Long ago, snakes had legs, so how did snakes lose their legs? A fresh clue as to how and why has been found deep in an ancient snake’s inner ear.

By Kate Stone

Being legless is not what makes a snake a snake. As this article explains, it is the flexible, unhinged jaw that distinguishes a snake from a legless lizard. And yet, developing legs only to lose them may seem like evolution in reverse.

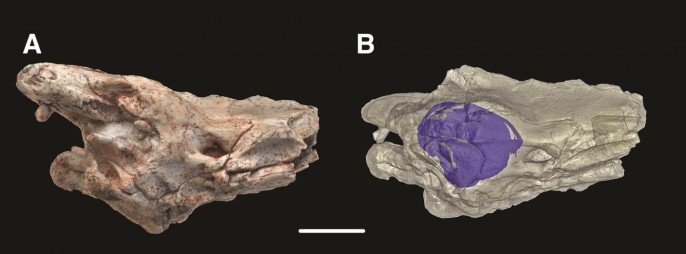

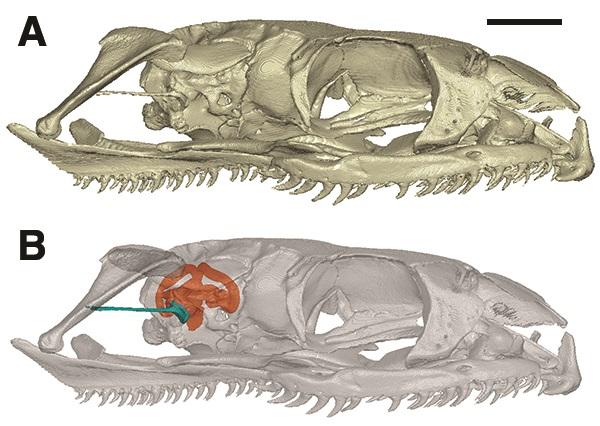

A 90 million-year-old snake skull is giving researchers vital clues about how snakes lost their legs as they evolved. Comparisons between CT scans of the fossil and modern reptiles suggest that snakes lost their legs when their ancestors evolved to live and hunt in burrows, habitats in which many snakes still live today.

The findings disprove previous theories that snakes lost their legs in order to live in water.

RELATED: MEET THESE 167 MILLION YEAR OLD SNAKES

Looking Deep Inside the Fossil

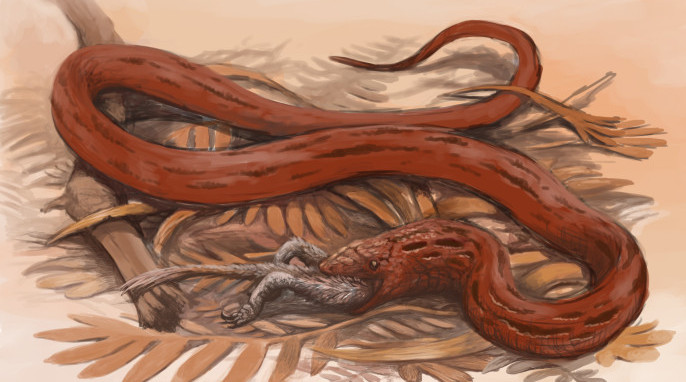

Scientists used CT scans to examine the bony inner ear of Dinilysia patagonica, a 2-metre long reptile closely linked to modern snakes. These tiny canals and cavities, like those deep inside the ears of modern burrowing snakes, controlled its hearing and balance.

According to Mark Norell of the American Museum of Natural History: “This discovery would not have been possible a decade ago. CT scanning has revolutionized how we can study ancient animals. We hope similar studies can shed light on the evolution of more species, including lizards, crocodiles, and turtles.”

Researchers compared the inner ears of the fossils with those of living reptiles. They found a distinctive structure within the inner ear of animals that actively burrow. This shape was not present in the modern snakes that don’t burrow underground.

The findings help scientists fill gaps in the story of snake evolution, and confirm Dinilysia patagonica as the largest burrowing snake ever known. They also offer clues about a hypothetical ancestral species from which all modern snakes descended, which was likely a burrower.

“How snakes lost their legs has long been a mystery to scientists, but it seems that this happened when their ancestors became adept at burrowing. The inner ears of fossils can reveal a remarkable amount of information, and are very useful when the exterior of fossils are too damaged or fragile to examine,” says Hongyu Yi, of the University of Edinburgh’s School of GeoSciences.

This research was funded by the Royal Society and published in the journal, Science Advances.

Artist’s conception of Dinilysia, shown here swallowing a baby dromaeosaur. Credit: Emily Willoughby