By Helen Cheng (@ms_helenc / @thebiotaproject)

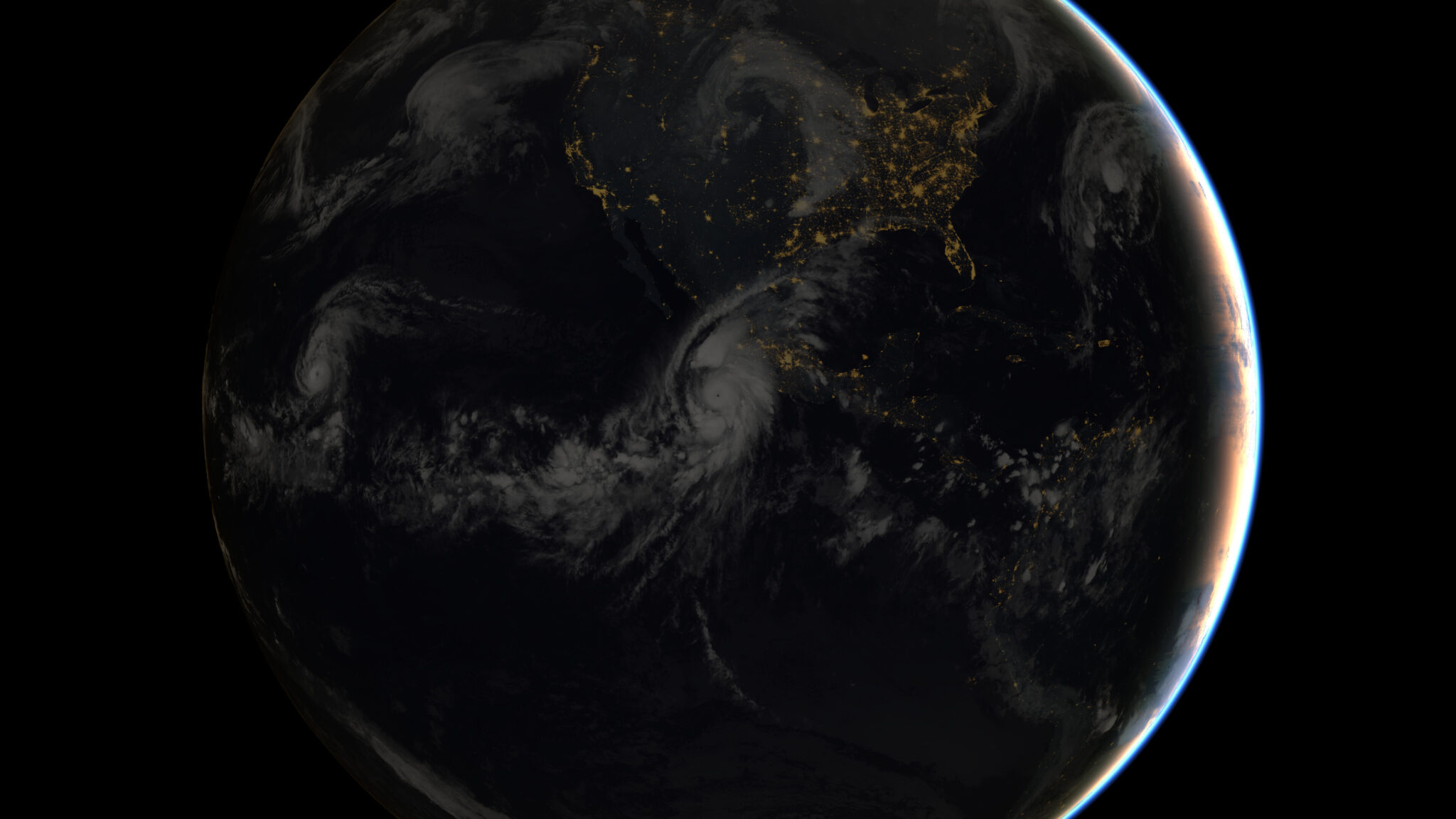

For those who live along the United States East Coast, October is the height of the hurricane season. According to the National Hurricane Center, the Atlantic hurricane season runs from June 1 to November 30. The peak of the season is mid-August to late October, as shown in the graph below, with the number of storms increasing during this time of year. However, deadly hurricanes can occur anytime in the hurricane season. Understanding communities’ past experiences of hurricanes and how they perceive forecasts for such disasters helps build not only preparedness for future storms but also overall community resiliency.

What is a hurricane and what can make it deadly?

A hurricane is a type of storm known as a tropical cyclone, which forms over tropical or subtropical waters. Tropical cyclones have varying wind levels. A tropical cyclone with maximum sustained winds of 39 mph or higher is called a tropical storm. When a storm’s maximum sustained winds reach 74 mph (think of the maximum safest speed of a car on a highway) it is then called a hurricane. The Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale is a rating system based on a hurricane’s maximum sustained winds. The higher the category, the greater the hurricane’s potential to damage property. A category 5 hurricane consists of sustained winds of well over 150 mph—strong enough to blow over an entire framed house. But it is not the winds alone that make hurricanes disastrous; rather it is the water element that causes the most damage and deaths.

Combined power of wind and water

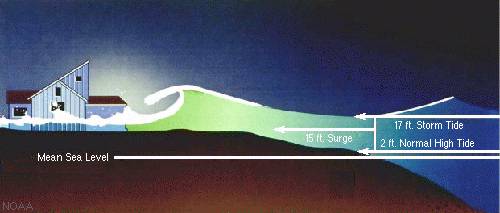

Winds are part of hurricanes’ power, but the combined effect of wind and water make hurricanes a huge threat to communities along the coast. Storm surge is the abnormal rise in sea level during a storm. The surge is caused primarily by a storm’s winds pushing water onshore. Storm surge can reach heights of well over 20 feet and can span hundreds of miles of coastline. The destructive power of storm surge and large battering waves can result in loss of life, destruction of buildings, beach and dune erosion, and road and bridge damage along the coast.

Hurricane impacts on coastal communities

Although we might wish that people impacted by these storms could simply rebuild their homes and easily recover, the situation is much more complex. Even before Hurricane Matthew struck the southeast coast in 2016, more than 100,000 people were already displaced from their homes because of previous storms. Hurricane Matthew was the first category 5 hurricane that had formed and made landfall since 2007. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) reported that the maximum storm surge measured by tide gauges in the United States was 7.70 feet above normal tide levels. This hurricane caused widespread devastation in the southeastern United States and a humanitarian crisis in Haiti. There were as many as 600 fatalities, 34 of which were in the United States.

Communities in the face of a storm

Since storms and the damage they inflict can be so disastrous for so many people, there are efforts to raise awareness and to boost resilience, not only through traditional education and outreach but also by bringing people together to work on preparedness and adaptation for future storms and disasters.

While scientists study storms and hurricanes, other professionals are working with scientists to help translate their knowledge, while bringing coastal communities together to think about the future of climate adaptation. Jill Gambill is the Community Resilience Specialist with the University of Georgia (UGA) Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant. Working in extension, which consists of applying research to provide education and outreach, Gambill focuses on climate communication, public engagement, hazard mitigation, climate adaptation, and climate policy. But most importantly she brings together diverse groups from diverse communities throughout the southeastern United States to plan effectively for storms and the associated flooding and sea level rise.

Georgia was hit with four major hurricanes four years in a row: Matthew (2016), Irma (2017), Michael (2018), and recently Dorian (2019). These hurricanes caused mandatory evacuations; residents were required to leave their homes to go to safe places. After Hurricanes Matthew and Irma, Gambill worked with researchers at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) to bring together members of several communities in the southeastern United States to have candid conversations. She asked people from these communities about their understanding of forecasts, storm surges, climate, and hurricanes. Assessing their knowledge of climate-related information and their decision-making experiences, Gambill started to understand what goes through the minds of community members and the possible misconceptions and confusing communications that they may face.

“One thing we realized is that there is a big misconception about if your house is elevated to a point that you may not experience flooding, people were thinking that meant that they were safe and not understanding that you may lose power, all of the roads around you may be flooded, you may not have drinking water, your wastewater system may not be working, emergency services may not get to you. So just because your house is above a 9-foot storm surge projection, you still need to follow evacuation orders,” Gambill explains (personal communication, September 16, 2019).

While maps can depict the path of a storm and areas that are expected to be impacted, when Gambill and her partners created and displayed GIS visualization projections of storm surge from an “on-the-ground” perspective—demonstrating personal impacts—it was much more effective in providing audiences a scenario of what can happen in real life and how they might feel during a hurricane situation. Modeled on measurements gathered from Hurricane Matthew, these visualizations brought on emotional responses in the focus group members. Watch one of the visualizations here:

Gambill has also been working with science partners at UGA to use virtual-reality technology to create simulation programs about storm surge and its impact on a house in a coastal area, creating a sense of place and the experience of a hurricane. While the disaster is a simulation, there is a “do-over” scenario that uses the same hurricane magnitudes but allow users to customize actions to take in the face of storm surge, such as elevating the house or acquiring flood insurance, while providing a narration of the scenario.

The value of a sense of place is important especially with storm forecasts. Gambill explains that there is a need to understand what kind of information should be included in forecasts to help people make better decisions and to give a sense of place; for example, predicting the impacts of a storm on schools and landmarks. To help understand what tools and information are needed to help people make decisions, there is a need to incorporate the diverse perspectives of communities living in different areas (urban, rural, barrier island) as well as representing different cultures. Gambill’s next steps are to conduct focus groups in communities living on barrier islands, whose members may be more in tune with elements of their environment, such as the timing of tides, as well as rural inland residents who may be less aware of coastal threats. Her purpose with these focus groups is to see different perspectives from different communities.

Throughout these meetings and in planning for disasters prior to the hurricane season, Gambill feels that with traditional methods of communication about disaster planning, “We may be leaving really important perspectives out.” However, in recent years, there has been a shift to try to engage with more diverse audiences and, rather than a “top-down” lecture, the goal is to have a two-way dialogue, identifying opportunities together. She concludes, “In order for more resiliency efforts and safety efforts to be successful and sustainable, you have to have diverse voices at the table.”

Enjoy more articles like this one on the Biota Project Blog.

—Helen Cheng currently works on coastal resilience issues in New York City. She previously worked in Washington, DC, on United States marine policy and resiliency. Helen received her MS degree from the University of New Hampshire, studying the population dynamics and behavior of American horseshoe crabs (Limulus polyphemus). Helen works on a variety of projects involving research, education and outreach, and science communication. In her free time, she enjoys hiking in the mountains and rock climbing.

References

NCAR & UCAR Education and Outreach (2017, September 8). Storm surge visualization. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6W_20bwqWo

NOAA National Hurricane Center (2017). National Hurricane Center Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Matthew. Retrieved from https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/tcr/AL142016_Matthew.pdf