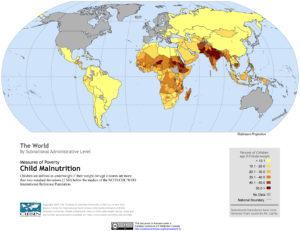

Malnutrition affects hundreds of millions of children around the world. Scientists think lipid-based nutrient supplements might help.

Malnutrition affects hundreds of millions of children around the world. As of 2017, about 23 percent of children younger than five suffer from stunted growth because of malnutrition and about 8 percent experience extreme wasting, which is characterized by a low weight-to-height ratio. Although over the years many treatments have been developed that reduce chances of mortality, increase weight gain, and improve lean tissue creation—all signs of healthy development—more work is necessary to create an inexpensive, accessible, and long-term solution.

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF; also known as Doctors Without Borders), as well as DANIDA and others, funded a study in Burkina Faso in West Africa to test the effectiveness of various lipid-based nutrient supplement (LNS) made primarily of peanut butter. The research group included a team of Copenhagen researchers led by Christian Fabiansen, as well as a PhD student from a local Burkinabe university and the medical NGO The Alliance for International Medical Action (ALIMA). The study compared LNS to corn-soy blend (CSB), a common supplement that has been shown to improve weight gain but doesn’t necessarily contribute to muscle mass or organ development.

RELATED: Eating Peanuts for Peanut Allergy Protection: A New Study

LNS has been used to treat moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) for some years, but there has been no consensus on whether it is more effective than CSB, or whether children who consume LNS as a treatment for malnutrition gain primarily fatty tissue or healthy, fat-free tissue (like muscles and organs). In this MSF-funded study, the researchers in Burkina Faso believe that LNS will not only help children put on weight, but the majority of that weight could come from proper muscle and organ development.

Malnutrition is more than “not eating enough”

A diet lacking in quality nutrients causes malnutrition. Therefore, while it’s true that eating a sufficient quantity of food is important for overall health, it’s especially important to maintain a diverse diet. Essential proteins, fats, vitamins, and minerals are particularly important for healthy development of young, growing children. Diets that do not provide the right blend of nutrients can lead to malnutrition.

Malnutrition is also a self-perpetuating affliction—those who are malnourished lose their appetites, thus causing them to consume even fewer calories throughout the day. This means it requires less energy to build non-fatty tissue (like muscle and organs) and gain mass. This also means the body relies more on its own energy stores, leading to further loss of mass.

Additionally, because the body is underdeveloped and using more energy than it is taking in, it becomes increasingly difficult to ward off infection or cope with external stressors. This leaves the body susceptible to additional morbidities. By weakening the immune system, malnutrition increases the risks of infectious disease, and in turn, infectious disease increases the risk of malnutrition. Thus, diets that don’t provide the right blend of nutrients can increase the risk of death from common childhood illnesses.

Not all malnutrition is the same. Some types of malnutrition develop from a lack of specific nutrients, like potassium or magnesium, and others result from excessive or inadequate calorie intake.

RELATED: Vitamin D: Is It the Newest Brain Food?

Treatment options: ready-to-eat therapeutic and supplemental foods

Moderate acute malnutrition typically affects large populations rather than manifesting as an isolated event. Treatment plans created to address an entire community typically include a specialized food program, and possibly additional supplementary rations given to particularly malnourished individuals (or those more likely to become malnourished). Patients are monitored over time, and rations are adjusted as needed. Additionally, providing highly nutritious food products can help prevent moderate acute malnutrition from deteriorating into severe acute malnutrition.

Specialized LNS products are derivatives of ready-to-eat therapeutic foods (RUTFs), which were designed for the treatment of severe acute malnutrition (SAM). According to Kevin Phelan, Nutrition Advisor with ALIMA, RUTFs were the first high-nutrient-density paste developed to treat SAM. Since it was first developed in the early 2000s, over three million children have been treated for SAM, partially because of the availability of RUTF.

Although RUTFs are effective treatments, it is beneficial to seek out more efficient treatments for less severe forms of malnutrition. An ideal alternative would offer greater convenience for those receiving treatment and for their families. Improved treatment options would mean improved development of fat-free tissue and improved weight gain, with reduced morbidity.

A look at all the options

Lipid-nutrient supplements address malnutrition before it becomes a life-threatening condition that requires RUTF. Designed to provide 50 to 100 percent of the day’s energy requirements, LNS supplements are given in smaller doses, partially because they are more concentrated. These smaller doses of products like NutriButter and Plumpy’Doz are not as expensive as RUTF.

Corn-soy blends are also an inexpensive option for treating malnutrition. However, while CSB ingredients cost less than LNS, the treatment can lack nutritional quality and be more costly to transport and store. Further, the weight that CSB recipients do gain is mostly superficial—their organs and muscles do not show significant development. A 2010 article published in Maternity and Child Nutrition found that CSBs provide less than 75 percent of the nutrients that infants need.

Scientists have been testing the efficacy of LNS for the past few years. A 2012 study conducted among 1,038 infants in the African country Chad found that those who took LNS “exhibited greater growth in height, lower prevalence of anemia, and less morbidity” than those who only subsisted on household foods. A Bangladesh-based trial in 2016 found that pregnant women who were given LNS gave birth to infants with higher birth rates than women who were given iron and folic acid. Nine trials conducted between 2009 and 2016, covering 10,000 children across seven countries, found that recovery rates of children given LNS were 8 percent higher than those taking CSB.

Research also indicates that food supplements are most effective at combating malnutrition when coupled with financial assistance, which enables families to purchase local foods that give children additional nutrients. LNS is not intended to be a meal replacement; it is an emergency supplement. Scientists hope to improve the success rates of LNS and similar products so that the problems associated with malnutrition can be eradicated more completely in a shorter time frame, for less money.

Testing a new treatment for malnutrition

In the MSF-funded study, the Copenhagen researchers wanted to find out whether there was any truth to the suggestion that LNS builds fat rather than muscle. The research is part of a project called Treatfood, an international initiative seeking to improve treatments for acute malnutrition through quality scientific research. Over a period of 12 weeks, they worked with 1,609 children in rural Burkina Faso to test the efficacy of LNS compared to CSB, both of which aid agencies commonly use. They also tested whether the ingredients used in CSB and LNS made a significant difference in their effectiveness.

Children between 6 and 23 months old were given 500 calories per day of either LNS or CSB. In order to test ingredient quality, Christian Fabiansen and colleagues created versions of LNS and CNS that were made with either soy isolate or dehulled soy, as well as versions that contained between 0 percent to 50 percent milk protein.

They assessed the results using a deuterium dilution technique for measuring fat-free mass. In simplified terms, this means the researchers gave the subjects a dose of an isotope (a type of atom). They would measure the amount of the isotope in the body, then the subject would eat LNS or CSB. Afterward, researchers would measure the amount of the isotope again. Fabiansen and his coauthors discovered that “children who received LNS experienced greater weight gain, and the large majority of the weight gain was healthy lean tissue.”

Compared to children who received CSB, those given LNS gained 9 percent more weight. However, this was mainly true for LNS containing soy isolate. Lipid-based nutrient supplements made with dehulled soy resulted in little improvement compared to the CSB made with the same ingredient. Higher levels of milk protein did lead to greater weight gain, though the increase was negligible at levels over 20 percent. Overall, lean mass gain and recovery rates were better in the groups given LNS.

New recommendation for aid agencies

In light of their findings, Fabiansen and his colleagues recommend that more aid organizations use LNS to treat moderate acute malnutrition. When made with high-quality materials, LNS showed a significant increase in efficacy.

Further, because the research was done in collaboration with global aid groups, such as MSF and ALIMA, this information can be quickly shared and applied where it’s needed most. This can enable the development and provision of high-quality LNS more quickly and for more areas.

Study coauthor Susan Shepherd, a pediatrician who heads ALIMA’s Operational and Clinical Research, said in a press release, “vulnerable children, no matter where they live, deserve the best medical and nutritional treatments available. Studies like Treatfood generate the evidence we need to make the best decisions with our patients.”

Interestingly, the LNS that performed best in this study was the one most similar to successful RUTF products. With this and similar results in mind, researchers are looking at ways to simplify treatment methods for both SAM and MAM using an RUTF with a similar structure. As more LNS products are tested, their value becomes more apparent. Continued collaboration between research institutes, humanitarian groups, and international aid groups will allow more LNS products to be tested and more children to be treated.

As coauthor Henriik Friis said, “the collaboration between researchers and humanitarian organizations means these findings can have immediate practical impact on field practice.” Research is ongoing, and the cooperation of policy makers and international groups makes progress possible to benefit millions.

Featured image by Melica/shutterstock.com.

References

Dewey, K. G., & Arimond, M. (2012). Lipid-based nutrient supplements: How can they combat child malnutrition? PLoS Medicine, 9(9), e1001314. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001314.

Gera, T., Pena-Rosas, J. P., Boy-Mena, E., & Sachdev, H. S. (2017). Lipid based nutrient supplements (LNS) for treatment of children (6 months to 59 months) with moderate acute malnutrition (MAM): A systematic review. PLoS One, 12(9), e0182096. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182096.

Fabiansen, Christian. Personal communication.

Fabiansen, C., Yameogo, C. W., Iuel-Brockdorf, A., Cichon, B., Rytter, M. J. H., Kurpad, A., . . . Friis, H. (2017). Effectiveness of food supplements in increasing fat-free tissue accretion in children with moderate acute malnutrition: A randomised 2 × 2 × 3 factorial trial in Burkina Faso. PLoS Medicine, 14(9), e1002387. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pmed.1002387.

Mridha, M. K., Matias, S. L., Chaparro, C. M., Paul, R. R., Hussain, S., Vosti, S. A., . . . Dewey, K. G. (2016). Lipid-based nutrient supplements for pregnant women reduce newborn stunting in a cluster-randomized controlled effectiveness trial in Bangladesh. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 103(1), 236–249. Available at: http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/early/2015/11/25/ajcn.115.111336.

Phelan, Kevain (Nutrition Advisor with ALIMA). Personal communication.

UNICEF, World Health Organization, & World Bank Group. (2017). Levels and trends in child malnutrition. Available at: https://data.unicef.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/JME-2017_brochure_June-25.pdf.