The scent of lavender is loved by humans and insects alike, but what makes lavender scent so attractive? A group of scientists decided to find out.

The relaxing scent of lavender graces all sorts of candles, tea, lotions and potions worldwide. Its ties to stress relief, sleep promotion and skincare have been used for centuries. But now, a team of researchers in China are uncovering what makes lavender so memorable and attractive, for people and insects alike.

Clues from the past

Lavender, known scientifically as Lavandula angustifolia, is native to the Mediterranean but has been introduced to regions across the globe. According to Dr. Lei Shi, a professor at the Chinese Academy of Sciences Institute of Botany, lavender was introduced to China in the 1950s. Despite this relatively recent development, evidence of humans using lavender in fragrances, cooking, gardening and medicine goes back 2,500 years.

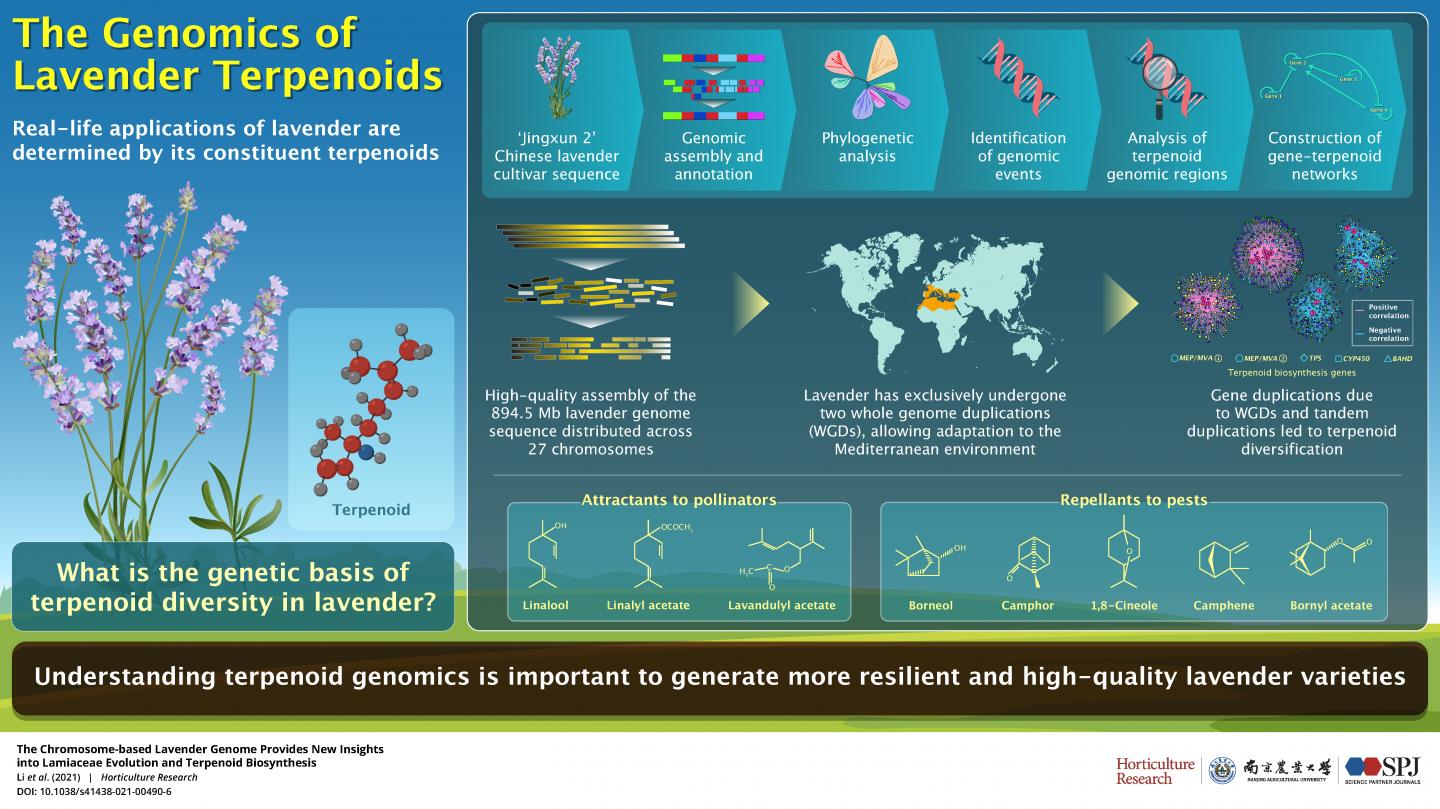

The herb owes its characteristic scent to chemicals called terpenoids, which exude smells to play an important role in a plant’s survival. Terpenoids can either attract pollinators to help spread a species’ genetic material, or deter herbivores that might kill the plant and keep it from reproducing.

To better understand lavender’s terpenoids, Shi and his team pieced together the plant’s entire genome. They assembled a 894.5 Mb genome of the Chinese-developed “Jingxun 2” lavender variety, which allowed them to analyze its entire genetic history, or phylogeny, down to the very chromosomes of which it is assembled.

They took a special interest in the terpenoid-producing genes of the plant, and established networks between the genes in the genome sequence and terpenoids found in lavender, coming to the conclusion that lavender was forced to evolve in response to major ecological events. Its fragrant compounds had to change right along with it.

RELATED: Plant DNA shared through horizontal genome transfer

Aromatic adaptations

According to the study, published in May, it is the first to pinpoint the contents of terpenoids in lavender. For example, sweet, floral-smelling chemicals such as linalool and linalyl acetate made up about 72% of the volatile chemicals in lavender flowers, with the purpose of attracting pollinators. By contrast, few of the sweet, floral-smelling chemicals were found in the stem and leaves. In these parts of the plant, slightly spicy, deterrent smells like camphor were far more prevalent, helping to stave off herbivores that might otherwise eat it.

RELATED: Parasitic Plant Has Edge in Evolutionary Arms Race

Though draft genomes of lavender have been assembled in the past, this study was also the first to explore lavender’s genetic duplications and theorize what might have caused them. Major environmental shifts happened near both of lavender’s major genetic splits. The first one, about 29.6 million years ago, occurred after a mass-extinction event in Europe, which also correlated with a sudden climate cooldown. Near the second genetic split, around 6.9 million years ago, the Mediterranean Sea went through cycles of drying up almost completely–another drastic ecological shift.

RELATED: Genome Revelations: How Green Plants Evolved

Shi and his team think organisms that undergo these kinds of huge shifts in genetic material may be better positioned to adapt to environmental changes, and similar occurrences have been found in other plant families.

“Plants have the capacity to duplicate their genomes and when this happens there is freedom for the duplicated genes to evolve to do other things,” says Shi.

In the case of the “Jingxun 2” cultivar, this genetic split not only helped lavender develop more effective methods of staving off predators and attracting pollinators, but also helped it adapt to colder climates in the Mediterranean.

Protecting lavender’s future

Shi says better varieties of lavender are “urgently needed” and that degradation of cultivated varieties is of concern to those who grow and use lavender. This study not only highlighted new discoveries in lavender’s evolution, but could help create higher-quality varieties of lavender in the future.

This research benefits humans, with the increased knowledge of how to provide better essential oils and additives we humans use in candles, bath bombs and other products, but it could also help protect this precious plant against future disease and climate change, helping it survive major ecological shifts just like its ancestors.

This study was published in the peer-reviewed journal Horticultural Research.

Read more: Genomics Takes on Crop Disease

Reference

Li, J., Wang, Y., Dong, Y. et al. The chromosome-based lavender genome provides new insights into Lamiaceae evolution and terpenoid biosynthesis. Hortic Res 8, 53 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41438-021-00490-6

Featured photo courtesy of Lei Shi.

About the Author

Mackenzie Myers Fowler is a science writer, avid knitter, and former field station ragamuffin. She holds an MFA in nonfiction writing but would be a soil scientist if she could do it all over again. She lives in Michigan with her husband, her cat and a plethora of houseplants.