Increasing amounts of plastic in our brains has scientists questioning how microplastics impact cognitive health.

By Helen Petre

Microplastics and nanoplastics (MNP), tiny pieces of plastic between 500 micrometers and one nanometer, are all over the Earth, and in our bodies, even though we can’t see them. We use lots of plastic. Then we throw it out, or recycle it, but tiny particles stay in our environments and in our bodies. We can’t see these tiny pieces, but they are there. Is plastic in our brains harming us? We have no idea.

Researchers at the University of New Mexico (UNM) used human tissue derived from autopsies done between 1997 and 2024 to determine the amount of MNP in the brains, livers, and kidneys of the deceased persons. They found that brains had more plastics than the other tissues. In addition, the amount of plastic in all tissues increased over time, so people who died in 1997 had less plastic in their organs than people who died in 2024. They also found that people with dementia had more plastic in their brains than people who died without being diagnosed with dementia.

Where does plastic come from?

We all use plastic, all the time, every day. We even wear plastic clothes. Where does it come from? It is just there, cheap, and easy to get. Plastic comes from natural gas and crude oil. It comes from fossil fuels. Crude oil is pumped out of the ground, transported to refineries, and heated, where it separates into different “fractions,” such as ethane, propane, and, the important fraction for making plastics, naphtha. Naphtha is made into ethylene and propylene, which is made into plastics.

RELATED: Reformulate, Reshape, Recycle! The Future of How to Make Plastic

How did we get plastic in our brains?

We really don’t know how plastic gets in our bodies, or how it gets in our brains, but we have some good ideas how it could happen. People eat plastic, along with their food, or inhale it, along with air. These tiny particles are absorbed into the blood and travel around the body. They enter organs and for some reason, stay there. It could be that they are just really tiny things and get stuck somewhere, but it is hard to get anything into the brain. The brain has a blood–brain barrier that works really well. It prevents things like bacteria and viruses and even antibiotics and other drugs from getting to the brain. We don’t have any idea how we get plastic in our brains, but we do.

Dr. Campen and his team at UNM used brain tissue from the frontal cortex, the largest part of the human brain, and the part that makes us human. The frontal cortex is responsible for reasoning, social understanding, working memory, and personality. Accumulating a whole lot of anything besides the brain in this area is probably bad (the effects are not yet known). They found quite a bit of plastic, relatively speaking, in the frontal cortex of all the brains they studied.

RELATED: Feeling Brain Fog? It Could Be in Your Blood

Polyethylene, polypropylene, polyvinyl chloride, and styrene-butadiene rubber

The most abundant plastic the UNM team found in the frontal cortex is polyethylene (PE). In fact, 90 percent of the plastic in our brains is PE, polypropylene (PP), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and styrene-butadiene rubber (SBR). PE is the most commonly produced plastic on Earth. It is used in plastic bags, bottles, food containers, and cups. One hundred million tons are produced (and mostly thrown out) annually. PE is made out of carbon and hydrogen, the same things we are made out of. PE is clear.

Polypropylene (PP) is the second most commonly used plastic. It is like PE but stronger and harder. PP is resistant to fatigue, so it is used in flip top bottles, Tic Tac boxes, and reusable plastic containers, like Rubbermaid. It is also used in plastic chairs, disposable bottles, plastic pails, car batteries, pitchers, and even carpets, rugs, and door mats. Interestingly 50 percent of the PP that is made is used in diapers and sanitary products.

Then, there are clothes. Look at the labels on your clothes, because they are actually plastic. PP is made into long underwear and shirts, and warm weather clothes, because it transports sweat away from the skin. The military has switched from PP to polyester because PP melts, which is not pleasant in some military applications, and PP also holds odors. Polyester doesn’t.

Polyvinyl chloride is the world’s third most commonly produced plastic. It is used to make raincoats and building materials. It is also used for bottles, credit cards, and inflatables. It is white and solid. Most PVC is made in China. There are lots of environmental issues with this product, but we still use it and it still ends up as one of the types of plastic in our brains.

Styrene butadiene is abrasion resistant and used in car tires, seals, chewing gum, latex gloves, and gaskets. It is a synthetic replacement for natural rubber. There is a whole lot of this on roads and airport runways. Even though it is abrasion resistant, tires take a lot of abuse.

All these things are everywhere. We use them. They break down and tiny pieces end up in us, even in our frontal lobes, which is most likely not good (more research is needed to know for sure).

Plastics in human tissues

Dr. Campen and his team used pyrolysis gas chromatography mass spectrometry (Py-GC/MS) to identify plastics and electron microscopes to see the tiny plastic pieces in the brain, kidney, and liver. They found the amount of plastics increased over time and they found more plastic in the brain than in the liver or kidneys.

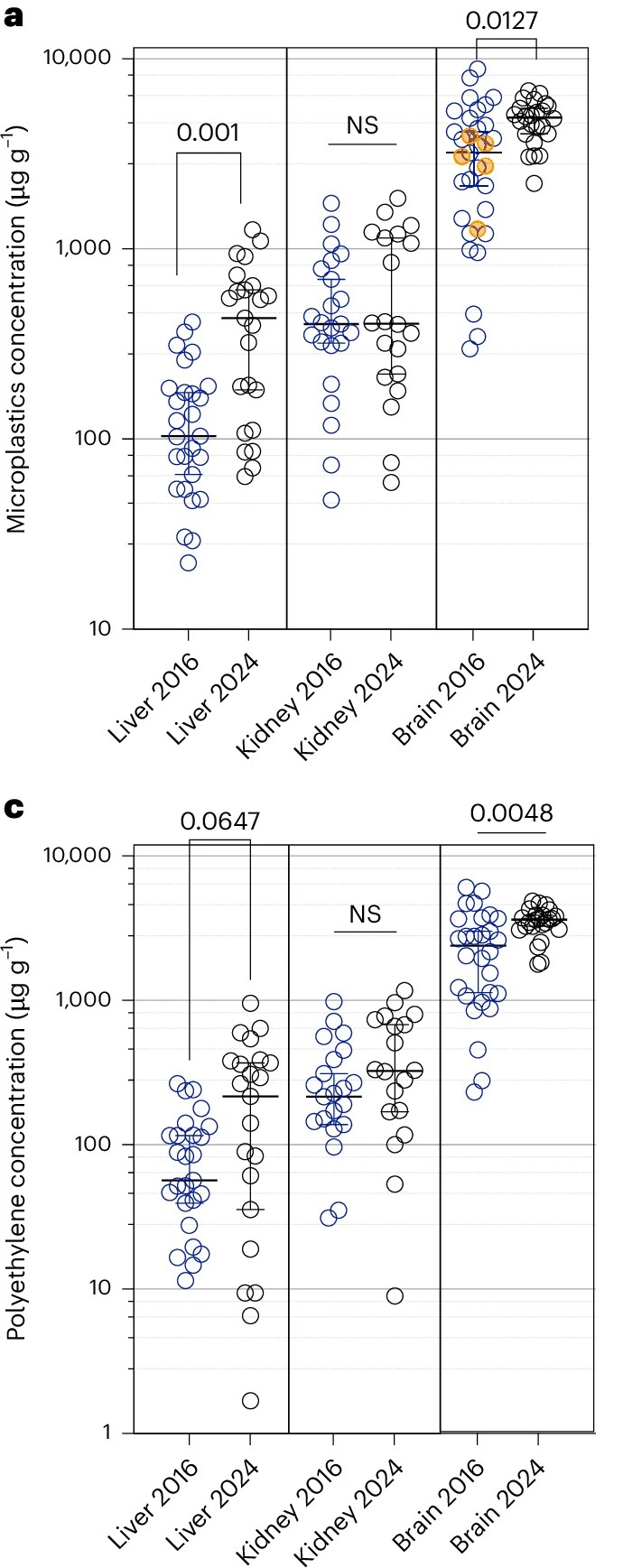

Figure 1 below clearly shows the brain has more MNP and more PE than other organs and the amount of MNP and PE has increased over time. This could be a result of humans just using more plastic in 2024 than in 2016, or it could be that we are keeping more of it in our bodies. The researchers did not find a difference in the amount of MNP in older deceased individuals than younger deceased individuals. They found more plastic in the brains of people who died in 2024, than those who died in 2016, which probably means that we are just using more and there is more in our environments.

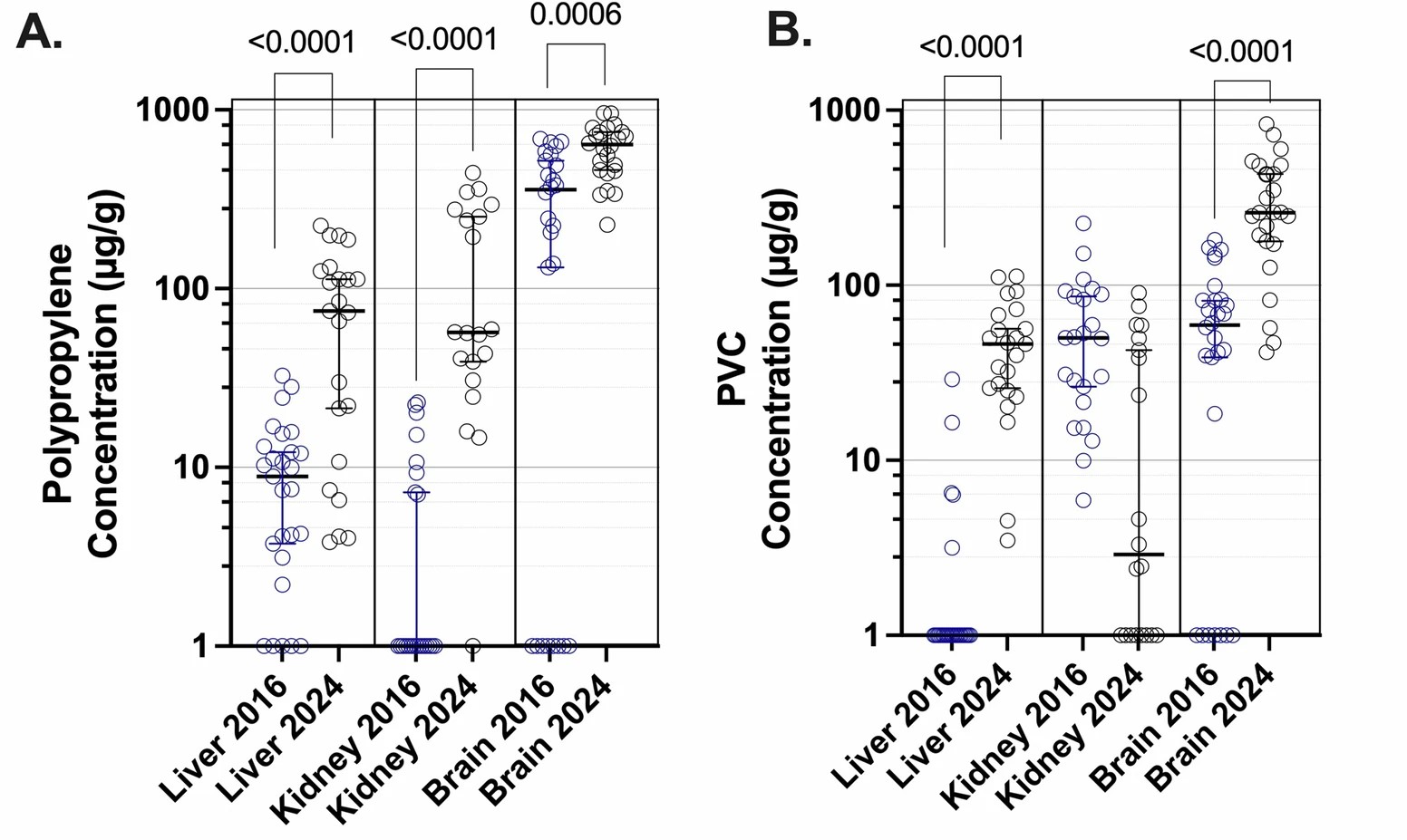

Figure 2 below shows similar results for PP and PVC. There is more PP and PVC in the brain than other organs and there is more PP and PVC in organs of deceased people in 2024 than in 2016.

Does all this plastic in our brains hurt us?

How does all this plastic in our brains and our organs affect us? We don’t know. The research team found that people who died with diagnosed dementia had more plastics in their brains than other deceased persons, however this is a correlation, not a cause. It may be that people with dementia have other issues that cause their brains to allow more plastic through the blood–brain barrier, so the extra plastic is not the cause of the dementia but the result.

It is suggested that MNPs are a threat to human health because of their small size and the fact that they are everywhere in our world. Billions of tons of plastic are produced each year and most ends up in landfills, or just everywhere. There has been an enormous increase in the use of personal protective equipment and an enormous increase in waste. We used masks, gloves, and all kinds of plastic things to prevent transmission of virus particles, but at the same time, we increased our exposure to potential plastic ingestion.

While the researchers do not know what the long-term effects of MNPs in human brains are, they clearly show MNPs are in our brains. Currently most humans shrug this off as science that doesn’t affect them. People don’t see it as any more than trash or containers laying around the beach. They don’t actually think about plastic being inside their bodies, and especially not in our brains. People have a hard time acknowledging things they can’t see, or things that aren’t hurting them or making them sick right now. Maybe we should try to learn about this before it hurts us.

There are many historical stories of things we thought were OK, that ended up being not OK. We thought smoking was cool. Wrong. We thought DDT was safe. Wrong. At least this time we can’t say we think it is OK. As Dr. Campen says, “I have yet to encounter a single human being who says, ‘There is a bunch of plastic in my brain and I’m totally cool with that.’”

This study was published in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Medicine.

RELATED: Plastic Pollution and the Recyclable Ruse

References

Nihart, A. J., Garcia, M. A., El Hayek, E., . . . & Campen, M. J. (2025). Bioaccumulation of microplastics in decedent human brains. Nature Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-03453-1

Figures 1 and 2 from research study were cropped from relevant sections of originals provided by Nihart et al. 2025 and licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

About the Author

Helen Petre is a retired biologist, striving to learn and share the excitement of learning with future generations.