These little animals kill by punching as hard and fast as a bullet from a gun. Find out why the little mantis shrimp is so tough.

By Kate Stone

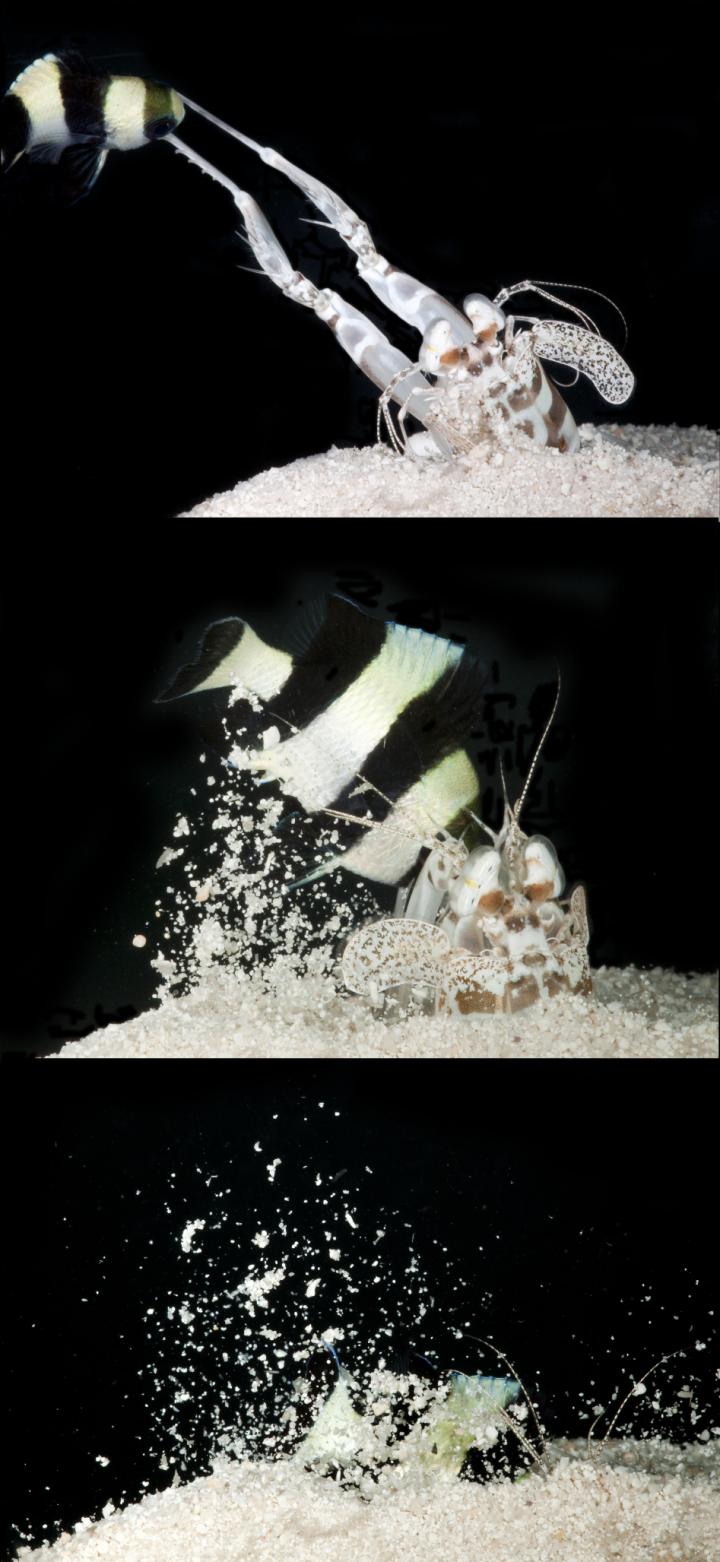

The miniweight boxing title of the animal world belongs to the mantis shrimp, a cigar-sized crustacean with front claws that can deliver an explosive 60-mile-per-hour punch. The speed of the shrimp’s strike has been compared to that of a bullet leaving the barrel of a gun.

A Duke University study of 80 million years of mantis shrimp evolution reveals how the little animal’s fast weapons developed a dizzying array of shapes — from spiny and barbed spears to hatchets and hammers — while still managing to pack a characteristic punch. “This research sheds new light on how these amazing movements evolved,” says Philip Anderson.

How Does the Mantis Shrimp Do It?

Anderson and fellow Duke researcher Sheila Patek have been studying 200 varieties representing 36 different species. What they found is that these powerful little animals use a system of biological springs, latches, and levers to power their fast punches, enabling them to strike much more swiftly than would be possible with muscle power alone.

RELATED: HOW DID SNAPPING SHRIMP EVOLVE THEIR SNAP?

Mantis shrimp, or stomatopods, are an ancient group of marine predators that are only distantly related to other crustaceans, such as crabs, shrimp and lobsters. They prefer to live in shallow tropical marine waters, but a few species are found in more temperate seas. Regardless of their common name, they are not actually shrimp nor mantids. Instead, they got their common name due to their resemblance to both praying mantis and shrimp.

The team took careful measurements and calculated each specimen’s ability to transmit force and motion to the part of the claw that swings out to smash or spear their prey — a mechanical property known as kinematic transmission.

When the researchers mapped their measurements onto the shrimp’s family tree, they discovered an evolutionary pattern called “mechanical sensitivity”. In the case of mantis shrimp, this pattern meant that certain parts of the claw were more strongly associated with changes in strike mechanics than others. Different varieties of mantis shrimp have been able to evolve different claws without any of them compromising their trademark punching power.

RELATED: Disco Clam, Colorful Mystery

The results of this study have been published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B. This research was supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation.

References

Anderson, P. S. L. and S. N. Patek. 2015. Mechanical sensitivity reveals evolutionary dynamics of mechanical systems. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 282: 20143088.

Patek, S.N., P. A. Green, M. V. Rosario. 2013. Internal Morphology. In: Treatise on Zoology – Anatomy, Taxonomy, Biology: the Crustacea. Vol. 4, Part A. Eds. J. C. von Vauple Klein, M. Charmantier-Daures, and F. Schram. Brill: Boston. pp. 202-216.

Patek, S.N., M.V. Rosario, J. R. A. Taylor. 2013. Comparative spring mechanics in mantis shrimp. Journal of Experimental Biology 216: 1317-1329.

deVries, M.S., E. A. K. Murphy, S. N. Patek. 2012. Sit-and-wait predation: behavior and biomechanics of the “spearing” mantis shrimp. Journal of Experimental Biology 215 (24): 4374-4384.

McHenry, M. J., T. Claverie, M. V. Rosario and S. N. Patek. 2012. Gearing for speed slows the predatory strike of a mantis shrimp. Journal of Experimental Biology: 215:1231-1245.