Many large mammals went extinct at the end of the last Ice Age (approx 11,000 years ago), including the Steppe bison, or Bison priscus. A team of scientists has found a complete specimen of this extinct bison frozen and naturally mummified in Eastern Siberia.

According to the research team, they have uncovered the most complete frozen mummy of the Steppe bison ever found. The frozen body has been dated to 9,300 years before the present day. It was found in the Yana-Indigirka Lowland and the team performed a necropsy to reveal how this animal lived and died at the end of the Ice Age.

The Yukagir bison mummy, as it is named, is one of only four preserved Steppe bison that have been found, and it may be the most intact. The animal has a complete brain, heart, blood vessels and digestive system, although some organs have shrunk significantly over time. The necropsy of this extinct bison mummy showed a relatively normal anatomy with no obvious cause of death. However, the lack of fat around abdomen of the animal suggests that the animal may have died from starvation.

Related: Do Mummies Decompose?

“The Yukagir bison mummy became the third find out of four now known complete mummies of this species discovered in the world, and one out of two adult specimens that are being kept preserved with internal organs and stored in frozen conditions,” explains Olga Potapova, a project scientist from the Mammoth Site of Hot Springs in South Dakota, USA.

Dr. Evgeny Maschenko from the Paleontological Institute in Moscow, Russia, adds, “The exclusively good preservation of the Yukagir bison mummy allows direct anatomical comparisons with modern species of Bison and cattle, as well as with extinct species of bison that were gone at the Pleistocene-Holocene boundary.”

Related: What was the wild ancestor of cattle?

Frozen extinct bison and mammoth mummies are changing the way we think about paleontology because of the large amount of information that can be ascertained from each specimen. With the organs, muscles, and other soft tissue preserved, these mummies are treasure troves of information. “The next steps to be done include further examination of the bison’s gross anatomy, and other detailed studies on its histology, parasites, and bones and teeth. We expect that the results of these studies will reveal not only the cause of death of this particular specimen, but also might shed light on the species behavior and causes of its extinction,” says Potapova.

This project is being led by Dr. Natalia Serduk of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow, Russia with contributions from scientists in Russia and the United States. Their findings are reported in the the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology (JVP).

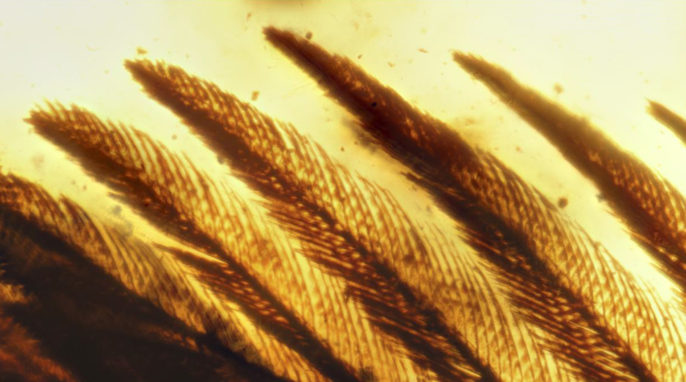

Image: A Steppe bison on display at the University of Alaska Museum of the North (Bernt Rostad of Oslo, Norway)