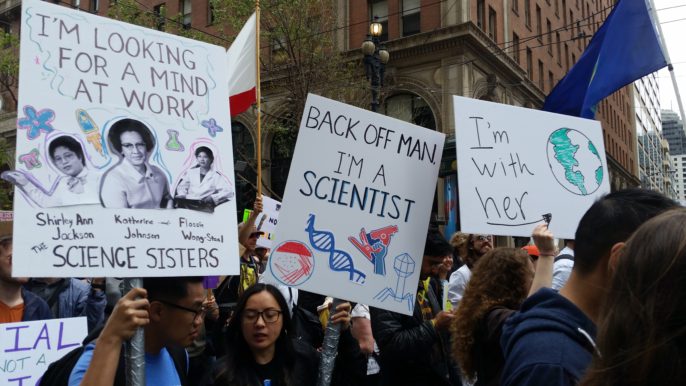

Science journalist Shayna Keyles joined the March for Science in San Francisco and interviewed many other marchers. Find out what brought them all together.

Tens of thousands descended on state and country capitals on Earth Day to march for science, and I was one of them. I joined up with fellow science lovers in San Francisco, where carbon-based comrades waved permanent-marker protest signs at each other in acknowledgment and wore T-shirts emblazoned with puns or allegiances to research organizations and educational associations. Some even wore lab coats, and one man was spotted wearing a spacesuit and helmet from NASA.

People all had their own reasons for marching, but one of the most common motivators was a denunciation of “alternative facts.” This was true for Dan Jackson, a lab researcher at an environmental lab in Berkeley, who told me that he felt legislators find the facts of science inconvenient, so they make things up to combat evidence of climate change and sea level rise. Jackson wants truth and facts; for him and many others, science represents those things.

He’s not alone in this sentiment. Newspaper subscriptions have surged in the few months since the election, demonstrating that people are looking for credible information, and sites such as Politifact devote time and resources to checking the accuracy of political statements. However, research indicates that despite a public desire for integrity and honesty, regularly shown “fake news” can have the troubling effect of normalizing lies and misinformation. Additionally, many have lost faith in expertise. So even though something might be objectively true, those who propagate and accept “fake news” might reject it.

Fortunately, much of the public does care about facts. Part of the ideology of this march was that science is a field based on fact, and marching for science is thus marching for truth and integrity. Others also marched for conservation, climate protection, environmental regulation, education reform, workplace equality, reproductive rights, and countless other crucial issues—all of which overlap with science.

And while it’s true that there’s a lot of uncertainty in science, that’s no reason to mistrust the entire discipline—that’s a reason to embrace it. Science doesn’t take things on face value, and science doesn’t trust a statement just because of who said it. It’s procedural and precise, it breaks boundaries and tests patience, and that’s what we love about it.

Calling for regulation

It was tough to walk through the throngs of excited scientists, academics, artists, teachers, parents, students, and onlookers that buzzed up and down Market Street, not just because it was so absurdly crowded, but also because it was hard not to stop and marvel at some of the clever and powerful messages people carried with them.

“Teach science, not superstition, in school.”

“Defend science to protect free speech.”

“We are the crew of Spaceship Earth.”

“The ocean is rising, and so are we.”

Before the march began, participants gravitated toward the loudspeakers at Justin Herman Plaza, where Kathy Seitan, a retired EPA project manager, spoke to us about how science and government can—and should—get along. “Economic growth and environmental regulation can exist at the same time,” she proclaimed. She cited the example of the Charles River in Boston: once a source of economic prosperity in Boston and the site of many manufacturing plants, the river became so polluted that to fall in would put a person at risk for toxicity. The river flowed pink and orange in some areas, dead fish floating belly-up along the oil-slicked currents. Local efforts to clean up the river launched in the 1960s, and in 1995, the EPA joined the cleanup, helping make the river swimmable by 2005.

The EPA was created in December 1970, just a few months after the first Earth Day, during which people expressed concern over a different polluted body of water: the Cleveland River caught fire numerous times because of all the chemicals in the water. To its credit, the EPA has continued to monitor both sites, which now permit local recreational activities, house dozens of businesses, and sport vibrant riverside communities.

Role of the people

Unfortunately, the EPA under Scott Pruitt likely won’t be as proactive as it was when Seitan worked there. On the table are threats to back out of the Paris climate accords, fire 25 percent of the EPA’s employees, cut 56 specific protection programs, and reduce funding for alternative energy sources. Private companies, nonprofits, and citizen science operatives are going to have to pick up the government’s slack.

One of those nonprofits is Cool Effect, which features climate scientists who scour the globe seeking out ways to reduce harmful greenhouse gas emissions on a local level. When I talked with some of the group’s representatives at the march, they told me about two such projects in which they’re involved.

In Bagepalli, India, communities make poo productive and reduce methane emissions by installing biogas digesters in their homes. As a result of these installations, less wood is used for energy, more waste is removed in a hygienic manner, and carbon pollution and respiratory illnesses are reduced. Plus, the local economy is stimulated by the creation of biodigesters.

Cool Effect also works with the Ute Tribe in Southern Colorado to reduce up to 60,000 tons of emissions annually by harnessing the power methane steam from the ground and channeling it into existing gas pipelines. How significant is this reduction? From their website, “That’s the equivalent of 3,529 average Americans emitting no greenhouse gases (not even by breathing) for a whole year. Amazing, right?”

Another group making important contributions both locally and globally is Reef Check Worldwide. They have teams in more than 90 countries dedicated to studying climate change and its impact on the oceans, protecting and restoring underwater ecosystems, and collecting and sharing data with other scientists to improve ocean education.

The California branch of Reef Check Worldwide has been operational for over two decades. With stations in Marina del Rey, Monterey, and Fort Bragg, the group has redoubled its efforts to monitor coastal reefs since the passage of the Marine Life Protection Act (MLPA) in 1999. The MLPA protects about 15 percent of all coastal marine areas, but no watch groups were created as an extension of the act, and the EPA did not set aside any funds to ensure the effectiveness of the act. Reef Check Worldwide understands that monitoring these areas is incredibly important: fisheries, canneries, and importers all rely on information about coastal populations, water levels, and foliage, and climatologists and environmentalists rely on data about various population changes. Moreover, a healthy reef ecosystem contributes to a healthy ocean ecosystem. The kelp beds of California’s rocky reefs provide minerals and nutrients to the surrounding area and support a rich diversity of life.

In California alone, Reef Check’s experienced cold-water divers and citizen scientists perform over 70 surveys per year. They have created a statewide database of protected marine areas and partnered with other state agencies to establish ecological baselines for endangered areas and species. Their methods have seen some great successes in conservation. Over the past few years, their surveyors discovered that 95 percent of the abalone population in Northern California has been depleted. Their data was accessible to other agencies and easily confirmed, so fishing and wildlife regulations were changed to protect this large mollusk.

Marching for employment

Many people at the march were attending because of concerns about employment. Hanan Dabwan of San Pablo is a college student who already knows that she wants to do lab research but fears that this administration could severely jeopardize job opportunities for students like her by cutting funding. Joan Damero, an environmental scientist at the Field Museum in Chicago, also worries that reduced funding for the sciences could affect her personal well-being. “There are people working hard to promote knowledge, and taking away funding is taking away their livelihoods.”

Fortunately, groups such as the Association for Women in Science (AWIS) exist to help graduate students and professional scientists retain employment, even in the face of funding challenges. The group nationally advocates for scientists (women and men) in all fields and offers mentoring, professional development, and networking opportunities. In addition, AWIS hosts youth science fairs and spearheads a mentoring program designed to introduce middle school girls to STEM options at an early age.

Traditionally, the sciences have been seen as male-dominated disciplines. Even today, women in STEM currently earn about one-third less than their male counterparts do and often face workplace discrimination. This is one of the reasons AWIS and similar groups exist; it’s tough to be a female scientist, even in this day and age. Just take a look at the Twitter account Women In Science (@WomenScience) or the hashtag #ActualLivingScientist and you’ll see plenty of examples.

“It’s important for young girls to have role models in these careers,” said Shirley Johnson, the AWIS President of San Francisco. “This gives them an opportunity to have a positive experience with science.”

After the march

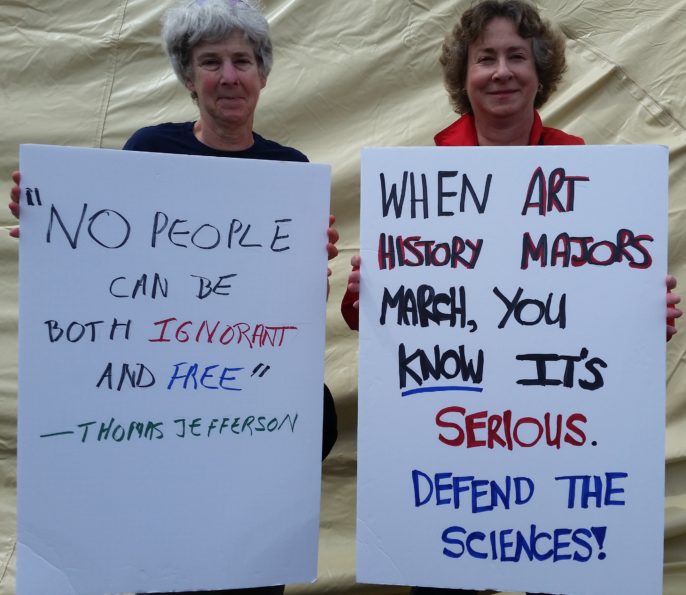

Of course, we all have positive experiences with science every day, regardless of our field of employment. Neither of the women pictured below work in the sciences, but both were attending the march because of the impact science had made on their lives. “I understand that my life would not be the same without science,” said Mary Barnsdale of Berkeley. “Without science, I wouldn’t be vaccinated, wouldn’t have access to the wonderful medical care I receive from Kaiser Permanente, wouldn’t have gas for my car or energy to power the lights in my house … I would have nothing. Every major accomplishment can be marked by science.”

It might sound dramatic, but if you think about it, she might have undersold it a bit. I think it’s fair to say that 90 percent of what we do includes science in some way. This computer I’m typing on, that screen you’re reading on—any innovation you’ve heard of, or haven’t heard of yet, has been touched by science.

As for why I marched? Well, I’ve got a lot on the line, including the air I breathe, the water I drink, and the food I eat. Without biologists to help engineer seeds that can withstand flood, drought, and rot, without chemists to test and monitor the soil and water basins, without air quality control and filtration, we wouldn’t have the basic tools for survival in this industrialized world. And what about that industrialized world? What about the cars we drive, which are improved upon—made safer, faster, more comfortable—on an increasingly regular basis, for increasingly lowering costs? What about the new entertainment, investment, or fitness apps that you use every day? Your medicine or your dental retainer or your hip replacement? What about everything that makes your life easier, or healthier, or happier?

In a world where facts are sometimes disregarded, where science loses funding and is thrown to the wayside, we risk losing the safe food, water, and air that keeps us alive. We risk watching the US GDP plummet as our production stalls, and seeing our quality of life drop as we lose access to life-saving products. And we risk losing out on the rich diversity of local ecosystems, which keep the planet beautiful and abundant.

That’s why I marched, and that’s why I’m a science communicator: because to ensure science is funded, practiced, and productive, it must be made accessible and understandable to all. I’m doing my part by writing about science, from research results to citizen science initiatives to learning options.

Now, you do your part, whatever that may be. If you went to a march, that’s fantastic; think of what your next step will be. If you didn’t march, that’s OK too; you can still contribute. Read or write about your favorite science subject. Hit the lab or call your legislator. Join a citizen science initiative. Enjoy the public park, and help keep it clean. If you have the money available, donate to an organization that you believe in. Show the world that science is for everyone, in every way.

Featured image: From California to New Jersey and points in between, people showed support for science in their I “heart” Science T-shirts from Science Connected. Photos contributed.