Two water weeds have an amazing ability to absorb oil from contaminated water. Is this a new means of cleaning up oil spills?

Oil—we use it every day, whether to power our cars or to heat our homes. Our appetite for crude oil continues to grow. This year the world is forecast to consume around 94 million barrels of oil per day (1 barrel = 159 liters or 42 gallons). Most of this oil is transported by sea, and with so much oil being transported, spillage is more likely. Not only are oil spills harmful to marine life, they are also expensive and difficult to clean up—sometimes taking years. Scientists in Germany have found that two floating aquatic weeds possess an amazing ability to absorb and retain oil from contaminated water and could be used as an environmentally friendly means of cleaning up oil spills.

Wonderful Weeds Are Cleaning Up Oil Spills

One method of cleaning up oil spills is by using selective sorbents. Selective sorbents are materials or mixtures of materials, either natural or synthetic, that selectively absorb oil from the water. Most natural sorbents, such as sawdust, wheat straw, and milkweed fibers, not only have a limited ability to absorb oil but also absorb water in the process. A good sorbent should repel water.

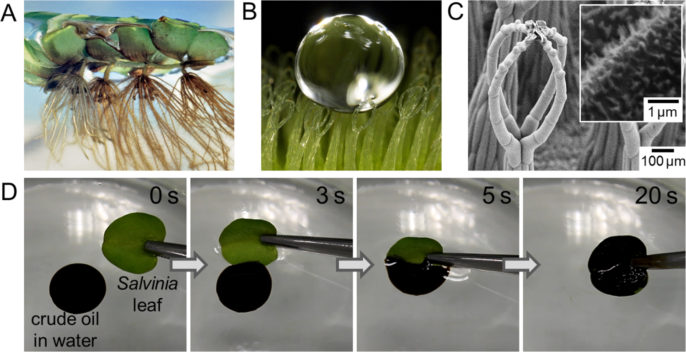

Previous studies explored the potential of the fern Salvinia molesta, considered one of the world’s worst aquatic pests: the plant can double in size in a couple of days under favorable conditions. Salvinia molesta and Pistia stratiotes, two aquatic floating ferns originating from South America, have been shown to have impressive water-repelling properties. In fact, scientists refer to them as superhydrophobic, meaning “super water hating.” These water-repelling properties are the result of two nanoscale leaf surface adaptations: tiny, hairy projections and a waxy layer of crystals coating them. The leaves are also able to trap a layer of air on their surfaces, so that they can float and survive even when they are submerged.

Scientists at the Institute of Microstructure Technology at Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) invented and patented a material called “nanofur” that mimics the dense hairs of Salvinia leaves. Nanofur can be produced by “pressing a hot, rough steel plate into a polymer foil. The surface of the polymer melts, and, when the steel plate is retracted, micro- and nanoscaled hairs are pulled from the surface,” explains Claudia Zeiger, PhD, researcher at the Institute and lead researcher for this study on Salvinia leaves.

Nanofur can selectively remove oil from water while repelling water. But Zeiger and her team wanted to further improve the oil absorption capacity of nanofur. Salvinia plants have been studied for their ability to remove heavy metals, such as lead, from wastewater. But as there was no information about the capacity of fresh Salvinia leaves to absorb oil, the team decided to find out for themselves.

Hairy Surfaces

Zeiger and her team studied the oil absorption capacity of fresh leaves of four species of Salvinia with different leaf surfaces, water lettuce (Pistia stratiotes), and lotus (Nelumbo nucifera). In addition, they tested the oil absorption capacity of dried leaves of Salvinia molesta, Pistia stratiotes, and Nelumbo nucifera and compared their absorption capacity to commercial, artificial oil sorbents such as nanofur.

Did you know that smartphone touchscreens can now detect contaminants in water samples?

“The oil absorption capacity of hairy Salvinia molesta and Pistia stratiotes leaves was much higher than we expected,” said Zeiger. They were comparable to the oil absorption capacity of artificial sorbents (nanofur, Deurex Pure, and Öl-Ex). Oils that were higher in viscosity and density were absorbed better by S. molesta leaves.

Watch the Salvinia leaf in action. Researchers simulated an oil spill, and a Salvinia molesta leaf took less than 30 seconds to absorb the oil. Video: Salvinia molesta leaf absorbing oil (by Claudia Zeiger / KIT).

Next, Zeiger’s team investigated the role of the tiny hairs, known as trichomes, sticking out of the surface of the leaves in repelling water and absorbing oil. The shape of the tips of the trichomes is different for each species. Lotus leaves lack hairs.

They found that the length of hairs influenced the oil absorption capacity of the leaves, with longer hairs showing a better ability to absorb oil. S. molesta leaves had the longest hairs. But the shape of the tips turned out to make a difference too. The hairs on the surface of S. molesta look like tiny egg beaters when zoomed in and have a three-level hierarchical structure. One reason for the high efficiency in oil absorption by S. molesta and S. oblongifolia is that the tips of the hairs are fused together, enabling them to hold more oil in the spaces between the hairs.

“The most important lesson we learned from our experiments is that hairy, absorbent materials are generally better than nonhairy,” said Zeiger. “From our results we now know that the shape of the hair ends is important in supporting the oil and air interface to ensure maximum oil absorption and retention capabilities.”

Both fresh and vacuum-dried leaves of Salvinia and Pistia absorbed more oil than Nelumbo nucifera leaves, which are nonhairy. But the dry Salvinia leaves were only water repellent on the top side because only the top surface of the leaf is hairy. In contrast, the dried leaves of Pistia were water repellent on both sides, because they are hairy on the top and bottom.

Using these findings, the researchers can improve the efficiency of nanofur in absorbing oil and repelling water. “For artificial, hairy oil sorbents, improved hair shape would be beneficial for oil absorption capacity,” said Zeiger.

Zeiger suggests that Salvinia molesta and Pistia stratiotes leaves are promising candidates for use as natural oil sorbents. “As they are pest plants in many regions of the world, using them as oil absorbers might potentially solve two problems at a time: removal of unwanted plants and production of natural and selective oil sorbent material at low cost.”

Reference

Claudia Zeiger et al. (2016). “Microstructures of superhydrophobic plant leaves – inspiration for efficient oil spill cleanup materials,” Bioinspiration & Biomimetics. DOI: 10.1088/1748-3190/11/5/056003.

Photo of Salvinia molesta by Eric Guinther.

About the Author

Neha Jain is a freelance science writer based in Hong Kong who has a passion for sharing science with everyone. She writes about biology, conservation, and sustainable living. She has worked in a cancer research lab and facilitated science learning among elementary school children through fun, hands-on experiments. Visit her blog Life Science Exploration to read more of her intriguing posts on unusual creatures and our shared habitat. Follow Neha on Twitter @lifesciexplore.