The ancient teeth of a human ancestor are unlike anything ever found in Europe or Asia and will force us to reexamine the theory that humans originated from Africa.

Teeth fossils were discovered near the German town Eppelsheim in a former riverbed of the Rhine. Due to sheer confusion, researchers held off on publishing their research for the past year—that is, until they released a preprint detailing the teeth today. We spoke with the study’s lead author, Herbert Lutz, to find out more about the work.

ResearchGate: What’s so exciting about this find?

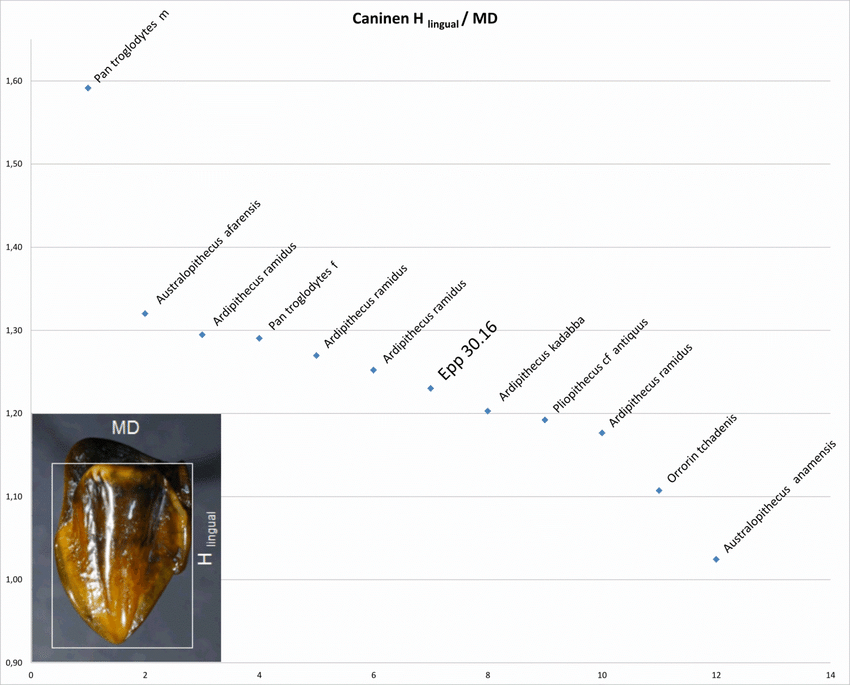

Lutz: The fossils we’ve found aren’t what we’d expect for the area we found them in. We don’t know where this new species fits in the family tree. There are similarities to species that lived in Europe around this time, but one tooth, the canine, differs from these. We know of similar examples from Africa, but these new finds are considerably older. We don’t want to speculate, but we wonder what could explain that. That investigation is just starting.

RELATED: Oldest Primates Lived in Trees

RG: What other types of primates existed in Europe at that time, and how does your find of these ancient teeth fit into the picture?

Lutz: In the Miocene—we’re talking about a window of time more or less 10 million years before present—there were multiple primate species in Europe, but they mostly lived near the Mediterranean. My colleagues in Spain, Italy, Turkey, and Hungary have plenty of archaeological material from this time. But once you get north of the Alps, the fossil situation is very, very sparse. This region, Eppelsheim in Rhenish Hesse, is the northernmost site for deposits from this time period in existence. Over the last 200 years, around 10 primate species were found there; almost all of these finds were lost in the Second World War. This is not only the first time something like this has been found here in over 80 years, but it’s something completely new, something previously unknown to science.

RELATED: Bipedal Movement by Ancestors Reconfirmed in 3D Models

RG: Can you say already what this find will mean for our understanding of human history?

Lutz: We want to hold back on speculation. What these finds definitely show us is that the holes in our knowledge and in the fossil record are much bigger than previously thought. So we’ve got the puzzle of having finds that, in terms of the expected timeline, don’t fit the region we found them in. We’ve got two teeth from a single individual; that means there must have been a whole population. It wouldn’t have been just one, all alone like Robinson Crusoe. So the question is, if we’re finding primate species all around the Mediterranean area, why not any like this? It’s a complete mystery where this individual came from, and why nobody’s ever found a tooth like this somewhere before.

RG: Do you have any ideas as to how this could happen?

Lutz: It’s possible that, with the morphology of this canine tooth being so similar to more recent examples from Africa, the species could be related. That would mean that a group of primates was in Europe before it was in Africa.

There’s also the phenomenon of convergence, when evolutionary pressure causes the same characteristic to develop in multiple locations. Now the question is whether it’s possible that’s what happened. There are a few thousand kilometers between the species in east Africa and here in central Europe, and millions of years. Is it possible that this uncannily similar characteristic developed two times, completely independently of one another? So here we are, perplexed by these ancient teeth. We want to collaborate with other researchers to process these finds, and hopefully in one or two years, we’ll know a lot more about what we’ve got on our hands. It’s definitely a fantastic, exciting story.

RG: What are the next steps?

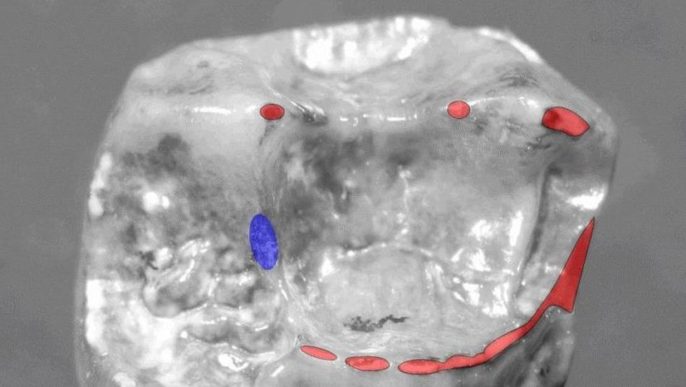

Lutz: We’ll get in touch with our colleagues, who are just as surprised and dumbfounded as we are right now. We want to bring in specialists in particular investigative methods. The preservation of the crown of the tooth and its enamel is absolutely outstanding. These ancient teeth are as well preserved as if I’d ripped them out yesterday, so we can use high-resolution x-rays to examine the inner structure of the enamel; that can give you information about the individual’s age and the development of this particular animal—things like stunted growth. It’s similar to tree rings. Another colleague of mine is focusing on wear on the chewing surface. There are tiny scratches and indentations, and there are areas where the tooth is chewed up. From all of this, you can draw conclusions about diet. These are all investigations that can be done really well with these samples, but we’re just getting started with all that.

RELATED: Want to Be a Forensic Anthropologist?

Translated from German. Featured image courtesy of Herbert Lutz.

A version of this article was originally published by our friends at ResearchGate.

Featured image: Molar Epp 13.16 in occlusal view showing in red the first traces of macrowear. Damages most likely caused by biting on mineral (quartz) grains are highlighted in blue.