Much like in Fight Club, “Where Is My Mind?” is a fitting theme song for zebrafish: after 24 hours they cannot remember if they won or lost.

By Amanda Alvarez

The two opponents circle each other, showing off their scaly might and impressive stripes. Suddenly one darts forward, biting the other near the dorsal fin—and the fish fight is in full swing. The biting and dodging can go on for up to 20 minutes, but this is not a fight to the death. Zebrafish fight to maintain a social hierarchy, and eventually one will concede and withdraw to the bottom of the tank while the victorious opponent circles above.

These winner and loser behaviors, it turns out, are all in their minds, and zebrafish can be turned into winners or losers by tweaking specific brain circuits. According to a new study published in Science, a part of the zebrafish brain called the habenula has two competing neural pathways whose signals are tied to either a winning or losing outcome. Researchers turned off either pathway by genetically engineering fish. Zebrafish with silenced “winning” circuits tended to lose their fights, while fish with impaired “losing” circuits were more likely to win.

RELATED: HARLEQUIN FILEFISH USES SMELL TO FOOL PREDATORS

Zebrafish Brains

The researchers behind this study were actually interested in whether the habenula and nearby brain areas are involved in fight-or-flight behaviors. They had previously found that the ventral or lower part of the habenula helps zebrafish avoid danger by storing information about negative outcomes, such as getting a shock whenever a red light turns on. The ventral habenula, it turns out, is also important for making sure losers behave like losers; more on that below.

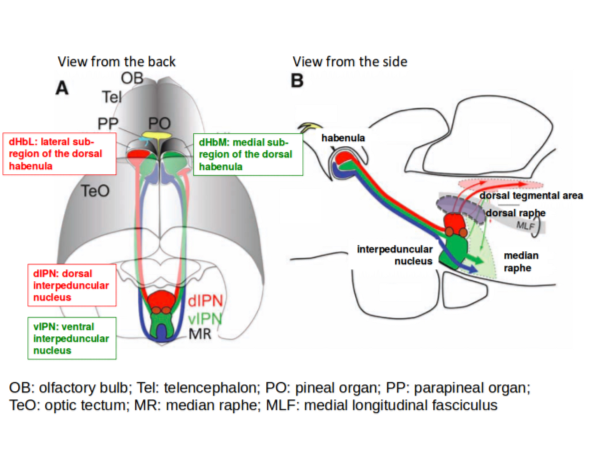

The focus of this new study was the dorsal, or upper, habenula. When researchers measured brain cell activity levels in the dorsal habenula, they found that losing was associated with reduced neural signaling from one subregion, the lateral part of the dorsal habenula.

Taking the experiment a step further, they looked at fighting behaviors in genetically engineered fish with this subregion knocked out. These fish were very likely to lose fights. On the other hand, turning off the opposite subregion, the central part of the dorsal habenula, predisposed fish to win their fights. The neural activity in these two opposing subregions thus seems decisive to fight outcomes.

RELATED: BLUEFIN KILLIFISH FLAMBOYANT FIN COLORS

Moreover, these signals do not stop when the fight is over. Without the usual neural signals from the ventral habenula to a nearby area called the raphe nucleus, loser fish do not withdraw, prompting further attacks from opponents. This first video shows how a losing fish normally behaves, skulking at the bottom of the tank. In the second video, a fish with reduced ventral habenular signaling just cannot stay away from the center of the tank and keeps getting attacked. Acting like a loser is an important component of repelling continued aggression, and for this the ventral habenula is essential.

On the face of it, losing may seem hardwired into the habenula, at least for the genetically altered fish. Actually, according to research group leader Hitoshi Okamoto of the RIKEN Brain Science Institute, what is at play is regulation of a continuum of fleeing, freezing, and fighting behaviors. By producing transgenic fish with different deactivated brain circuits, Okamoto and colleagues observed fish that behaved more aggressively and tenaciously like winners, or were quicker to give up like losers. It is the interplay between these circuits—the strength of the winning or losing signals and the associated rewards and harms for continued aggression or surrender—that eventually steers the behavior of these fish. And much like in Fight Club, “Where Is My Mind?” is a fitting theme song for zebrafish: after 24 hours they cannot remember if they were winners or losers.

—Amanda Alvarez is a science writer living in Japan. She received her PhD from the University of California, Berkeley. Connect with her @neuroamanda.

A version of this article originally appeared on Neurographic.

Featured image: Tohru Murakami. CC BY-NC 2.0.

Reference

Chou MY, Amo R, Kinoshita M, Cherng BW, Shimazaki H, Agetsuma M, Shiraki T, Aoki T, Takahoko M, Yamazaki M, Higashijima S, Okamoto H (2016). Social conflict resolution regulated by two dorsal habenular subregions in zebrafish. Science, 352(6281), 87–90. DOI: 10.1126/science.aac9508