of foodborne illness–related deaths in the U.S. and can cause fetal deaths if a person contracts it while pregnant. Even while it’s dormant, toxoplasmosis can increase the chances of suicide attempts and mental illnesses like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

Though humans’ symptoms from a toxoplasma infection are different from those of infected mice, learning how the infection affects mice can help us understand more about neurological behaviors and perhaps gain insights on neurodegenerative diseases that affect our species.

Fatal attraction

One of this new study’s seven co-authors, Ivan Rodriguez of the University of Geneva, says that the toxoplasma parasite causes significant changes in brain activity of infected mice, altering behaviors and overall neural function. It leads to a more relaxed, curious, trusting version of how we typically picture mice: skittish, alert, and overly sensitive to potential threats.

Past studies describe this phenomenon as “fatal feline attraction,” where mice infected by toxoplasma feel less afraid of cat odors and perpetuate a cycle: since they’re more courageous than those who are uninfected, they are easier to catch, get eaten, and are unwittingly helping to spread the parasite to other mice through cat feces.

Brave new world

This study in particular is significant because it points to a crucial flaw in the long-held “fatal feline attraction” theory: that “feline” isn’t necessarily a component. Infected mice in the study showed more curiosity in general, even when felines weren’t part of the picture. They spent more time in the open areas of an elevated plus maze (a raised structure with open and enclosed “arms” used to evaluate levels of anxiety during experiments), showing more interest in exploring new environments than those without T. gondii.

While their uninfected counterparts ran and hid in the looming presence of a researcher’s hand, toxoplasma-infected mice not only appeared unfazed, but interacted with the hand through touch and investigation.

Further exploring the idea of feline-specific attraction, the researchers conducted other tests using the smells of different animals. Past studies have shown that infected mice are not only willing to investigate bobcat urine but are attracted to it, whereas uninfected mice can take it or leave it. But in this study, the researchers used odors from guinea pigs and foxes, finding that the infected mice showed no preference for the smell of bobcats; they investigated the smells of other animals, too.

The researchers even anesthetized a live predator—a rat—which invoked fear in uninfected mice, but was just another opportunity to explore for those with T. gondii in their systems.

Inflammatory responses to toxoplasma infection

So how does the toxoplasma parasite actually cause these changes to take place?

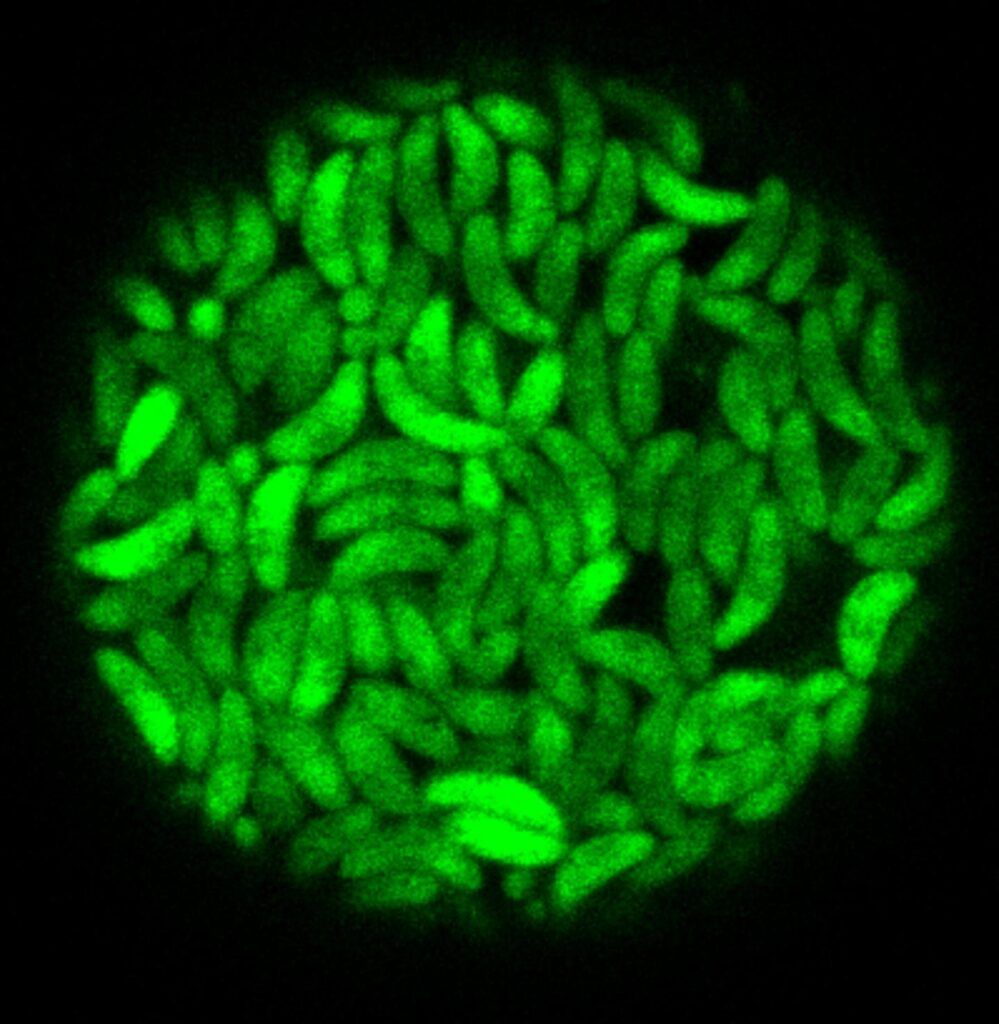

The long-held idea is that T. gondii manipulates a mouse’s brain in specific regions that respond to the presence of cats. Digging deeper in this study, the researchers mapped the brains of mice that had been infected for 10 to 12 weeks, tracking cysts that formed after infection. Their analysis showed that parasite-filled cysts developed more densely in the outer layers of the brain and in regions that process visual information. Mice with more intense behavioral changes tended to have higher levels of inflammation and more cysts.

The researchers now believe that changes in behavior are spurred by inflammation of neurons, rather than the parasite itself interacting with the neurons, and that when studying the effects of the parasite, the host’s level of infection is important to consider.

Creature caveats

Continuing to explore this new idea, the researchers hope to examine how inflammation of tissue in the nervous system can impact anxiety, curiosity, and other traits. Since T. gondii affects humans and mice so differently, the team cautions in the study that a direct comparison of the two hosts would be ill-founded. But they go on to say that inflammation of the central nervous system has a clear impact on behavior and, within the right context, studies like this may even help us better understand neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s.

However, given the differing levels of impact between the two mammals, it’s not quite the same.

“We hope that people understand that they will not get the ‘crazy cat lady syndrome’ if they are infected with T. gondii,” Soldati-Favre says.

This study was published in the journal Cell Reports.

Featured photo: Wood mouse, photographed by Paul Gulliver (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Reference

Boillat, M., Hammoudi, P. M., Dogga, S. K., Pagès, S., Goubran, M., Rodriguez, I., & Soldati-Favre, D. (2020). Neuroinflammation-associated aspecific manipulation of mouse predator fear by Toxoplasma gondii. Cell Reports, 30(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2019.12.019

About the Author

Mackenzie Myers is a science writer, native Michigander, and former field station ragamuffin. She holds an MFA in nonfiction writing but would be a soil scientist if she could do it all over again.