The SciStarter Blog

By Eric Betz

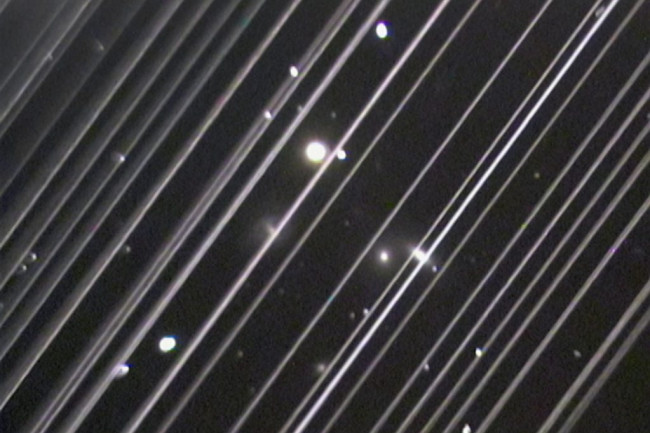

Over the coming years, Elon Musk’s private spaceflight company, SpaceX, will launch thousands of small satellites as part of an effort to provide global, space-based internet. But with each launch, astronomers have grown increasingly worried that this satellite constellation, called Starlink, will interfere with their telescopes’ abilities to study the night sky. This week, scientists with the Russian Academy of Sciences announced that they’ll take their concerns about Starlink to the United Nations, Newsweek reported.

And now educators at NASA have launched a project that asks for the public’s help documenting these satellite streaks as part of a long-term effort to study how the technology will change our night sky. Anyone with a modern smartphone and a tripod can contribute to the Satellite Streak Watcher project.

“People will photograph these Starlink satellite streaks, and we’ll collect a large archive of these over time,” says astronomer Sten Odenwald, Director of Citizen Science for the NASA Space Science Education Consortium. “It’s going to document the degradation of our night sky by these low-Earth orbit satellites.”

Fight Against Light Pollution

Astronomers have been losing the fight against light pollution for decades. Increasingly powerful lights from street lamps, sports complexes, businesses and homes reflect their radiation into the night sky, washing out the stars. Light pollution increases about two percent each year in both areas lit and the brightness of that light, according to a 2017 study. The public is already documenting these changes through citizen science projects that measure light pollution.

But until recently, the attention has typically focused on the ground.

That started to change with the first few launches of Starlink satellites. Astrophotographers and amateur astronomers immediately noticed these spacecraft streaking across the sky. The streaks are particularly prominent just after launch, when the satellites are still bunched together. Some skygazers have compared it to a “string of pearls” drifting across the night sky.

“We could have 5,000 to 10,000 of these satellites buzzing around low-Earth orbit at some point. You could do before and after photos to show how much more annoying the sky is than it used to be.”

Sten Odenwald, Director of Citizen Science for the NASA Space Science Education Consortium

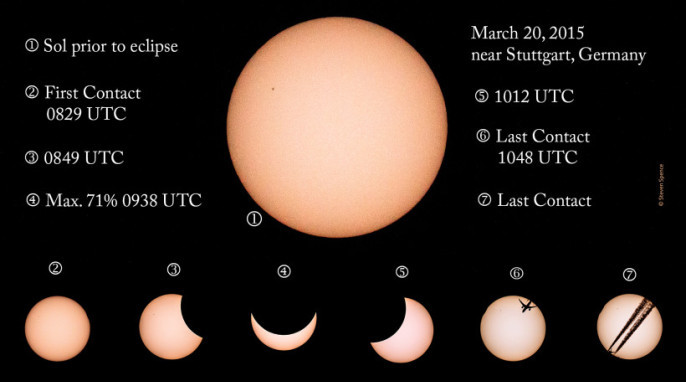

Many satellites are visible from Earth in the hours after sunset and before sunrise, when sunlight reflects off their surfaces and solar panels. The closer a spacecraft is to Earth, the brighter it appears to those looking up.

SpaceX’s satellites stand apart because of their sheer volume and low orbit.

Satellite Internet Constellations

To beam internet connectivity back to Earth, many of these will have a shallow orbit. There also has to be thousands of them to provide global coverage. By the time SpaceX is finished, the company could have as many as 40,000 new spacecraft in orbit. They’ve already announced plans to launch 60 satellites every other week through 2020. For comparison, there are currently just over 2,000 active satellites in orbit right now. SpaceX isn’t the only company with visions of dominating satellite internet, either. A handful of competitors, including Amazon, intend to launch their own constellations.

For its part, SpaceX has started experimenting with low-reflectivity materials to coat the satellites. However, from an engineering perspective, satellites need reflective materials to keep cool.

“The problem is made worse because the satellites are in low-Earth orbit,” Odenwald says. “They’re brighter because they’re lower. And because there are so many of them, it means (astronomers) get maybe as much as an hour of bright streaks going across their sensitive photographic detectors.”

Those numbers are the real worry for scientists. Astronomers have already moved their telescopes to increasingly remote locations to avoid light pollution. But there’s nothing they can do to avoid bright satellites streaking through and ruining their images.

Take Part: Join the Satellite Streak Watcher project.

Cell Phone Astronomy

Odenwald says that inspired him to launch the Satellite Streak Watcher project and ask citizen scientists all over the world to take pictures of these satellites with their cellphones.

To take part, you’ll need a very basic tripod and a reasonably new smartphone. The veteran astronomer says he’s been amazed at the quality of night-sky images now coming from smartphones. Many phones are now sensitive enough to capture the Milky Way, and he’s even seen detailed shots of the International Space Station taken by holding a phone up to a telescope eyepiece.

“If you’ve got a new phone, it’s probably good enough to do this, and several of them have night sky modes, which is perfect,” he adds. Even phones dating back to 2016 or so should be able to photograph these satellites in about four seconds.

You’ll want to master your phone’s long exposure or night sky setting before heading outside. On older iPhones, you can also capture a Live image and set the exposure to 10 seconds. These work differently than traditional DSLR cameras, which leave the shutter open to capture longer exposures, but the end result is very similar.

You’ll also need to know when the satellites are passing overhead. To find out, you can go to Heavens-Above.com and enter your location. The website will give you a list of satellites and the times that they’re passing over your region. Setup your tripod in advance and point it at the region you want to photograph, then wait for the satellite to appear. To upload your images, simply go to the Satellite Streak Watcher project website and include your exposure and the background constellation.

Even astrophotographers with DSLRs are welcome to contribute. They should use a lens wide enough to capture a broad swath of the night sky, but not one that’s so wide it distorts the field. About a 50mm lens should be perfect.

All-Sky Survey

Odenwald says there’s not a clearly defined scientific end goal at the moment. Rather, he’s hoping to document these streaks for a five-year period so that one day, astronomers can tap into the photos and study how satellite streaks have changed over time.

Throughout the history of astronomy, all-sky surveys — traditionally done with much larger telescopes — have proven pivotal to a broad range of research, he points out. And the ways those images proved useful wasn’t always anticipated by the astronomers who gathered them.

“We could have 5,000 to 10,000 of these satellites buzzing around low-Earth orbit at some point,” Odenwald says. If nothing else, “you could do before and after photos to show how much more annoying the sky is than it used to be.”

Find more citizen science projects at SciStarter.org.

Eric Betz is a science and tech writer for Discover Magazine, Astronomy Magazine, and others. He is a lover of #darkskies and pale blue dots.

Featured Photo: Telescopes at Lowell Observatory in Arizona captured this image of galaxies on May 25, their images marred by the reflected light from more than 25 Starlink satellites as they passed overhead. (Credit: Victoria Girgis/Lowell Observatory)