Scientists study variations in blubber thickness on Yangtze finless porpoises to see how water temperature affects blubber in different regions of the mammal’s body.

By Amelia Hersant

Marine mammals demonstrate a startling array of adaptations to their watery environment. Such adaptations are vital as these animals face a variety of challenges unique to this habitat, including maintaining their body temperatures.

Unlike seals and otters, cetaceans (marine mammals including whales, dolphins, and porpoises) do not have fur to help regulate their body temperature. Instead, they have blubber. This is the layer of fat located between their skin and muscles. For cetaceans, it is believed that blubber is the primary, possibly the only, temperature-regulating feature they possess.

To better understand this adaptation, Bin Tang and fellow scientists on a team in China worked at the Baiji Dolphinarium off the famous Yangtze River, conducting a study to analyze how the blubber thickness of Yangtze Finless Porpoises (YFPs) in human care changed with water temperature.

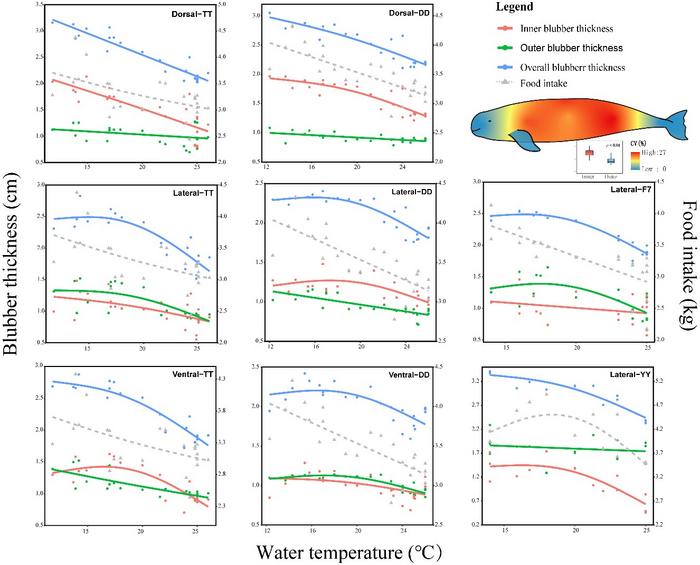

Not only did they identify correlations between blubber thickness and water temperatures, but they also found variation in blubber thickness at different regions on the porpoises’ bodies, suggesting different adaptive purposes.

Such research is vital within the context of climate change and concerns over increasing water temperatures which have the potential to significantly impact non-migratory species like the Yangtze Finless Porpoise, which lives solely in one habitat.

The study

The ethically approved study used four YFPs at the Baiji Dolphinarium (two males and two females). These YFPs were trained to lie on their right side without restraint, which allowed researchers to use an ultrasound to measure the blubber thickness at different points along their side once or twice a month for up to twelve months. Ultrasounds are favored for such studies due to their non-invasiveness and accuracy.

The blubber of cetaceans is divided into outer and inner layers. The outer section is anechoic (does not reflect sound) so shows up as a black space on the ultrasound image. The inner blubber, however, shows up as stratified layers. Both the outer and overall blubber thicknesses were measured.

These were then compared to the water temperatures, which were monitored daily and changed naturally between 11°C and 28°C (51.8°F to 82.4°F).

Blubber thickness of YFPs

As would be expected, blubber thickness was generally found to negatively correlate with water temperature; as water temperature increased, blubber thickness tended to decrease. The mean average blubber thickness was thickest during the winter months and thinnest over the summer.

Interestingly, they found that the blubber thickness varied at different sites on the YFP’s body. On the males, they measured nine different sites. Imagine the porpoise lying on its side and picture a horizontal line down the middle of its body from mouth to tail. This is the lateral region; the top is the dorsal and the bottom is the ventral. Now picture three vertical lines from the dorsal to ventral regions. These are the axillary, umbilicus, and anus (from head to tail, respectively).

They found that blubber thickness in the dorsal region changed most closely with water temperature and that this was dominated by changes in the thickness of the inner layer. Conversely, they identified that the lateral and ventral regions had a threshold: they did not change with water temperature until the temperature increased to 18°C (64.4°F).

Such differences suggest that the regions may have different adaptive purposes. What these are is highly controversial. Some scientists suggest that the more variable blubber in the dorsal region is due to this region’s function as an energy store. In contrast, other scientists suggest that the ventral region may be a more effective energy store due to its greater lipid (fat) contents.

The differences between inner and outer blubber thickness also indicate that the layers have differing roles. The inner layer appears more variable, suggesting that it is more dynamic when it comes to thermoregulation. The outer layer seems more consistent, indicating that it has more properties to do with structural support.

All of these possible explanations require further study to pinpoint the exact adaptive purposes of these regions. Further research is also required to analyze how blubber thickness, water temperature, and food intake are linked. This study found a correlation whereby food intake decreased with increasing water temperature. The causal links among these three factors require further exploration. For instance, do warmer temperatures reduce food intake, which in turn uses already stored energy, hence reducing blubber thickness? Or do increasing temperatures directly affect blubber thickness, which may suppress appetite? And by what mechanisms do these changes occur?

RELATED: Narwhal tusks expose climate change

The opportunity for further study with these fascinating creatures suggests an exciting future for marine research on the Yangtze River.

The context

The Yangtze River is the longest river in Asia and the third longest river in the world. It is described as the “river of life”—an apt nickname given that it accounts for 40 percent of China’s fresh water and hence supports the lives of millions of people and a diverse range of wildlife.

However, the Yangtze River has long been overused by humans. Industrialized fishing, and illegal overfishing, have seen prey numbers dwindle in the river. Meanwhile, excessive use of container ships, barges, and speedboats have created new physical and chemical dangers.

RELATED: Marine Mammals Need a Voice in the Fishing Industry

Such use has already led to the extinction of the ‘baiji’ or the Yangtze River Dolphin, a species of dolphin unique to the Yangtze River. The baiji was declared functionally extinct in 2002. As such, the Yangtze Finless Porpoise is the last living cetacean unique to the Yangtze River. They are currently deemed critically endangered.

Their predicament is well summarized in an essay by Douglas Adams, in which he said of these cetaceans, “somewhere beneath or around me there were intelligent animals whose perceptive universe we could scarcely begin to imagine, living in a seething, poisoned, deafening world.”

However, the research being undertaken with the YFPs is a positive sign that hopefully the porpoises will not suffer the same fate as the baiji. By understanding the blubber adaptations of the YFPs, scientists can work toward protecting them better in the future.

This study was published in the peer-reviewed journal KeAI – Chinese Roots Global Impact – Water Biology and Security.

References

Adams, D., & Carwardine, M. (1991). Blind Panic. In Last chance to see, 165. London: Pan Books.

Ding, W. (2021). Protecting cetaceans in the Yangtze. The UNESCO Courier. https://en.unesco.org/courier/2021-3/protecting-cetaceans-yangtze

Tang, B., Hao, Y., Wang, C., Deng, Z., Shu, G., Wang, K., & Wang, D. (2023). Variation of blubber thickness of the Yangtze finless porpoise (Neophocaena asiaeorientalis asiaeorientalis) in human care: Adaptation to environmental temperature. Water Biology and Security, 2(4), 100200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watbs.2023.100200

World Wildlife Fund. (2023). Yangtze finless porpoise. https://www.worldwildlife.org/species/yangtze-finless-porpoise

About the Author

Amelia Hersant is an office worker by day but a surfer, traveler, and all around lover of the great outdoors in her spare time. When all is said and done, there is nothing she likes more than stretching out by the sea to read about the adventures of humans and animals alike.