Would you like to know how our brains process the information we need to catch or throw? A scientist explains how we learn to catch.

By Kate Stone

If you’ve ever played baseball or football and fumbled a catch, then wondered why, you are in the right place. A biologist has come up with a hypothesis of the way in which our brains learn to time a catch or a throw, and it has to do with how our brains process temporal information.

Daya Gupta, biologist and professor at Camden County College, USA, used to fumble the ball on the cricket field as a kid, so he turned his fumbles into answers. Now, with input from 60 researchers worldwide, Gupta explains how we learn to catch, hit, and throw.

RELATED: BETTER UNDERSTANDING THE HUMAN GRIP

How Fast is that Ball Moving?

Whether it’s making a catch, jumping over an obstacle, or avoiding a crash, humans need to react very quickly. When we are young, we are not very good at that. Whether we need to react in milliseconds or minutes, our brain gives commands to various parts of the body. The faster we need to perform the action, the faster the commands. But that is just the beginning.

We had the pleasure of asking Gupta about his research, which explains a learning process similar to the way we can learn to use tools, control prosthetics, or control robotics with our brains.

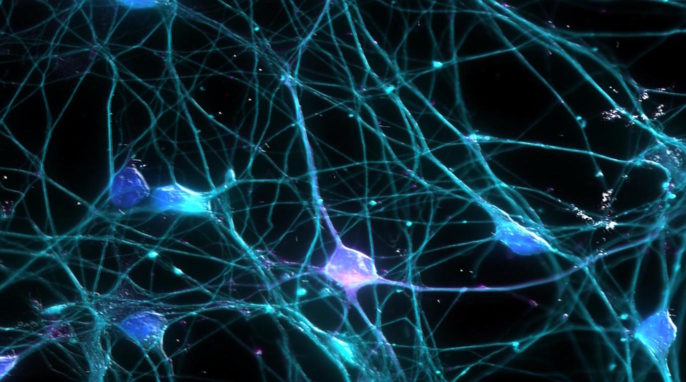

“When catching a ball we have to be accurate within a fraction of a second, and our body stores information to get that right,” Gupta says. When performing an action or seeing it performed, we can learn how long it takes and remember for next time. When our brain decides that we need to catch a ball, it acts on signal bursts coming from different parts of the brain – namely in the cerebellum and cortex. When we learn to catch, these signals give us the timing of the action.

The signals are generated by neuronal oscillators. These include different kinds of neurons. Some of their nerve endings act like hard drives for sensory stimuli, like catching a ball or watching someone catch a ball. These hard drives make it possible to start learning about the timing of an action even before we perform it.

For Gupta, it’s the downtime between these signal bursts that’s most interesting. “Time is represented between those spikes,” he explains.

The new theory, based on current research data, proposes that the brain uses multiple inbuilt modular clocks for interval timing. Interval timing is involved in various sports activities. In baseball or cricket, for example, interval timing enables us to hit a ball in flight and estimate when the ball and bat will connect.

Practice makes perfect, right? This research helps to explain why. The more we practice catching a ball, the better our brain becomes at matching our timing intervals with external events, and giving orders accordingly. Then we can fine-tune our timing information to perform better next time.

We can also apply what we’ve learned to other physical tasks. For example, catching a ball and dodging a ball require the same understanding of how fast it’s approaching. That means that with every new task we perform, we are not only learning and fine-tuning, we’re helping ourselves execute different tasks in the future, too.

Different calibration modules for our internal clocks seem to be involved in throwing a ball and hitting a ball. Therefore, it is not surprising that professional athletes tend to specialize. In the world of professional sports, all-rounders are rare.

Teaching Your Child to Throw and Catch

For the benefit of new parents and future athletes, we asked Gupta a few additional questions about how people learn to catch.

Science Connected: Based on your findings, what advice would you give to parents who are teaching their young children to catch a ball?

Gupta: When training to be a batsman, a different network in the brain may be involved in comparison to when training to be a bowler. Therefore, my advice to parents who are teaching their kids to catch a ball is to refrain from involving their kids in batting activities. Parents should not try to teach two different skills at the same time.

SC: What advice might you give a person who fumbled a catch in yesterday’s game and feels badly about it?

Gupta: My advice to a person who fumbled a catch in yesterday’s game is to try again. Or also to explore other roles in that sport, such as batting, as that young individual may have natural advantages for other roles in that sport.

This research is published in the journal Frontiers in Psychology. A related article was previously published at ResearchGate.

Photo courtesy of Steven Spence