By Helen Petre

People drink alcohol to have fun, be social, feel less pain, and other reasons not usually related to nutrition. People make alcohol out of sugar and yeast, for these purposes. Fruit has lots of sugar. Ripe fruit starts to ferment when naturally occurring yeasts use the fruit for energy through fermentation. Fermenting fruit naturally produces ethanol (alcohol), as a product of fermentation. This occurs in the wild anywhere there is sugary fruit and yeast. So if alcohol is out there in the wild, are animals consuming alcohol with their fruit?

Ecologists from the UK, Canada, and US reviewed the evidence of animal alcohol consumption in nature and in lab experiments. They recently published their results in Trends in Ecology and Evolution. Although humans cannot accurately determine the inebriation state of an animal, they can measure behavior, preference, and expression of alcohol-metabolizing enzymes. The researchers argue that since ethanol (alcohol) is present in fruits, saps, and nectars, it is likely regularly consumed by animals that regularly consume sugary fruit, saps, and nectars.

How did alcohol evolve?

Since flowering plants started producing fruits and nectars around 100 million years ago, it is likely that yeast was fermenting sugar for millions of years and that animals were consuming alcohol with their fruit for millions of years. Humans may like the effects of alcohol consumption, but an animal trying to climb a tree, fly, or escape from predators is at a significant disadvantage. So how does this work? It seems like if animals were inebriated all the time, they would all die, or be eaten, and evolution would have removed them from the gene pool.

Since animals, and human animals, are still here, this did not occur. So what happened? How did the animals survive? The researchers show that animals, as well as humans, have varying expression of genes that metabolize, or break down, alcohol. Evolution being what evolution is, those animals able to break down the alcohol they consumed did not fall out of trees, or fly into solid objects, or get eaten by predators, as frequently as those animals with fewer metabolizing enzymes. The animals with more enzymes left more offspring, and somehow, they can use the calories in the fruit and alcohol to grow and reproduce more efficiently than those animals with fewer enzymes to break down the alcohol. The animals with fewer enzymes fell out of the trees and did not pass on their genes.

Ethanol in nature

In nature, ethanol is produced by yeast, and it is probable that yeast evolved the fermentation process in order to produce ethanol to protect itself from bacteria. Yeast can use the fermentation process in low-oxygen, high-sugar environments. Fermentation does not require oxygen and is less efficient at producing adenosine triphosphate (ATP). ATP is the universal energy molecule and the source of energy for all living things. Fermentation produces very little ATP and lots of alcohol, which is antibacterial. When the level of ethanol is high, or there is little remaining sugar, yeast use alcohol dehydrogenase enzymes to break down ethanol into acetaldehyde. Acetaldehyde is converted to acetate. Acetate then enters the mitochondria and starts what is called the Kreb cycle.

Humans and most animals use the Kreb cycle to make ATP. The Kreb cycle produces lots of ATP and no alcohol; this requires oxygen. In oxygen-poor environments, humans and most animals can use fermentation to make very little ATP and lactic acid. This is what your muscles do when they are very tired and out of oxygen. It is also why your muscles hurt the day after you do a lot of exercise. Lactic acid has to be converted back into other molecules that can enter the Kreb cycle and be used to make ATP with oxygen, later, when oxygen is available. Humans cannot use fermentation for very long. They must rely on oxygen and the Kreb cycle to produce enough ATP.

Yeast, bacteria, and other microorganisms use fermentation effectively. They survive nicely on the amount of ATP produced and do well without oxygen. The problem is that if ethanol builds up to high enough levels, it is toxic. So yeast has lots of alcohol dehydrogenase enzymes to break down alcohol and avoid death by alcohol overconsumption.

Humans and other animals have alcohol dehydrogenase enzymes in their livers. These enzymes break down alcohol. Some people and some animals produce more of these enzymes than others. Just like some people can drink large quantities of alcohol and not get very inebriated, some animals also have a lot of these enzymes and metabolize the alcohol better than other animals. The animals that can break down the alcohol stay alive and the animals that cannot break down the alcohol don’t.

How much ethanol is out there?

There are plants everywhere producing sugar-rich substrates for yeast fermentation. Even in temperate regions, ethanol is ubiquitous. In tropical regions, fermentation is a year-round process. The researchers found concentrations as high as 10 percent in overripe palm fruits. Even at lower percentages, animals eating significant quantities of fruit with 4 percent ethanol need a method to break down the alcohol.

RELATED: Making Antipsychotics with Baker’s Yeast

How common is alcohol consumption in nature?

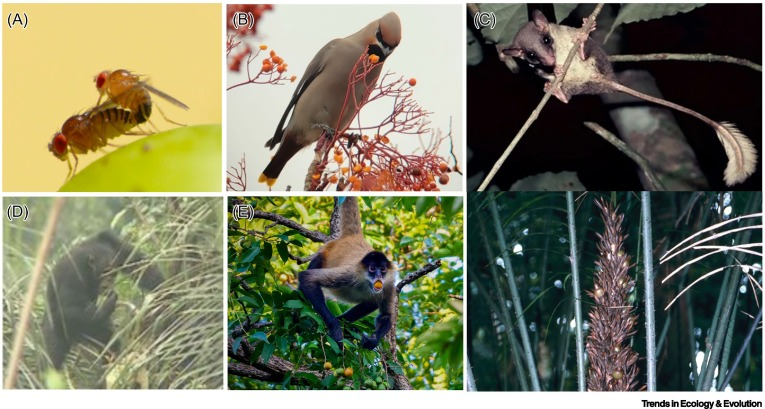

Animals that eat fruit, sap, or nectar routinely consume large quantities of alcohol. Drosophila melanogaster (fruit flies), those flies you studied in college biology labs, really like alcohol. In fact, they prefer fermenting fruits as a place to lay their eggs. In lab environments, the flies used substrate concentrations up to 15 percent. For reference, light beer contains two percent and distilled spirits contain 50 percent. Not surprisingly, fruit flies metabolize alcohol very efficiently. There are anecdotal accounts of wasps, butterflies, and honeybees consuming alcohol, which is most probably true because these insects are attracted to the sugar in cans and drinks at outdoor events and garbage cans. Everyone has seen bees hanging around garbage cans with sugary anything in them. There was even a lab study that found honeybees that search for nectar, preferred wine, and had higher levels of alcohol dehydrogenase enzymes than their sisters in the hive.

In my personal experience of insect trapping, I used alcohol traps for bark beetles. The lures were ethanol. They smelled like beer, or maybe stronger stuff. Ambrosia beetles and other insect pests are attracted to alcohol because it is indicative of stressed or weakened trees, which are good places for the beetles to make homes. We put ethanol traps out on or near trees to see if there were beetles around. Hopefully if there were, the beetles all went in the trap to drink the alcohol and died.

How about mammals? Are human mammals drinking alone? Nope. It is a veritable party out there. Elephants, baboons, and even a moose in Sweden found stuck in a tree (!) get drunk on fermented fruit rather frequently. In fact, mammals will take alcoholic beverages from humans. Tourists in St. Kitts have to hold onto their fruit cocktails, or the nonnative wild green monkeys will snatch them.

In lab experiments, hummingbirds, bats, slow lorises, hamsters, and aye ayes demonstrated preferences for ethanol up to 5 percent over non-ethanol food substrates.

How about DUIs in the wild? Cedar waxwings that ingested fermented berries, other birds, bats, and squirrels all have been reported flying into solid objects or falling out of trees. Waxwings who died by flying into solid objects had enlarged livers and high ethanol levels in their livers and intestinal tracts. Usually this behavior is discounted as accidental, but maybe not. Monkeys and chimps repeatedly consume fermented fruits and the chimps in Figure 1 were consuming palm sap that was collected by humans. They even made leaf sponge tools to collect the sap, when they could have more easily eaten other fruits.

Evolution of alcohol dehydrogenase

Alcohol consumption affects a wide range of metabolic enzymes and exposure increases metabolism. Flies that feed and breed on decaying fruits have more ethanol tolerance than those that do not. Honeybees that leave the hive have more ethanol tolerance than those that remain in the hive.

The evolution of alcohol dehydrogenase occurred about 10 million years ago, when African forests were replaced by savannah. Around this time, our ancestors became more terrestrial and were more likely to find fermenting fruit on the ground, instead of ripe fruit in the trees. If some individuals were more able to metabolize ethanol in this fruit and use it as a source of calories, those individuals would be healthier and pass their genes to offspring more frequently than those individuals with fewer genes to enable metabolism of ethanol. Those individuals with lower ability to metabolize ethanol would be sleeping or unable to respond to potential mates or predators and they would not be able to pass on their genes.

RELATED: Learn more about alcohol in nature with Comet Lovejoy Delivers Free Alcohol

This is also true in birds. Fruit-eating birds, such as waxwings, have more alcohol dehydrogenase expression than starlings and finches, which eat seeds. Aye ayes and slow lorises also have high levels of gene-regulated alcohol metabolism.

Treeshrews eat prodigious quantities of fermented palm nectar with high levels of ethanol, but show no signs of inebriation. ADH1 is the enzyme, expressed in the liver, that humans use to metabolize ethanol. We don’t exactly know how an inebriated treeshrew should act, but we do know that they have very high levels of ADH1 in their livers. In fact, it was four times higher than in humans, which would lead us to believe that treeshrews are very good at metabolizing ethanol and do not fall out of trees after alcohol consumption. This enzyme is variable in human populations and is very high in Han Chinese. In fact, it is so high that this population metabolizes ethanol so quickly that the acetaldehyde accumulates to toxic levels.

Reproductive choice

Ethanol has a cognitive influence on animal consumers. For example, D. melanogaster demonstrates reduced choosiness and copulates with more males following ethanol exposure. D. melanogaster males that are rejected by females consume alcohol after rejection. Sort of like the corner bar? Ethanol intake is associated with increased arousal, relaxed inhibitory control, and impaired cognitive ability. This is also supported by lab experiments with rodents. Seems like humans, flies, and rodents respond in a similar manner to ethanol.

It is possible that alcohol consumption increased social interactions and thus was actually beneficial to community building, social interactions, mating success, and relationship building, even as it decreased memory, pain, and anxiety, and increased risk-taking behavior. In certain environments, this could be beneficial, or not. A little bit could be successful. A lot could result in death. Most medicines are like that too. Most spices are too. A little is good. A cup full of cinnamon is very bad.

Concluding thoughts

As ethanol is present in most sugary foods, it is probable that humans are not drinking alone, and alcohol consumption is not as rare in nature as we thought. If fruit flies are doing it, well, other animals are too. Evolution has a way of making what is there work really well for those who can use it. While too much alcohol is probably really bad in the wild, so is too much of just about everything else, including water, and food of any kind. Animals that consume large quantities of fruit, including humans, have evolved genes to metabolize the ethanol produced through fermentation, using it for calories (whether we need them or not) and sometimes nutrition. The researchers remind us that we are a part of an ecosystem that evolved to live on Earth. We are more like other animals than different, or special. We are all here because we evolved to have the genes we need to use the products that are here. We are not the only animals that use alcohol.

This study was published in the peer-reviewed journal Trends in Ecology and Evolution.

Reference

Bowland, A., et al. (2024). The evolutionary ecology of ethanol. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2024.09.005.

About the Author

Helen Petre is a retired biologist who continues to learn and teach science. She spends lots of time volunteering at Emerald Coast Adventures, working at Bass Pro, and taking her grandson to story hour at the library.