A team of paleontologists reveals new details about one of the most striking transformations in evolutionary history: a toothed bird.

By Kate Stone

Sometimes what you seek is right under your nose. Using fossils found in the 1870s, paleontologists have pieced together the skull of a toothed bird that represents a pivotal moment in the transition from dinosaurs to modern birds.

“Right under our noses this whole time was an amazing, transitional bird.”

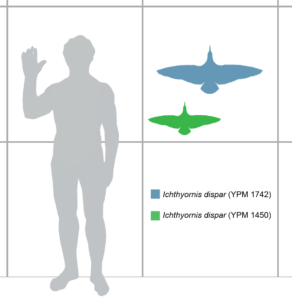

Ichthyornis dispar is a key member of the evolutionary lineage that leads from dinosaurian species to today’s birds. It lived nearly 100 million years ago in North America and looked like a toothy seabird—like a gull or a tern with teeth. The fossil found in 1873 was named and described by Othniel Charles Marsh after some initial confusion about what sort of animal it was. In fact, Marsh at first thought the fossil contained two animals: the body of a bird and the head of a small aquatic reptile. This shows why uncertainty, testing hypotheses, and re-examining evidence are all important parts of scientific research.

“The story of the evolution of birds, the most species-rich group of vertebrates on land, is one of the most important in all of history. It is, after all, still the Age of Dinosaurs.”

Partial specimens of Ichthyornis dispar have been unearthed in subsequent years, but there has been no significant new skull material of this toothed bird since those first fragmentary remains found in the 1870s. Now, a team of paleontologists reports on new specimens with three-dimensional cranial remains—including some that have been on a shelf at Yale since the 1870s—that reveal new details about one of the most striking transformations in evolutionary history.

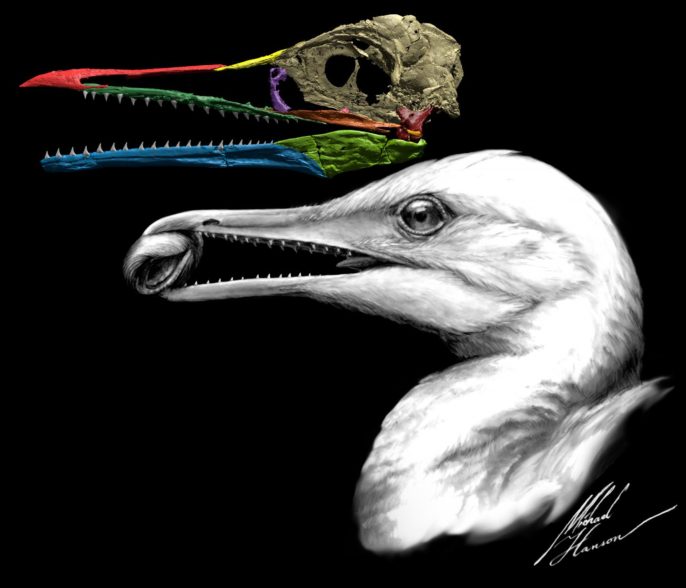

“Right under our noses this whole time was an amazing, transitional bird,” says paleontologist Bhart-Anjan Bhullar. “It has a modern-looking brain along with a remarkably dinosaurian jaw muscle configuration.”

Related: Prehistoric Crocodiles Ruled Ancient Peru

Looking a toothed bird in the mouth

Perhaps most interesting of all is that Ichthyornis dispar shows us what the bird beak looked like as it first appeared in nature.

“The first beak was a horn-covered pincer tip at the end of the jaw,” says Bhullar, who is an assistant professor and assistant curator in geology and geophysics. “The remainder of the jaw was filled with teeth. At its origin, the beak was a precision grasping mechanism that served as a surrogate hand as the hands transformed into wings.”

“The fossil record provides our only direct evidence of the evolutionary transformations that have given rise to modern forms,” adds Daniel Field of the Milner Centre for Evolution at the University of Bath. “This extraordinary new specimen reveals the surprisingly late retention of dinosaur-like features in the skull of Ichthyornis—one of the closest-known relatives of modern birds from the Age of Reptiles.”

From toothed bird to toothless

The researchers say their findings offer new insight into how the skulls of modern birds eventually formed as toothed birds lost their teeth. Along with its transitional beak, Ichthyornis dispar had a brain similar to modern birds but a temporal region of the skull that was strikingly like that of a dinosaur—indicating that during the evolution of birds, the brain transformed first while the remainder of the skull remained more primitive and dinosaur-like. Paleontologists can add this new knowledge of bird beaks to other discoveries about early bird bodies, such as feathers preserved in amber and on fossils of Archaeopteryx.

“Ichthyornis would have looked very similar to today’s seabirds, probably very much like a gull or tern,” says Michael Hanson of Yale University. “The teeth probably would not have been visible unless the mouth was open.”

“The story of the evolution of birds, the most species-rich group of vertebrates on land, is one of the most important in all of history. It is, after all, still the Age of Dinosaurs,” says Bhullar.

The research team conducted its analysis using CT scan technology, combined with specimens from the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History; the Sternberg Museum of Natural History in Fort Hays, Kansas; the Alabama Museum of Natural History; the University of Kansas Biodiversity Institute; and the Black Hills Institute of Geological Research.

This research is published in the journal Nature. The research was supported, in part, by Yale University; the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History; the University of Bath; the Alexander Wetmore Memorial Research Award; the Stephen J. Gould Award; and grants from the National Science Foundation, the Yale Institute for Biospheric Studies, the Evolving Earth Foundation, and the Frank M. Chapman Memorial Fund.

Featured image: Fossil reconstruction and illustration of Ichthyornis dispar. Credit Michael Hanson/Yale University.

Reference

Field, D. J., Hanson, M., Burnham, D., Wilson, L. E., Super, K., Ehret, D., . . . Bhullar, B. S. (2018). Complete Ichthyornis skull illuminates mosaic assembly of the avian head. Nature, 557(7703), 96-100. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0053-y