By Neha Jain

@lifesciexplore

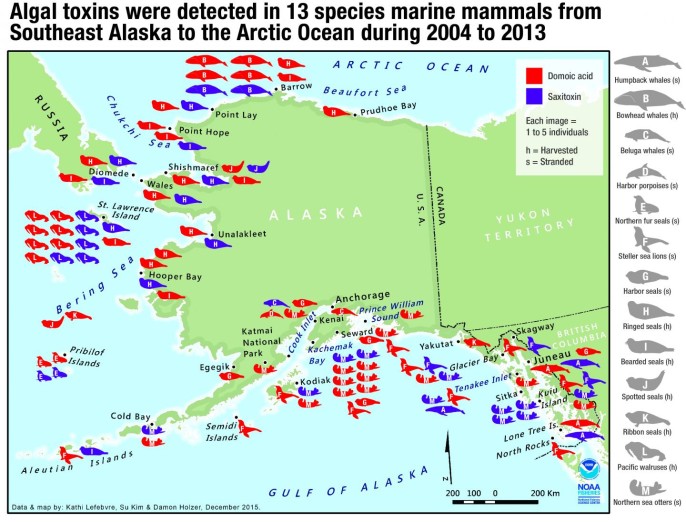

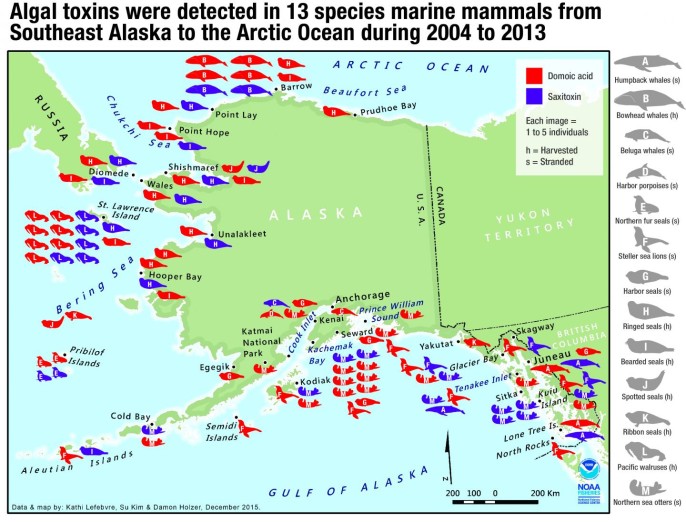

Harmful algal blooms produce toxins that can be deadly to marine mammals. In the US, such toxins—unheard of 20 years ago—have caused almost half of all unusual marine mammal deaths in the last two decades, particularly among California sea lions. Now, for the first time scientists have discovered algal toxins farther north in Alaskan marine mammals; the mammals’ health can be jeopardized by these toxins.

“What really surprised us was finding these toxins so widespread in Alaska, far north of where they have been previously documented in marine mammals,” said Kathi Lefebvre, a scientist at NOAA Fisheries and lead researcher of the study.

Algal blooms occur when some species of phytoplankton grow rapidly while conditions are favorable. They are a common phenomenon in tropical and temperate regions. When populations of certain algae reach particularly high levels, the blooms are clearly visible as green, yellow, red, or brown swirls blanketing the water—sometimes large enough to be seen from space. Some species of phytoplankton produce harmful toxins that have been linked to outbreaks, the most well-known being the first marine mammal poisoning occurrence in 1998, in which 400 California sea lions were stranded and died along the central California coast.

Journey of Toxic Algae

Warming ocean temperatures and record-low sea ice levels in the Arctic have opened up the area to more industrial shipping traffic. Ships can transport harmful algae to the Arctic oceans via ballast water discharge, a mechanism in which ships pick up water from one area and release it in another distant location—sometimes thousands of kilometers away. This process is not regulated in the Arctic and can introduce nonnative species into new areas.

Once deposited, algal toxins can accumulate in tiny filter-feeding zooplankton, invertebrates, and finfish. These are consumed by other fish, and the toxins can accumulate by traveling up the food web to larger marine mammals, as well as to humans.

Two neurotoxins present in harmful algal blooms are domoic acid and saxitoxin. Domoic acid is produced by a type of phytoplankton known as diatoms and causes amnesic shellfish poisoning in humans. In marine mammals, it can cause symptoms such as head weaving or seizures—and even death. The toxin was responsible for the deaths of the California sea lions in 1998, and it has been shown to cross the placenta and to be present in milk. Saxitoxin is a highly potent toxin produced by certain species of dinoflagellates that can paralyze the respiratory system by blocking sodium channels, preventing the propagation of nerve impulses. Scientists do not know much about the effects of saxitoxin in marine mammals.

In 1998, Lefebvre was a graduate student studying domoic acid when news emerged of sea lions stranding themselves on the beaches of California. “Nobody knew why the hundreds of animals were coming onshore and having seizures,” she recalls. She was curious: “I thought it was domoic acid poisoning, so I got samples from the animals and looked for the toxin. We found domoic acid in the feces of the sick sea lions.”

A decade later, Lefebvre decided to find out if these toxins are also present in Alaskan marine mammals. Between 2009 and 2013, Lefebvre and her team collected and analyzed samples (feces, urine, serum, stomach, and intestinal contents) from 905 marine mammals in Alaska that had been stranded, harvested for consumption by locals, or captured for research. The samples came from 13 species including whales, porpoises, seals, sea lions, walruses, and sea otters. The diets of these species are varied and comprise zooplankton, small invertebrates, and finfish.

Widespread Presence

The researchers found that both toxins were present throughout the Alaskan waters. Domoic acid was detected in all 13 species and saxitoxin in 10 of the 13 species. “This shows that algal toxins are present in northern food webs at high enough levels to be detected in marine mammals,” says Lefebvre.

Domoic acid was detected in two-thirds of the bowhead whales and harbor seals tested. Saxitoxin was present in half of the humpback whales and one-third of the bowhead whales. Both of the toxins were present in 46 individuals; the risks of combined exposure are unknown. The high occurrence of both toxins in fecal samples of bowhead whales may be explained by their diet; they forage on zooplankton, which in turn feed on phytoplankton.

The team also discovered three fetuses—one beluga whale, one harbor porpoise, and one Stellar sea lion—in which domoic acid was found, consistent with earlier studies showing the transfer of toxins from pregnant mothers to offspring via the placenta and amniotic fluid.

The domoic acid concentrations in bowhead whales, Pacific walruses, sea otters, and ringed, bearded, and spotted seals are similar to those seen in California sea lions displaying symptoms of seizures.

Since the goal of the study was to mainly detect algal toxin levels, behavioral effects on the marine mammals were not observed since all the samples came from dead animals. “It’s difficult to confirm the cause of death of stranded animals,” says Lefebvre.

The toxins could potentially make larger whales more vulnerable to ship strikes. But it would be difficult to detect this relationship, she says, because of increased ship traffic as well as changes in ice cover in the region. Lefebvre predicts that with rising water temperatures and shrinking sea ice allowing more light penetration, these blooms are likely to expand, “making it more likely that marine mammals could be affected in the future.”

Many of the species sampled are harvested and consumed by Alaskans. Lefebvre and her team have already begun analyzing toxin levels in bowhead whales that have been caught by locals for consumption. “Our goal is to see if we can see a trend of increasing toxin risk over time or a relationship between some environmental factors. If we find a driver that is responsible or related to toxin levels, we could make predictions on what future years may hold for toxins in the food web and risks to marine mammals,” says Lefebvre.

These findings were published in the journal Harmful Algae.

GotScience.org translates complex research findings into accessible insights on science, nature, and technology. Help keep GotScience free! Donate or visit our gift shop. For more science news subscribe to our weekly digest.