SciStarter Blog

Situated Citizen Science

In Science By the People, Kimura and Kinchy describe their challenging research subject: understanding how people are impacted by science. Their work illustrates how the complex social systems people have created (and that have changed overtime) shape how science is conducted today.

In the preface to their book, Kimura and Kinchy offer what they call a “genealogy” of their text. This genealogy includes learning about their lives, what led them to write this book, and the scholarly traditions from which they draw. This preface provides a unique insight into how they study citizen science. Kimura also offers a similar genealogy in her book Radiation Brain Moms (2016, Duke UP), which we reviewed back in December.

Challenges for Environmental Citizen Science

“Environmental Citizen Science: Virtues and Dilemmas” is the first chapter of the book. Kimura and Kinchy explain how the term “citizen science” has become an umbrella term for a variety of practices. They also discuss the complexities found within different varieties of citizen science. They identify four broad issues in citizen science: volunteering, taking a stand (activism and related political engagements), contextualizing data, and shifting scales (local or global research).

Kimura and Kinchy raise big questions about the value of citizen science, to what uses it might be put, and what drawbacks it might have. Their questions broadly address how we understand the virtues and vices of citizen science.

This book shares neither the naive enthusiasm for citizen science nor the cynicism that permeates many critiques. As environmental sociologists, we aim to understand how citizen science affects people’s lives and environments.

— Kimura and Kinchy, Science By the People, page 3

“How is Environmental Citizen Science Political?,” chapter 2, details how citizen science efforts can be politically transformative or reinforce exclusionary practices. Kimura and Kinchy cite the example of women’s participation in Japan following the disaster at Fukushima Daiichi. Women faced harsh political criticism when they attempted to discuss food contamination. Citizen science is strengthened when projects consider these kinds of social issues. Who does or does not get included should be considered in project design. Challenges, however, are faced even in those cases that do consider such questions. Further challenges include ensuring strong regulatory frameworks, sufficient public funding for science, policy mechanisms that incorporate citizen science findings, and socially contextualized data. Kimura and Kinchy illustrate how these issues come together in different ways in each citizen science project.

“Investigating the Impacts of Fracking,” chapter 3, is the first of three chapters that offer case studies to explore the virtues and vices facing citizen science. In this chapter, citizen environmental monitoring around fracking is examined. Fracking is a process where natural gas can be extracted by drilling into the earth. Drilling is first done vertically and then horizontally. After that water, sand, and chemicals are injected to free gas in the ground. The process has seen rapid uptake in the US. Kimura and Kinchy explain there are many questions about the environmental impact of this process. Citizen scientists have taken up the task of investigating issues such as water contamination. Citizen scientists face significant challenges in responding to this new and politically-charged process.

“Detecting Radiation,” chapter 4, explores how citizen science projects negotiate scale, politics and activism, volunteering, and contextualizing data following the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster. Kimura and Kinchy explore citizen radiation measuring organizations that helped measure food contamination, the Safecast project that has collected an enormous amount of radiation contamination measurements, and groups measuring ocean water contamination, including the Canadian INFORM project. Such projects position themselves as apolitical. Kimura and Kinchy question what that might mean for advocacy and long-term policy change and risk management.

“Tracking Genetically Engineered Crops,” chapter 5, examines several cases of citizen scientists monitoring the spread of genetically engineered (GE) food crops. Kimura and Kinchy argue that the work these citizen scientists do is more than technical work. Citizen scientists also help addressed larger issues of food security and food justice. Debates about GE foods that only address technical issues misses important questions about the economic impact on farmers or biodiversity in crops and diversity in food options, for example. They also warn us of citizen science projects that seem to be based on the “deficit model” of science communication. The deficit model assumes that publics will agree with experts if those publics just had more technical or scientific knowledge. Communication researchers know that model doesn’t work. Researchers also know that the model ignores important social, cultural, and ethical questions that cannot be answered by technical solutions.

Finally, in “A Vision of Science by and for the People,” Kimura and Kinchy offer insights for how to move forward in citizen science. Their advice could be taken up by scientists, policy-makers and politicians, and citizen scientists. Importantly, their message is one of understanding the complexity of different citizen science efforts and considering them.

An appendix follows the concluding chapter, offering “Resources for Getting Involved in Citizen Science.” Resources are broken down into categories, including professional associations, nonprofits, university-based programs, government resources, academic journals, and television series.

Citizen Science

The issues Kimura and Kinchy raise in their book, including volunteering, taking a stand, contextualizing data, and shifting scales encourage citizen scientists to think critically. Although their book raises difficult issues, these issues are presented in a way that is accessible to many.

Kimura and Kinchy suggest caution about naive optimism in citizen science, but their message is a hopeful one. They write: “By openly acknowledging and grappling with these dilemmas, citizen science can become a more potent force for change” (Kimura & Kinchy, 2019, page 46).

This review is part of an ongoing series of book reviews written by members of Dr. Ashley Rose Mehlenbacher’s research team in partnership with SciStarter. If you have a recommendation for a book to review, please contact SciStarter Editor Caroline Nickerson at CarolineN@SciStarter.org. This work has been partially supported by the Ontario Ministry of Research, Innovation and Science’s Early Researcher Award program; and the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada Insight Grant program. Views expressed are the opinions of the author and not funding agencies.

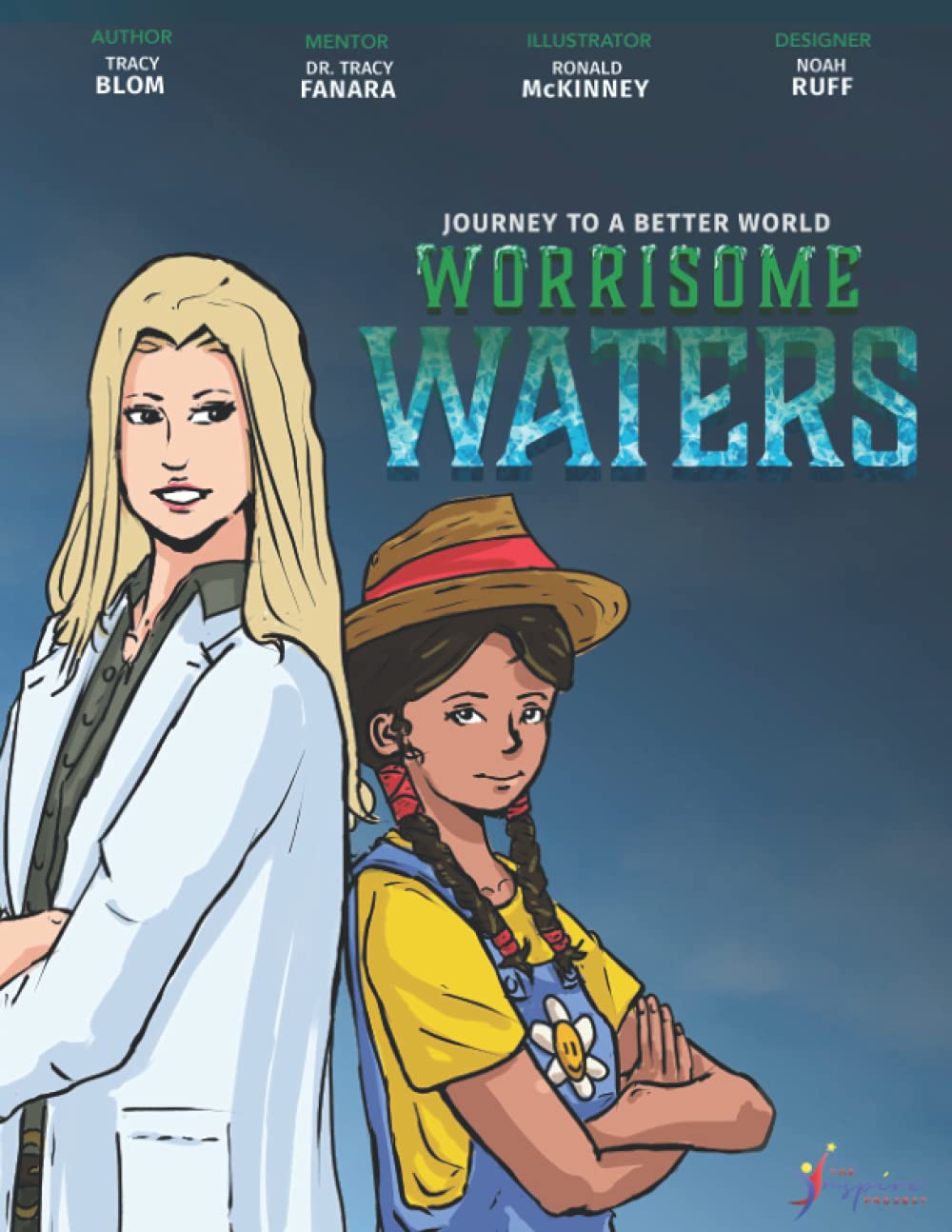

Want more citizen science? Check out SciStarter’s Project Finder! With 3000+ citizen science projects spanning every field of research, task and age group, there’s something for everyone!

About the Author

Dr. Ashley Rose Mehlenbacher is an Assistant Professor in the Department of English Language and Literature at the University of Waterloo, author of Science Communication Online: Engaging Experts and Publics on the Internet(The Ohio State University Press, 2019; open access copy here), and co-editor, with Carolyn R. Miller, of Emerging Genres in New Media Environments (Palgrave, 2017). Mehlenbacher’s research examines science communication, citizen science, and experts and expertise.