By Kate Stone

Comet Lovejoy recently released large amounts of alcohol and sugar into space, according to new observations by an international team. This is the first time we have found ethyl alcohol, the same type in alcoholic beverages, in a comet. The finding adds to the evidence that comets could have been a source of the complex organic molecules necessary for the emergence of life.

Cocktails in Space

“We found that comet Lovejoy was releasing as much alcohol as in at least 500 bottles of wine every second during its peak activity,” explains Nicolas Biver of the Paris Observatory, France. The team watched as the comet released gases containing 21 different organic molecules, including ethyl alcohol and glycolaldehyde, which is a simple sugar.

Comets are understood to be frozen remnants from the formation of our solar system. As such, comets hold enticing clues to how the solar system came to be. Most comets orbit in frigid zones far from the sun. Occasionally, however, a comet passes closer to the sun, where it heats up and releases gases, allowing scientists to see what it is made of.

Comet Lovejoy

Comet Lovejoy (officially cataloged as C/2014 Q2) is one of the brightest and most active comets since Hale-Bopp in 1997. Lovejoy passed closest to the sun on January 30, 2015, releasing liquids at the rate of 20 tons per second. Using a large telescope at Pico Veleta in Spain, the scientists observed a microwave glow emitting from the comet.

Sunlight energizes molecules in the comet’s atmosphere, causing them to glow at specific microwave frequencies. Each kind of molecule glows at a certain frequency, allowing scientists to identify it with detectors on the telescope.

Comets May Have Given Life on Earth a Head Start

Some researchers think that comet impacts on ancient Earth (and possibly on Mars) delivered a supply of organic molecules that could have assisted the origin of life on our planet. Discovery of complex organic molecules in Lovejoy and other comets gives support to this hypothesis.

“The result definitely promotes the idea that comets carry very complex chemistry,” says Stefanie Milam of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “During the Late Heavy Bombardment about 3.8 billion years ago, when many comets and asteroids were blasting into Earth and we were getting our first oceans, life didn’t have to start with just simple molecules like water, carbon monoxide, and nitrogen. Instead, life had something that was much more sophisticated on a molecular level. We’re finding molecules with multiple carbon atoms. So now you can see where sugars start forming, as well as more complex organics such as amino acids—the building blocks of proteins—or nucleobases, the building blocks of DNA. These can start forming much easier than beginning with molecules with only two or three atoms.”

In July, the European Space Agency reported that the Philae lander from its Rosetta spacecraft in orbit around comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko detected 16 organic compounds as it descended toward and then bounced across the comet’s surface. According to the agency, some of those compounds play key roles in the creation of amino acids, nucleobases, and sugars from simpler “building-block” molecules.

Astronomers suspect that comets preserve material from the ancient cloud of gas and dust that formed the solar system. Exploding stars (supernovae) and the winds from red giant stars near the end of their lives produce vast clouds of gas and dust. Solar systems are born when shock waves from stellar winds and other nearby supernovae compress and concentrate a cloud of ejected stellar material until dense clumps of that cloud begin to collapse under their own gravity, forming a new generation of stars and planets.

These clouds contain a wealth of materials. Carbon dioxide, water, and other gases form a layer of frost on the surface of these grains of dust. Radiation in space powers chemical reactions in this frost layer to produce complex organic molecules. The icy grains become incorporated into comets and asteroids, some of which impact young planets such as ancient Earth and deliver organic molecules.

“The next step is to see if the organic material being found in comets came from the primordial cloud that formed the solar system or if it was created later on, inside the protoplanetary disk that surrounded the young sun,” says Dominique Bockelée-Morvan from Paris Observatory.

This research was funded by NASA, and the findings were published October 23, 2015, in the journal Science Advances.

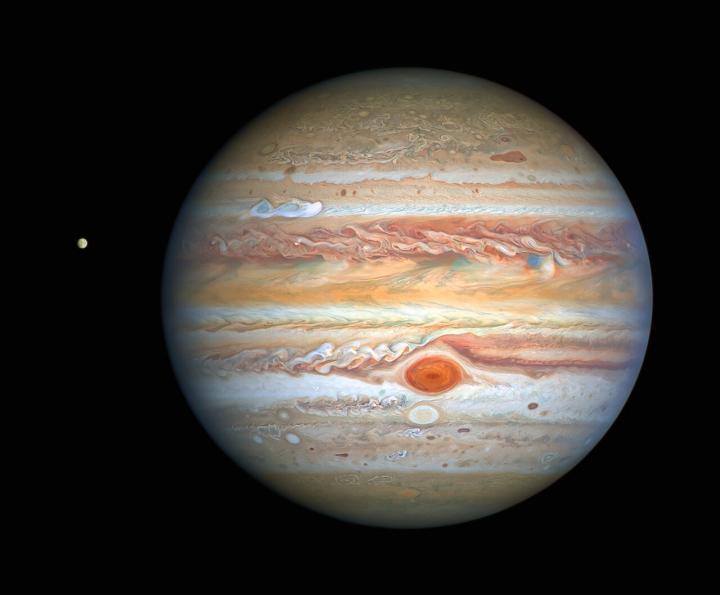

Top image courtesy of Fabrice Noel: Comet Lovejoy C/2014 Q2, photographed February 22, 2015.

Science Connected Magazine translates complex research findings into accessible insights on science, nature, and society. For more science news subscribe to our science newsletter!