By Kate S.

How many passwords do you keep track of? How many have you forgotten? According to researchers from Binghamton University, remembering lots of complicated codes may one day be a thing of the past. The unique way your brain responds to certain words could be used to replace passwords.

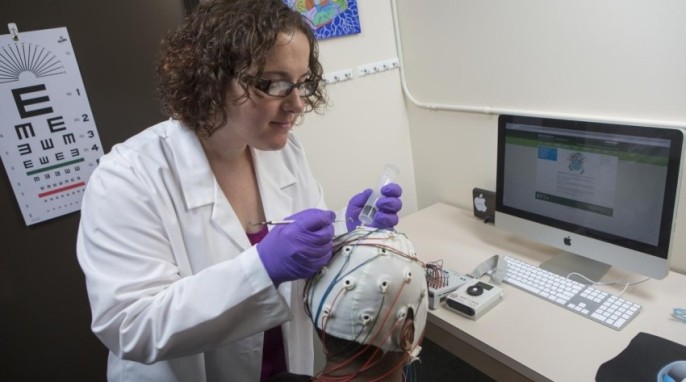

Studying Brain Biometrics

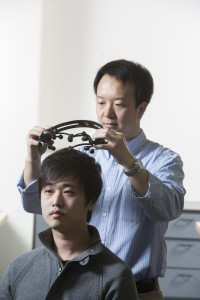

The research team monitored the brain signals of 45 volunteers as they read a list of 75 acronyms, such as FBI and DVD. They recorded the brain’s reaction to each group of letters, focusing on the part of the brain associated with reading and recognizing words, and found that participants’ brains reacted differently to each acronym. In fact, the difference was such that a computer system was able to identify each volunteer with 94 percent accuracy. The results suggest that brain waves could be used by security systems to verify a person’s identity.

Brainprints Trump Fingerprints

According to Sarah Laszlo of Binghamton University, brain biometrics are appealing because they cannot be copied the way a fingerprint or retina scan could. While fingerprints are fixed, brain biometric identification can be ‘reset’ by the individual by simply choosing a different acronym or word.

“If someone’s fingerprint is stolen, that person can’t just grow a new finger to replace the compromised fingerprint — the fingerprint for that person is compromised forever. Fingerprints are ‘non-cancellable.’ Brainprints, on the other hand, are potentially cancellable. That means that if someone was able to steal a brainprint from an authorized user, the authorized user could then ‘reset’ their brainprint,” Laszio explains.

Talking with the Scientists

We recently asked Laszio about her futuristic ID research.

GotScience.Org: So, what would it mean to “reset” a brainprint?

Dr. Laszio: We have shown that we can get very high biometric identification accuracy with a variety of different types of stimulation. We can certainly get high identification accuracy with words, but we have more recently discovered that we can also get high identification accuracy with other types of images, like pictures of faces or foods. So, one way to “reset” the brainprint would be to change the trigger from, say, a word to a picture or pictures of a face.

GotScience.Org: Will the system need to be more than 94% accurate?

Dr. Laszio: Yes, it definitely would be! In follow up work, conducted by our graduate student, Maria Ruiz-Blondet, we have been able to achieve 100% identification accuracy, at least in a small pool of laboratory subjects. That work has not been published yet, so it has not passed peer-review, but we are very optimistic about it.

Zhanpeng Jin, professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering, and Biomedical Engineering, doesn’t think that the brainprint is a system that will be mass-produced for everyday applications, at least not anytime soon. However, it could have security applications in high-stakes situations.

“We tend to see the applications of this system as being more along the lines of high-security physical locations, like the Pentagon or Air Force Labs, where there aren’t that many users that are authorized to enter, and those users don’t need to constantly be authorizing the way that a consumer might need to authorize into their phone or computer,” Jin says.

This research is funded by the National Science Foundation and Binghamton University’s Interdisciplinary Collaboration Grants (ICG) Program. The results are published In “Brainprint,” a study in the academic journal Neurocomputing.

Top Image: Sarah Laszlo, an assistant professor of Psychology, in her laboratory (Jonathan Cohen, Binghamton University photographer)

GotScience.Org translates complex research findings into accessible insights on science, nature, and society. For weekly science news, subscribe to our science newsletter!