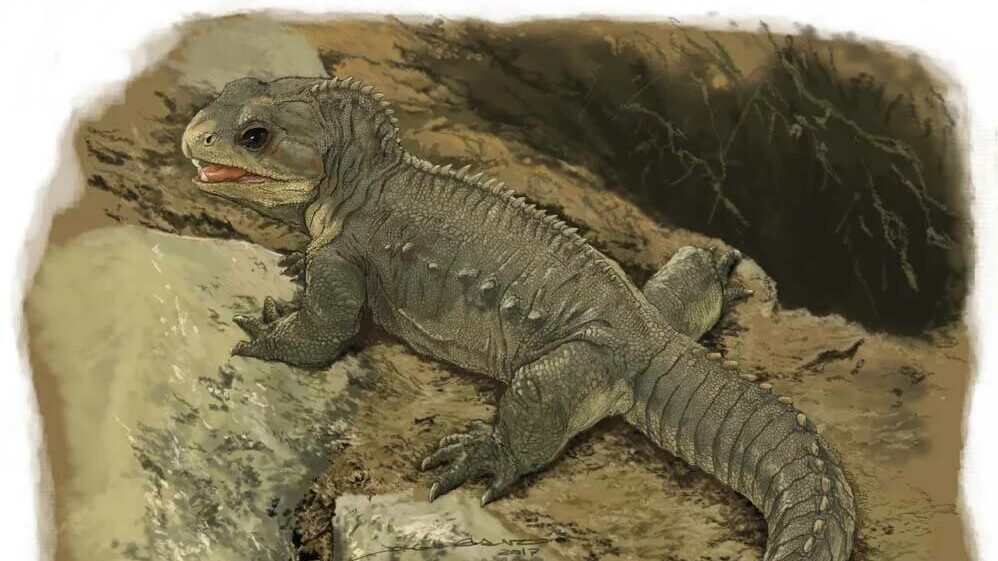

A Clevosaurus hadroprodon fossil, recently discovered in Brazil, is the oldest known sphenodontian from Gondwana, the ancient supercontinent.

By Jacqueline Mattos

A new reptile fossil was recently discovered in Brazil, in the southern state of Rio Grande do Sul. The research was published in the journal Scientific Reports and describes the species Clevosaurus hadroprodon, which has turned out to be the oldest fossil of its kind from what was formerly Gondwana—the ancient supercontinent that split up into Africa, South America, Australia, Antarctica, the Indian subcontinent, and the Arabian Peninsula. The remains of the fossil, consisting mostly of the mandible and skull bones, were found in rocks that date back to the late Triassic period, from approximately 237 to 228 million years ago.

The Triassic marked the transition after the great mass extinction in the Permian and is described as a period of great diversification of life, for both terrestrial and marine vertebrates. During the Mesozoic era, also known as the “Age of Dinosaurs,” the rhyncocephalians (the sister group to the squamates, which include modern lizards and snakes) were widespread and diverse. Currently, however, rhynchocephalians—which include sphenodontians—are represented by only one living species in New Zealand (Sphenodon punctatus), while lepidosaurs in general comprise more than 10,000 species. The Clevosauridae group, which represents a well-known early sphenodontian clade, now has many species distributed in three main genera: Brachyrhinodon, Clevosaurus, and Polysphenodon, with Clevosaurus being the one with the highest number of known species (six) and the most widely distributed.

RELATED: EXTINCT BISON FOUND FROZEN IN SIBERIA

Big first tooth

The inclusion of Clevosaurus hadroprodon in the order Sphenodontia is supported by many features, such as teeth that are firmly rooted in the upper and lower jaws. Other features such as the possession of a large, tusk-like tooth in both premaxilla in the first tooth position can be considered a differential feature for this species, differing from all other known sphenodontians. The species name hadroprodon was given in reference to the phrase “big first tooth” and comes from the Greek hadros (meaning “large”), protos (“first”) and odous (“tooth”).

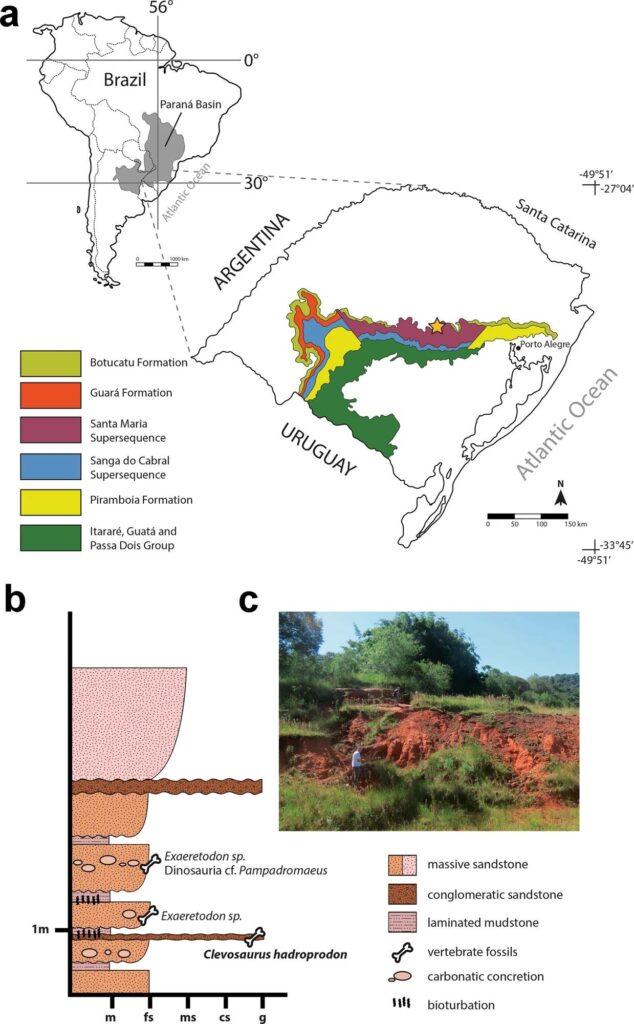

This fossil was found in the municipality of Candelária, in the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul, in the Paraná Basin. The remains were recovered in Linha Bernardino outcrop, a Triassic exposure with a depth of about six meters. The spot where the fossil remains of Clevosaurus hadroprodon were embedded is mostly composed of fine-grained to medium-grained sandstone, layered with mudstone, conglomerates, and carbonate concretions. Representatives of other taxa were also found in the same outcrop, mainly in the fine sandstone levels. Those included Exaeretodon riograndensis, Trucidocynodon sp., and other bones associated with a dinosaur fossil.

RELATED: VADASAURUS FOSSIL SHOWS A REPTILE IN TRANSITION

When comparing Clevosaurus hadroprodon with other sphenodontians or rhynchocephalians, there are a few features that stand out. This newly discovered species was placed in this clade mainly because of the way its jaw was constructed, but some of its features occur in other clades as well, such as the acrodontan squamates. However, the combination of characteristics seen in Clevosaurus hadroprodon has not been seen in other groups besides the sphenodontians.

According to Silvio Onary, a researcher from University of São Paulo and one of the scientists responsible for these findings, “the discovery of Clevosaurus hadroprodon is remarkably different from the others in the sense that it was a very old species (circa 237–228 million years old) possessing a mix of primitive and derived dental morphology. The species combines a tooth row similar to the primitive sphenodontians, associated with the derived feature of later species such as the procumbent modified massive tusk-like tooth in the premaxilla and dentary, a distinctive feature that is easily observed at first sight on that small fossil.”

A very special sphenodontian

But how does Clevosaurus hadroprodon differ from other sphenodontians? Researchers have shown that it lacks wear on the teeth, leading to the thought that this species probably had a different way of eating than chewing on its food (which was common in sphenodontians). Instead, it probably ate a lot of insects and spiders and used the tusk-like tooth to subdue prey. Its teeth are also different: they present a straight, blunt configuration, while in other sphenodontian species they can be more pointed and sharp. One of the possible explanations is that this set of teeth could be used not only for feeding but also in other behaviors, for example, in competition and defense.

Related: Prehistoric Crocodiles Ruled Ancient Peru

One of the most striking aspects of this discovery is that Clevosaurus hadroprodon is the oldest sphenodontian from Gondwana. The next oldest two on record are the Brazilian Clevosaurus brasiliensis and an Argentinean specimen of Sphenotitan leyesi. Onary tells Science Connected about the team’s research:

“Triassic fossils of lepidosaurs are somewhat scarce. The unveiling of Clevosaurus hadroprodon was groundbreaking in the sense that this reptile is the direct evidence of the oldest representative of its kind in the supercontinent Gondwana, representing the first record of a sphenodontian having the fully acrodont condition (the dentition fused to the top of the jaw bone). Additionally, this fossil reinforces the importance of Southern Brazil as a crucial fossiliferous locality for the prospection and study of fossils that may help to understand not only the rise of dinosaurs (which the territory is famous for) but also the early evolution of lepidosaurs reptiles.”

This study was published in the peer-reviewed journal Scientific Reports.

Reference

Hsiou, A. S., Nydam, R. L., Simões, T. R., Pretto, F. A., Onary, S., Martinelli, A. G., … Caldwell, M. (2019). A new Clevosaurid from the Triassic (Carnian) of Brazil and the rise of Sphenodontians in Gondwana. Scientific Reports, 9(1). doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-48297-9