Renowned paleontologist Dr. Dave Hone explains how the largest mounted dinosaur skeleton in the world was put together. Photography by Steven Spence.

By David Hone

Dr. Dave Hone is a lecturer at Queen Mary, University of London, specialising in dinosaurs and pterosaurs. In addition to writing for The Guardian, he blogs at Archosaur Musings, is a contributor to Pterosaur.net, created Ask A Biologist, and has published more than 50 academic papers on dinosaur biology. His latest book, The Tyrannosaur Chronicles, is now available from Bloomsbury Publishing.

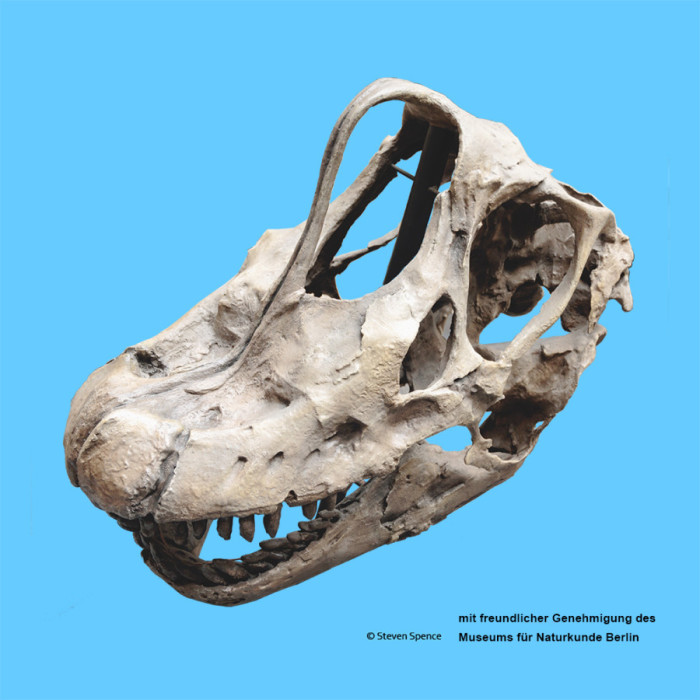

Few visitors to the Museum for Nature in Berlin can fail to be impressed by the truly colossal dinosaur that takes centre stage in the main gallery. Standing around 13 m tall and over 20 m long, the giant sauropod Girafatitan (formerly called Brachiosaurus) from the Late Jurassic of Tanzania is one of the largest dinosaurs on exhibit anywhere in the world. What is more impressive is that unlike many other huge mounts (and many dinosaur skeletons on display, generally) much of this is made up of the original fossil bones.

For a number of reasons, many dinosaurs on show in museums are casts of skeletons, rather than the original fossils themselves. There are certainly not enough Tyrannosaurus skeletons to go round, so museums make copies to go on display, but there are other considerations too. Mounting a skeleton can put it at huge risk – fossils are fragile, and even the act of putting them on show can damage them — and years of exposure to lights (artificial and natural), changing humidity, and the public themselves can cause serious damage to specimens that in some cases are the only known examples of a given species.

Even when a real specimen is mounted, it is rarely complete. There are only a handful of dinosaur skeletons out there for which every single tiny bone, down to the tip of the tail, is known. As a result, gaps need to be filled in and this can be done through a number of methods. The first option is to take a real bone, or a copy of one, from a different specimen of the same species (or a close relative) that has the bone you need. Alternatively, you could duplicate something you already have to fill a gap (one rib often is much like another, for example). Finally, you can make a sculpture – have someone sit down a craft something to look like the bone you need, based on what is known about it. Similar techniques are also used to complete broken or damaged bones in order to produce a whole.

RELATED: SAUROPOD DIETS AT THE JURASSIC DINNER TABLE

Some museums make any sculpted or duplicated elements a contrasting colour to show what restorative work has been done, while others try to disguise the work these joins as a way to help best show off the specimens and given an appreciation of how the skeleton would have really looked. With a practiced eye though, it is generally not hard to tell one from the other. Bones do look different, even from high quality casts, and sculptures tend to be very smooth and lack fine details.

The Berlin Giraffatitan combines all of these effects. The mounted skeleton is a composite of the fossil bones of several different animals (as none of the skeletons were especially complete) and also includes casts of bones and sculpted pieces. The whole exhibit is stunning, but still more impressive is the fact that this specimen was first mounted in the 1930s, which must have been a tremendous technical challenge. Methods for mounting skeletons have certainly changed and improved in the intervening years. Greater consideration is now given to the bones themselves and the science that involves them.

Even many large bones, like those of the legs, are quite fragile. These are fossils, so while they have the shape of the bones of long-gone animals, they no longer have the material properties of bones, but the rocks that they have become. This often makes them brittle, and some bones can’t even hold their own shape without support. In the case of the original mount, the long bones literally had holes drilled through them and metal beams inserted. This did mean that the bones were well supported and the mounted skeleton was not covered in a mass of metal struts, but also it meant doing real and irreversible damage to the bones themselves (science was not always the priority).

Modern Dinosaur Mounting

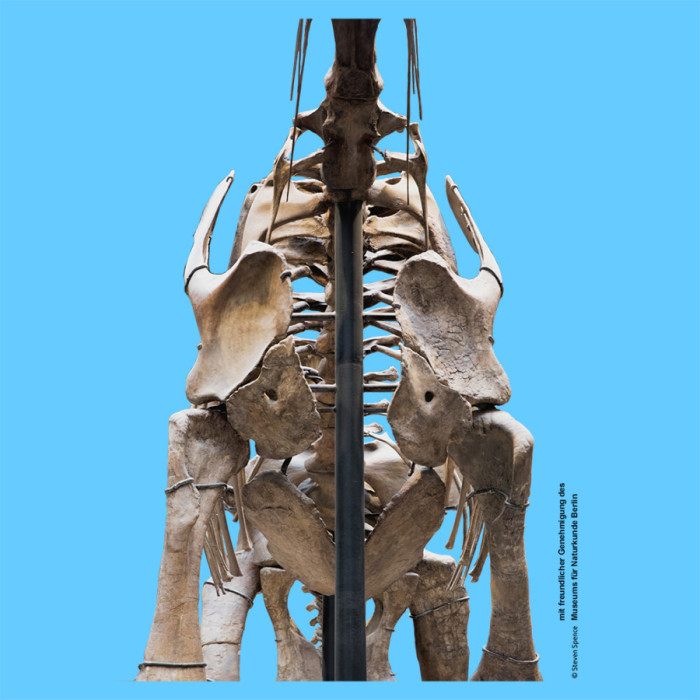

However, things today are not as they once were. Over the course of several years, finishing in 2007, the mounted skeleton was disassembled, cleaned, repaired, and remounted. In addition to giving the whole thing a once over and scanning critical bones for research, this was also an opportunity to update the posture of the animal. The skeleton was put in a new pose, reflecting some 75 years of research. The tail, for example, was put to a more horizontal position and no longer near dragged on the ground. New casts and sculpted elements were put in to improve the specimen, but most importantly the way the skeleton was mounted changed.

No longer did giant poles pierce the bones, but instead the whole skeleton was supported by an external metal framework. A huge number of cradles were put in place, with each holding a single bone in place and bolted to the central frame. The cradles were individually cut and welded so that they fitted onto each bone to support it without damaging it. This is better for the bones, but also those who work on or with the remains, because individual bones can now be easily removed for cleaning and repair, or examination by scientists.

The main difference in fossil mounting technique in the twenty-first century is that, although these exhibitions are still spectacular, every care for the fossils themselves (both in the short and long term) take priority. This is very welcome from the perspective of researchers, but it also bodes well for the public because fossils will be on display for longer and changes will be easier to make to mounts as single bones can be removed or replaced with ease.

This new system of mounting is becoming the norm, but with the limited budgets available, it’s largely limited to newly mounted fossil specimens. Still, it is increasingly common with museums working to ensure the best care of their dinosaurs while also maximising the access to them for scientists and the public. It’s certainly a welcome addition to the modern methods of creating dynamic and exciting museum exhibitions.

Featured photo shows the huge, mounted Giraffatitan in the main hall in Berlin, dwarfing the Diplodocus that stands behind it.